Conditions

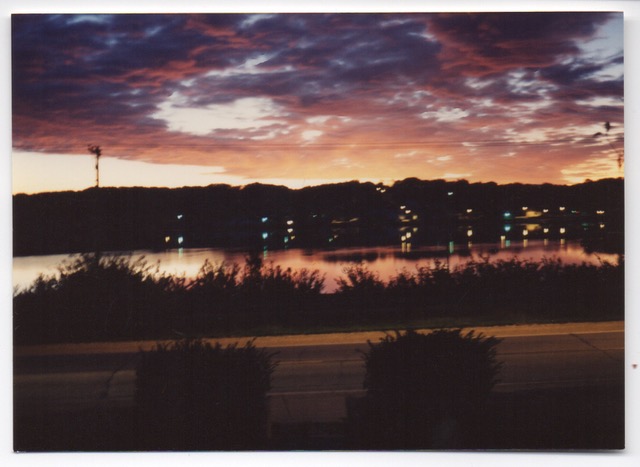

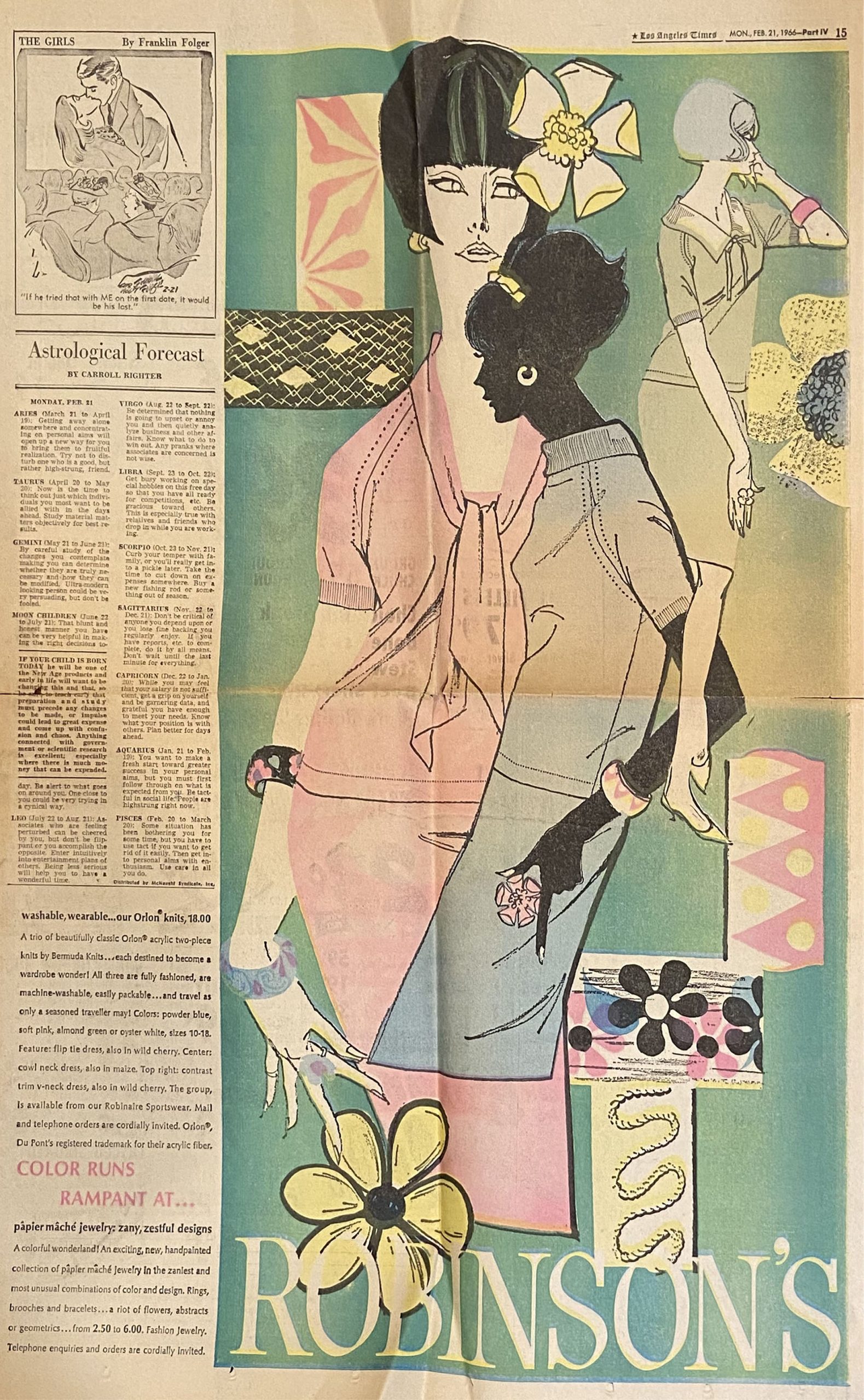

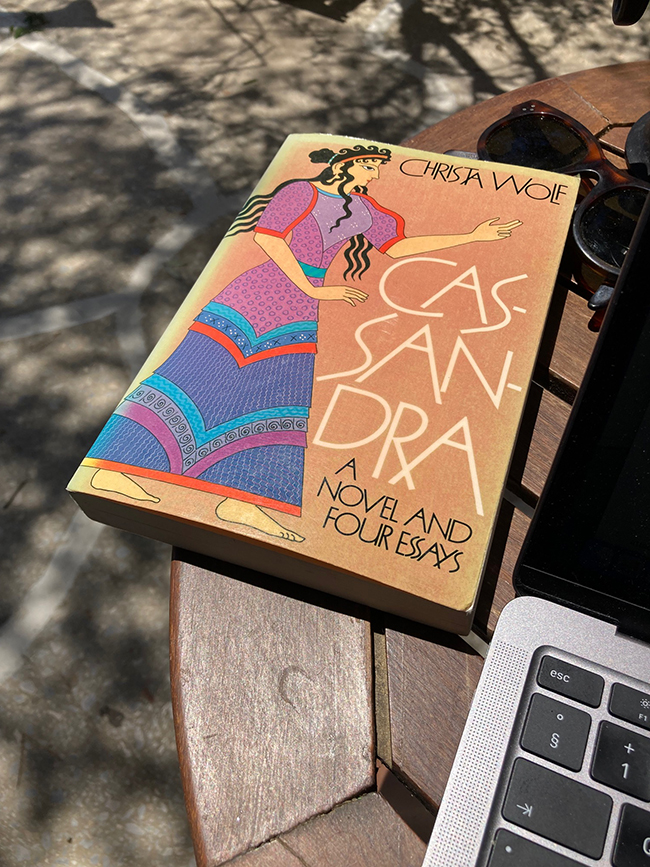

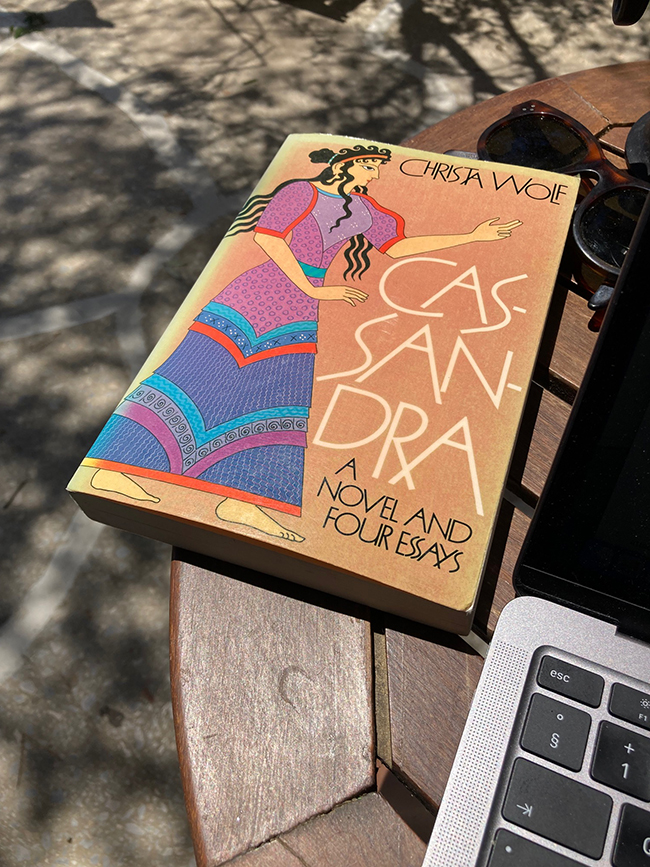

The wind was a seven or an eight—a hard seven he said. In our cabin on the rocking ship, throwing us back and forth, I tried to read the book I had brought, Christa Wolf’s Cassandra. The subtitle of the book was A Novel and Four Essays, but I was mostly taken with the title Wolf had given to the whole enterprise, which appeared on page 141: Conditions of a Narrative. I thought about the conditions of our current narrative—the long night boat to Anafi, the wild crossing of the windy Aegean, our ship stopping at a series of Cycladic islands until it would reach ours at dawn.

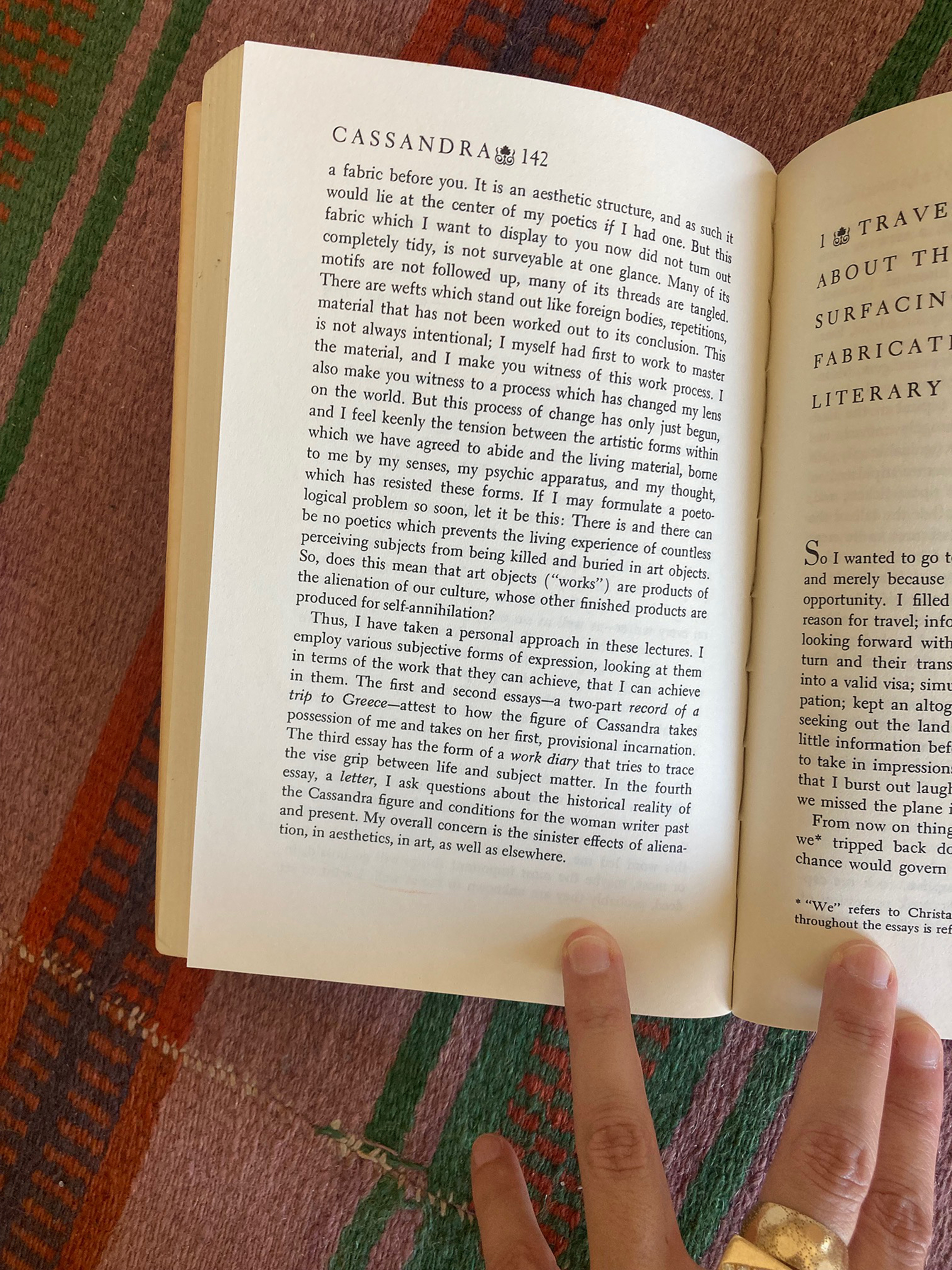

Page 141: “Ladies and gentlemen,” Wolf begins in the middle of her book, “This enterprise bears the title ‘Lecture on Poetics,’ but I will tell you at once, I cannot offer you a poetics. One glance at the Classical Antiquity Lexicon was enough to confirm my suspicion that I myself have none.” Instead, she offered: “I want to set a fabric before you. It is an aesthetic structure, and as such it would lie at the center of my poetics if I had one.”

Poetics

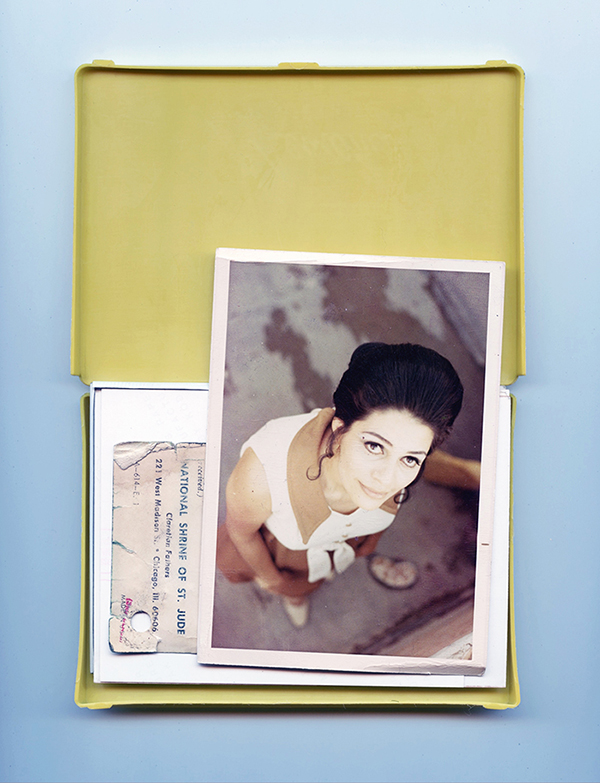

I had picked up Cassandra on a trip three months ago to LA to see my father. The book was my mother’s, part of her enormous library, which I had inherited but was too superstitious or too poor, or a bit of both, to put onto a ship to Europe, where I lived. I remembered Wolf’s book’s beautiful faded cover from my childhood. It had sat by my mom’s bed for years. When I started reading the book, it seemed a strange mirror: The book began with a trip Wolf took to Greece, where I have lived, in part, for some time. The book took form when, after a trip to Athens and Crete, Wolf was given the Adorno lectureship at the University of Frankfurt. Four lectures became four essays. The fifth became a rewriting of the Cassandra myth, a novel, about a woman whose voice was not heard, not to be believed.

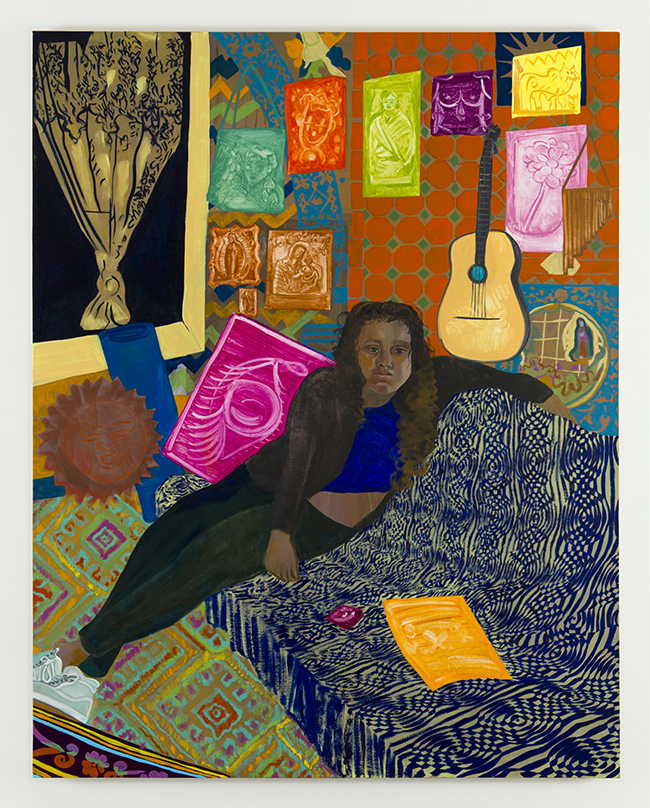

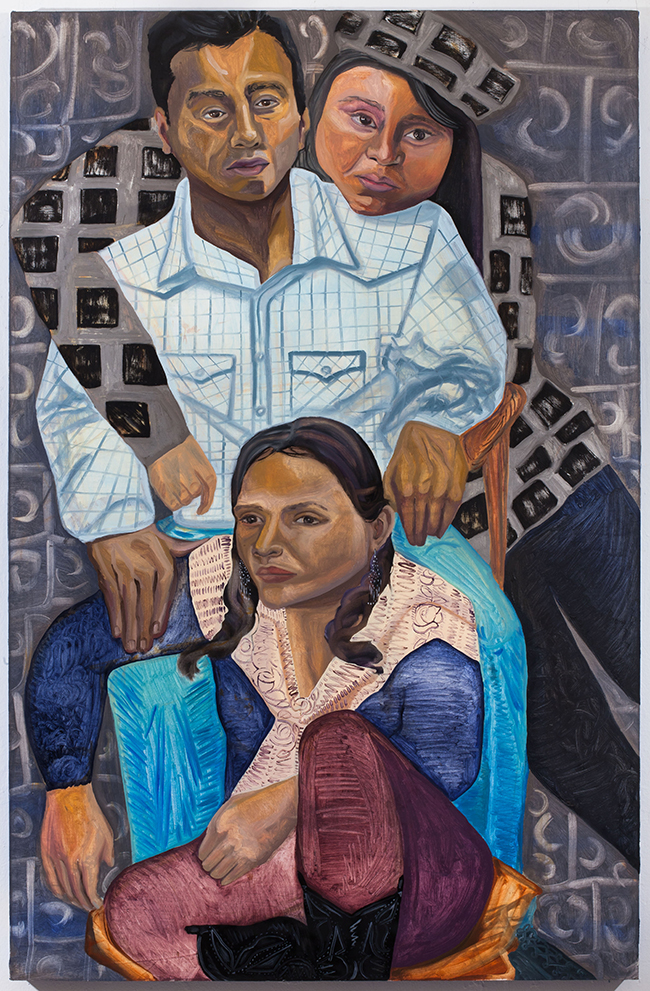

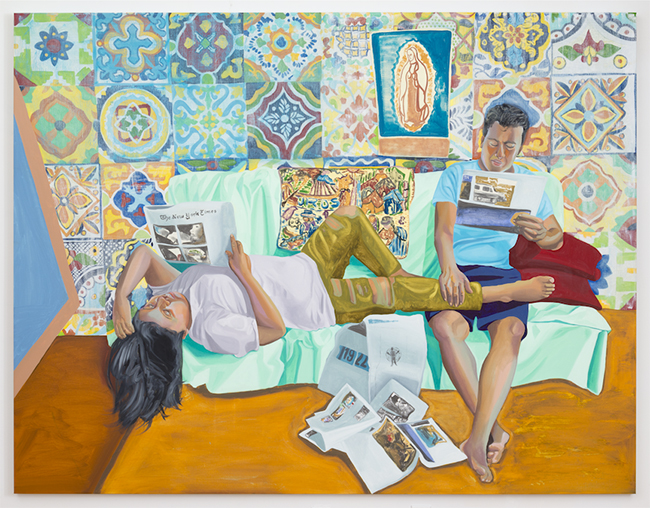

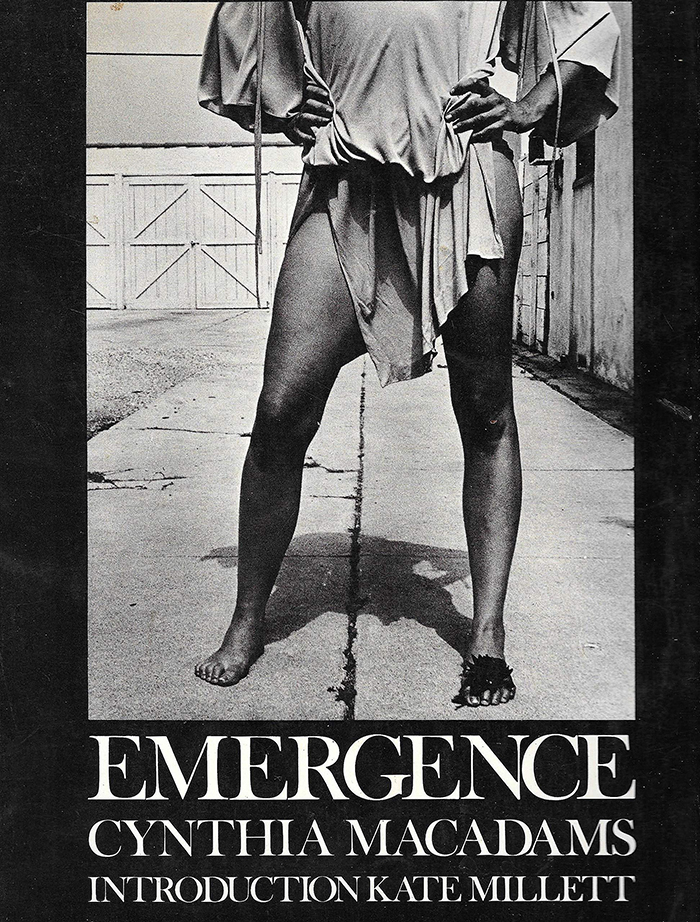

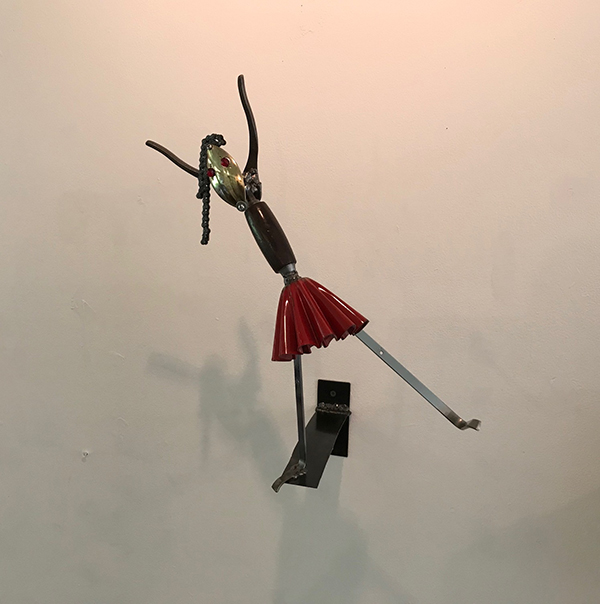

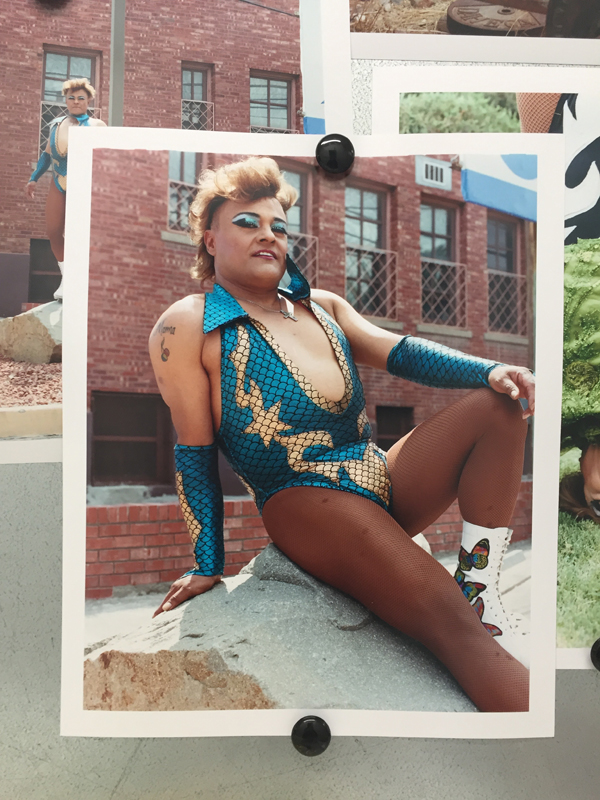

The Frankfurt lectureship Wolf was given was to be devoted to poetics, though the East German feminist writer insisted she had none. I felt that strange mirror again, looking back at me. I was currently curating a show I had titled “SIREN (some poetics),” which was to open in New York in the fall, and which brought together artists and poets whose work dealt with technologies of gender and sound, the bodies we build and break around the voice to make sense of it. That is, the visual languages in which our poetics sometimes take shape. The relations of text and textile were one aspect of the exhibition, so when I read that Wolf wanted to set a fabric before her reader—“an aesthetic structure”—in place of a poetics, I felt a jolt, some thrill.

Wolf writes: “‘Poetics’ (the definition reads): the theory of the art of poetry, which at an advanced stage—Aristotle, Horace—takes on a systematic form, and whose norms have been accorded ‘wide validity,’” Wolf notes. “New aesthetics positions are reached (the book says) via confrontation with these norms (in parenthesis, Brecht).”

I thought about that parenthesis. A week before the boat trip to Anafi, I had been with my students in Frankfurt, where we were part of a Städelschule project on Xenia, that is, hospitality. One morning I sat in on a lecture by the political theorist Nikita Dhawan, who noted Adorno’s (seemingly ungenerous and erroneous) comparison of Brecht and Beckett. But it was early and she kept confusing their names—B for B—which in the large warehouse room on the edge of the Rhine in industrial Frankfurt, a loud storm banging against its high, thin windows, seemed very Beckettian indeed. After her long and nuanced lecture on post-coloniality, drawing on the Frankfurt School, Dhawan made a joke about the misdirection of our desires, using as an example women and heterosexuality, and we all cracked up.

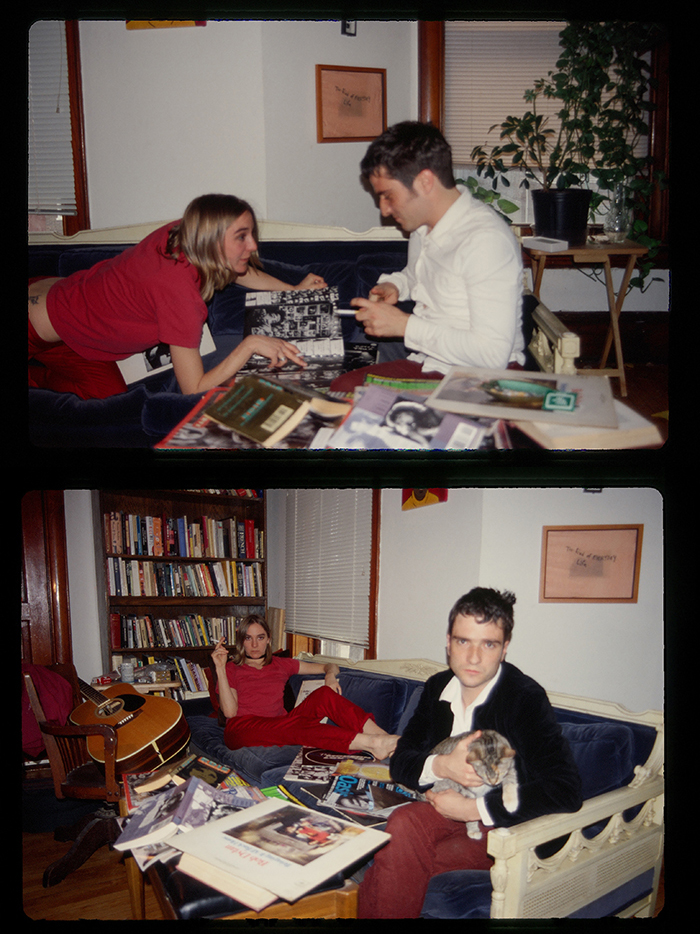

Prefaces

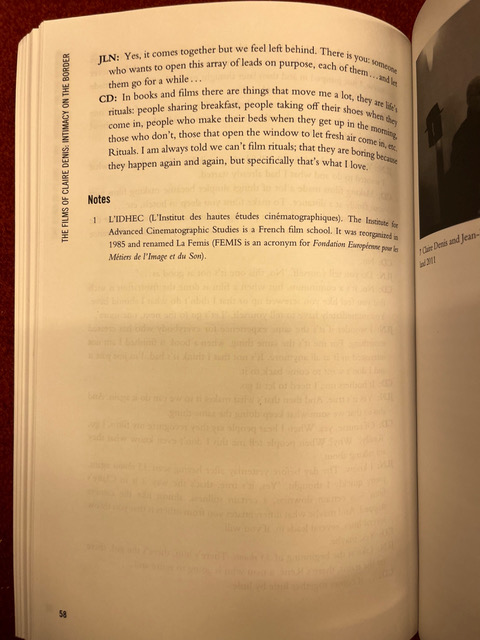

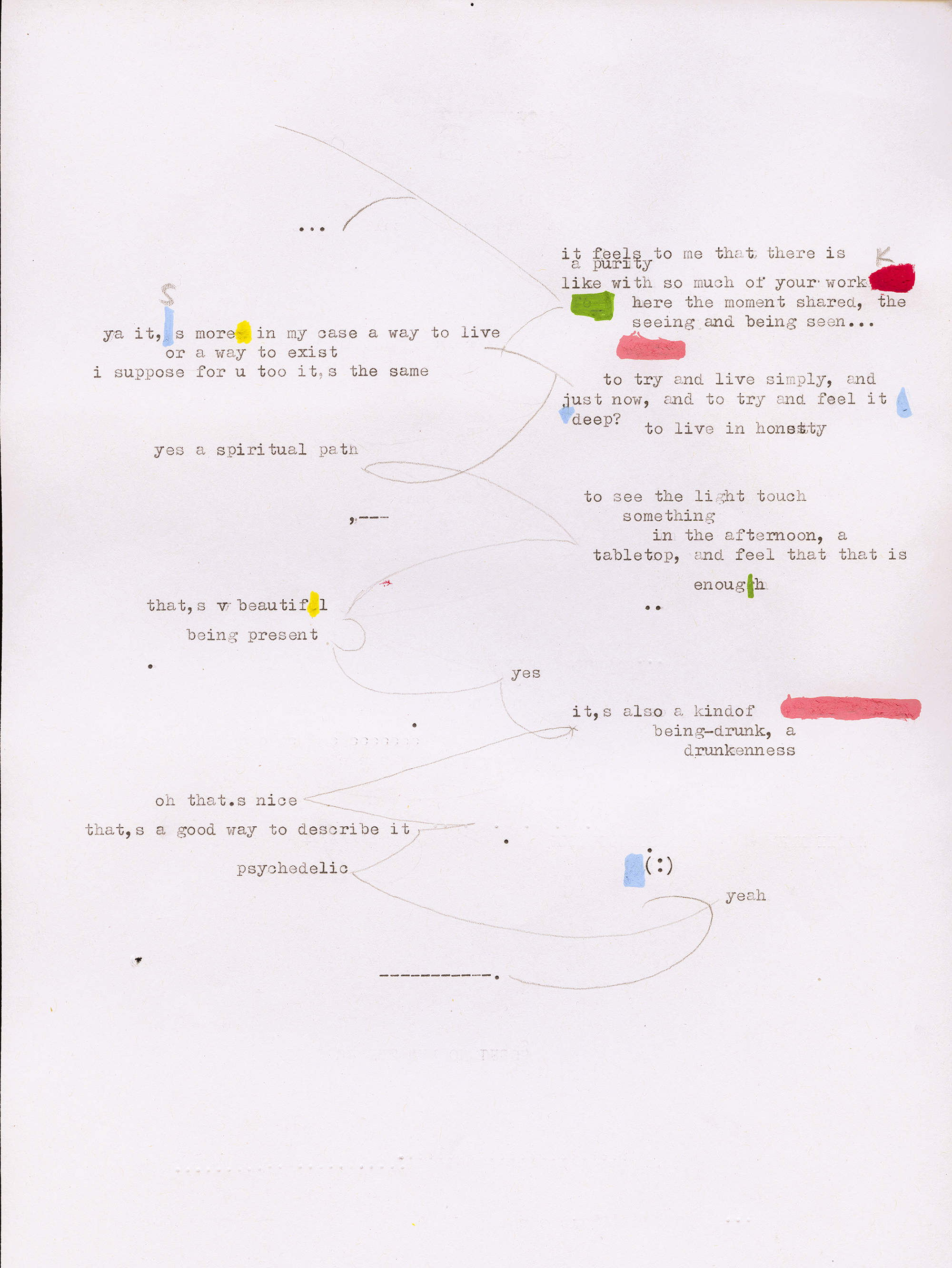

Accompanying me on the shuddering ship to Anafi, where Cassandra would go unread, unheard, were my partner Ion and two friends, Iris and Lisa, who all seemed less concerned about the wind than me as we picked at fries in the boat’s restaurant during a lull in the storm. It was our second trip together in a month. We had all been in Graz two weeks previous for Iris’s opening at the Grazer Kunstverein. To accompany her show, which Iris called “Appendage,” she had made a small book with the curator Tom and designer Julie, called Prefaces to Appendage. For it, Iris had asked each of us to write a preface to her exhibition. Iris and I lived near each other in Athens. We had spent years discussing our lives and our works, that is, our poetics (if we had one), so I used this material to write the poem I gave her for the book. I also used quotes from some of the artists and poets who would be in my exhibition in New York, Bernadette and Rosemary Mayer, for example.

Its title, I stole from Wolf.

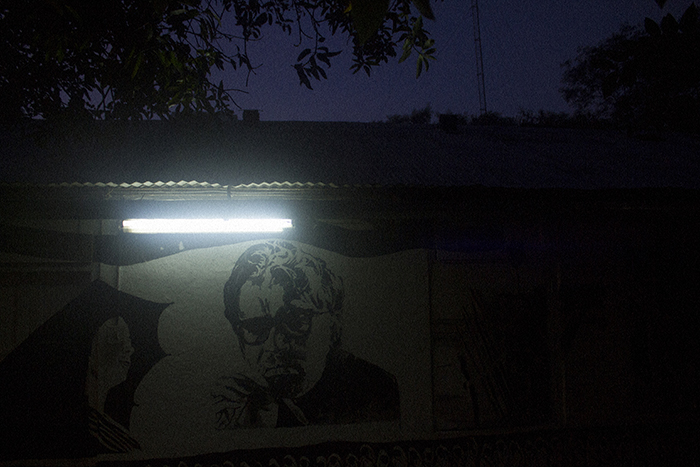

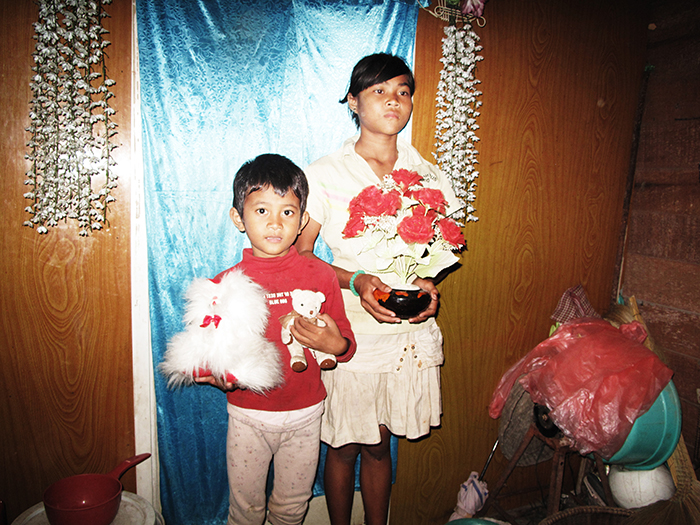

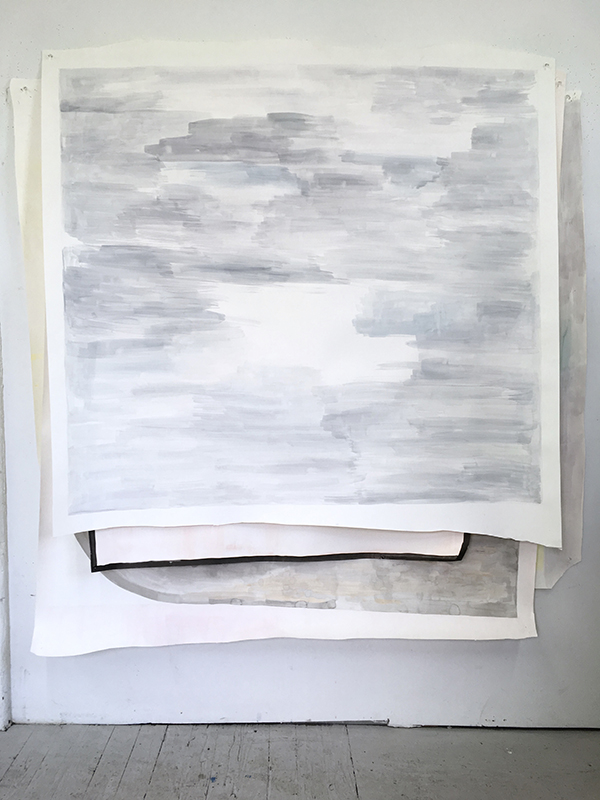

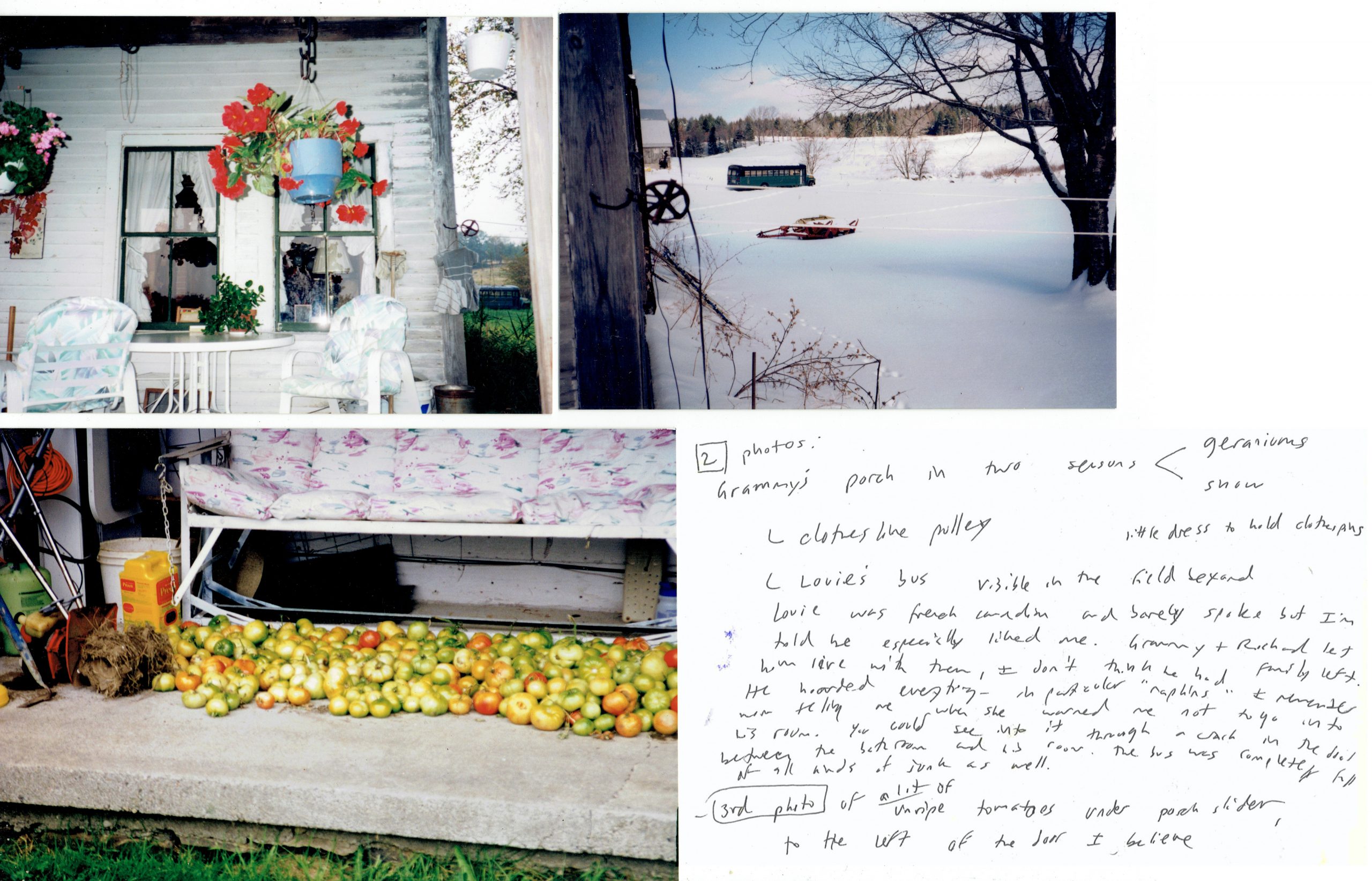

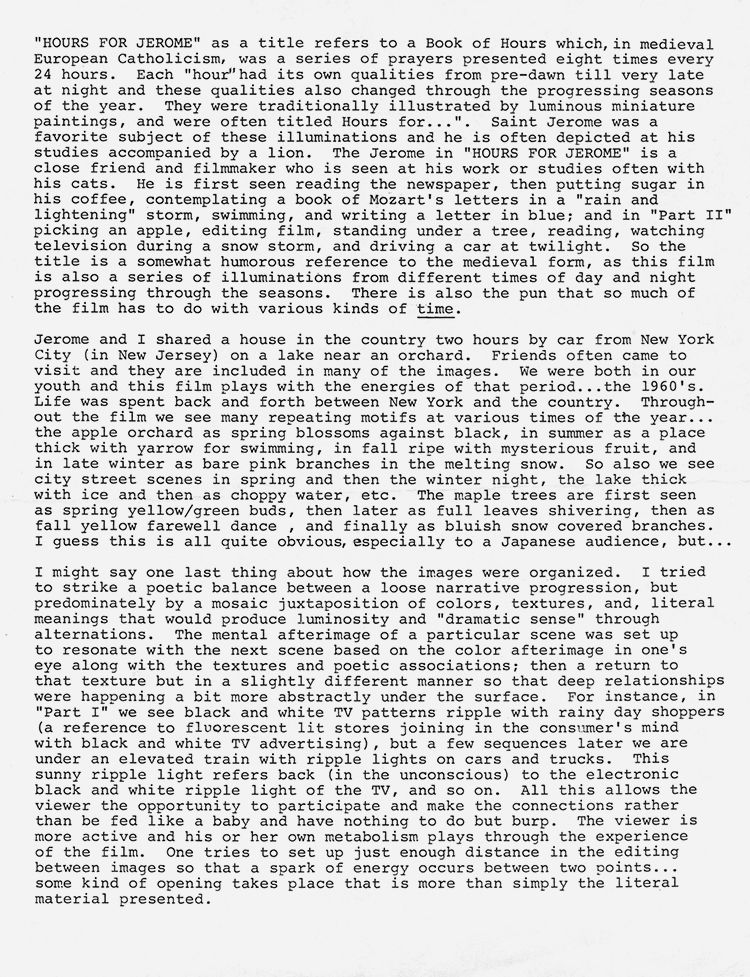

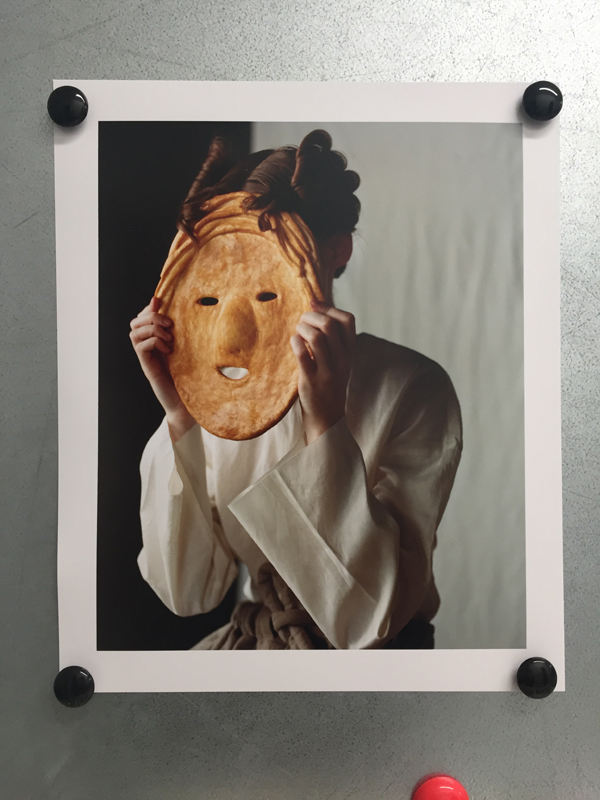

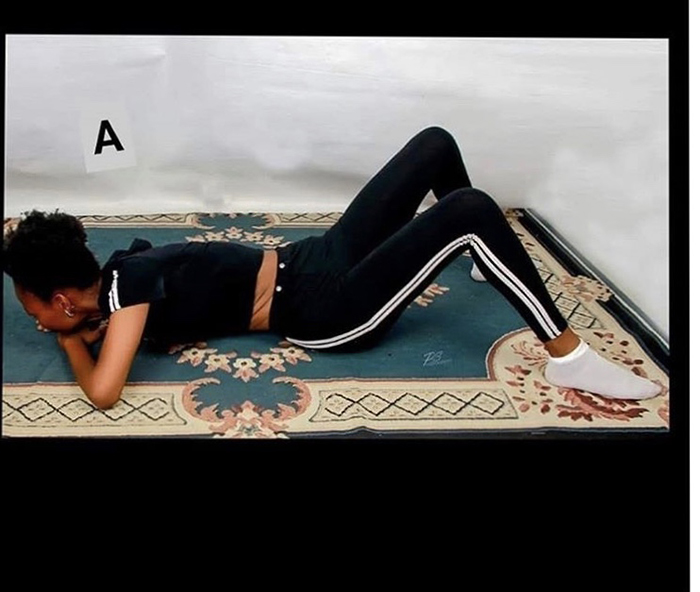

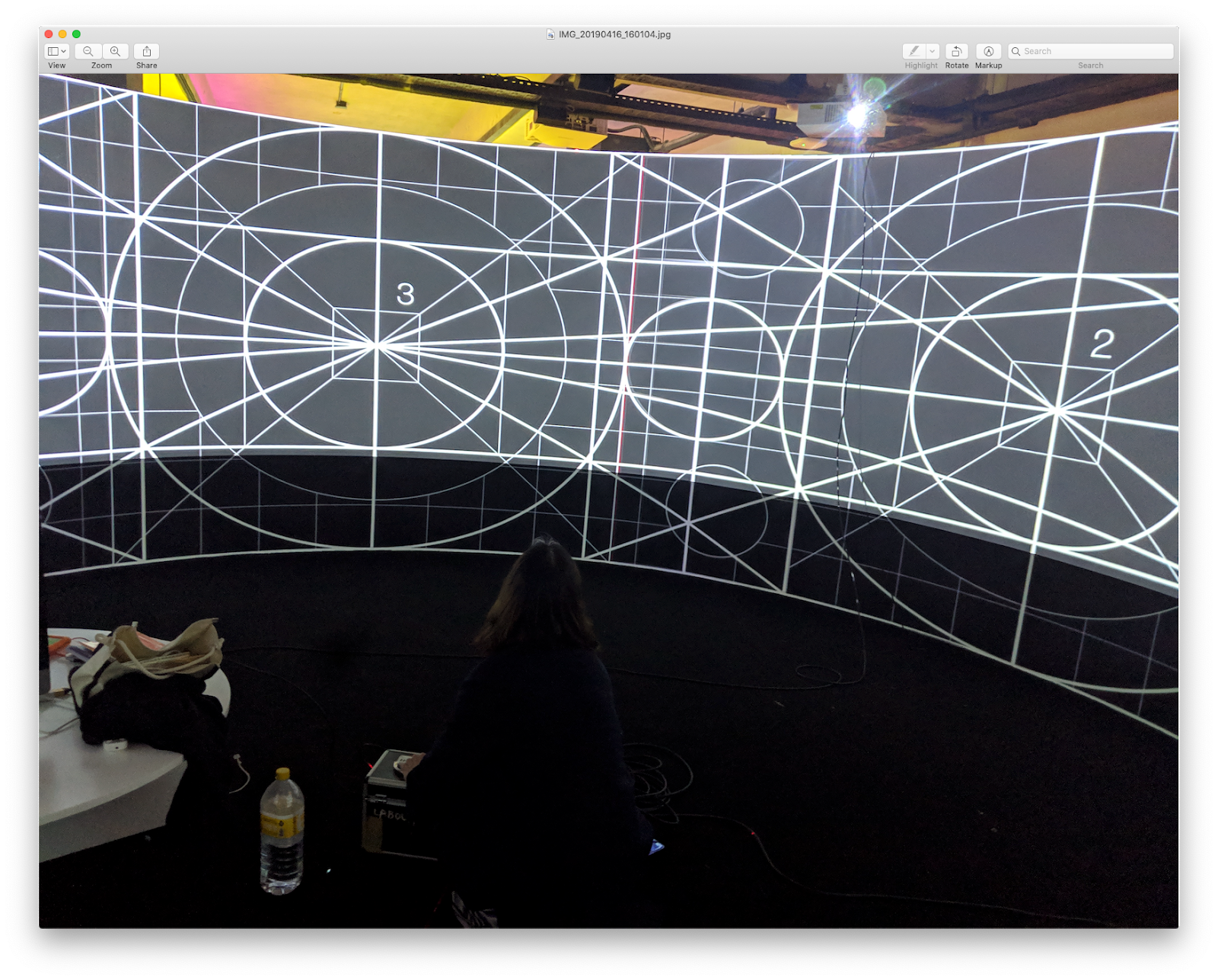

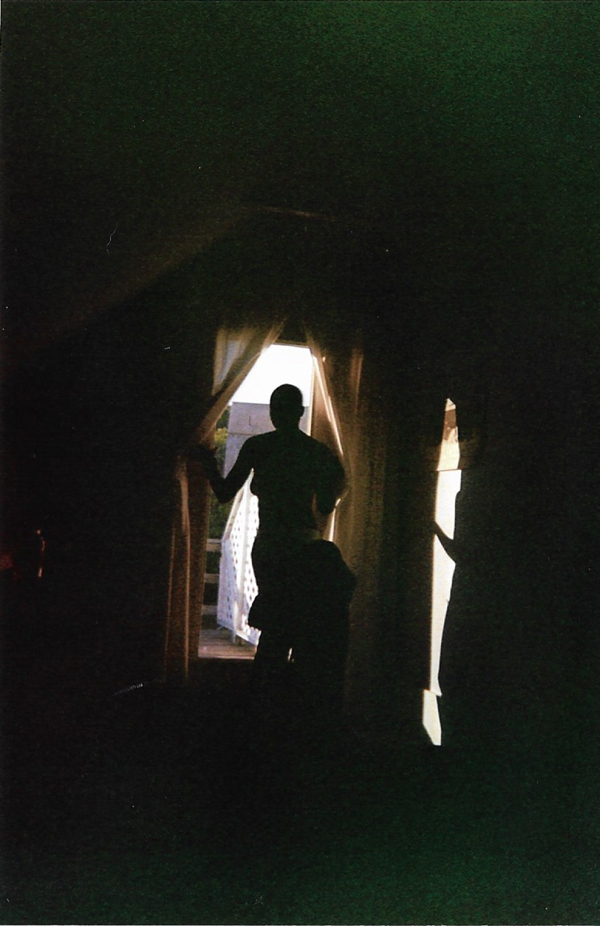

Installation view of Iris Touliatou, untitled (oral) and untitled (sweet and low), 2022, as part of appendage, 2022, Grazer Kunstverein. Courtesy of the artist and Grazer Kunstverein. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com

*

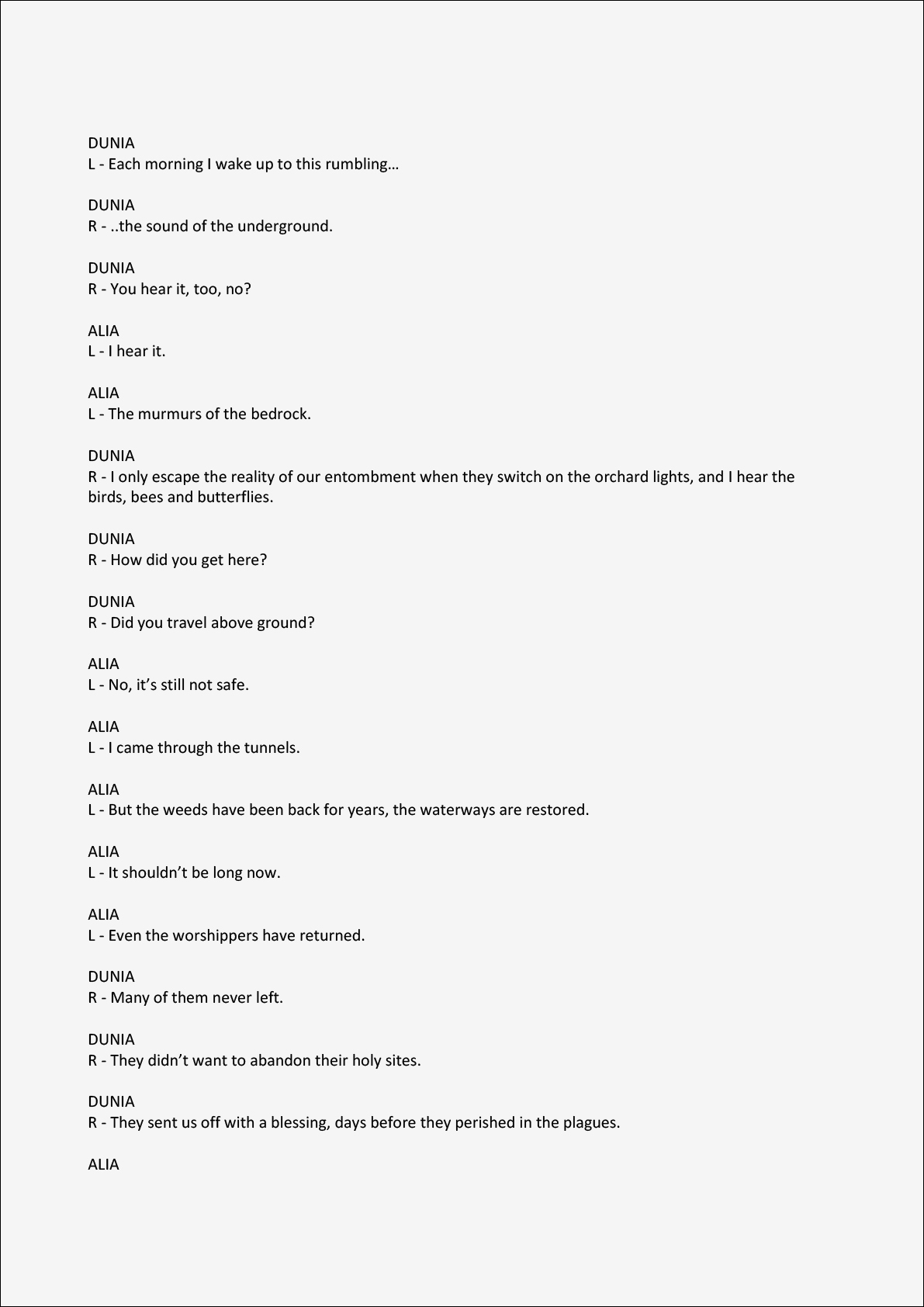

Conditions of a Narrative, that is, an Exhibition: A Preface

To write before one writes is to set a scene, to state the conditions of the narrative.

To prepare for happiness she arranges a prime-time spot of rehearsal, that is, yes, all preface.

Before she faces her face, she reads the epigraphs in the dirty mirror, which might strobe her book’s first pages, all allusion to be continued.

Before the Tibetan nephew of the physician of the last Dalai Lama gave her as supplement, pills for happiness, she packed a floor that made her strong.

Before I write I make coffee to pour over ice, then water the store-bought fern and the scavenged island succulents and the toxic oleanders, blooming pink and white in different measures across the terrace, always brighter along the dusty freeways than some windy city center block, but nevertheless an easy seed in a climate of exceptional heat and excellent women and weekly resignation.

To begin I pick up the book on the desk and read:

“I have this idea to imitate you though I do it in secret and attribute simple love to your idea of pleasure but before that I had an idea to write a book that would translate the detail of thought from a day to language like a dream transformed to read, as it does, everything, a book that would end before it started in time to prove the day like the dream has everything in it,”

Before I turn the page, I continue reading the stanza-like sentence, rising like a room of holding walls all around me:

“…to do this without remembering like a dream inciting writing continuously for as long as you can stand up till you fall down like in a story to show and possess everything we know because having it all at once is performing a magical service for survival by the use of the mind like memory.”

Before the exhibition, is the before of the mind, slowly turning on, like magic or memory.

Before she has it all at once her memory clicks on not as recording device but as material for creative function, and she hears, distantly told, a joke in which the architectural imaginary and the literary imaginary go on a date in which they discuss poetics and practicalities and the writing of rooms in rooms of rhymed quatrains.

Before I continue inside my hot, bright room, my little penthouse aquarium, I think about how she and I often talk about survival under the gloss of other words, other styles, our little drinks on the street and tête-à-tête a magical performance in service of poetics and possession and the rocky and mineral unholding of the present.

Before I move on, I remember that men in service were the goals on the short island vacation, as our friend manically suggested—a joke that lingers in our phones and in our minds.

To preface the text, I wrote thirty-three emails and ran three laps of Mount Lycabettus.

Before I begin the lecture I note that writing a letter is a practice of possession: to possess your reader by writing to them, binding them in your own language, your love, your address—Dear XX—being bars, being chain, being thread, being rope, being ribbon, being the ribbon of patisserie boxes, so collected from mothers. It blows around in the kitchen wind because the shutters are open.

Before the collection of prefaces is published, the book is bound and the exhibition is mounted.

Before the exhibition opens, before your eye opens, before the day opens, you take a drink of water.

Before the rains come, there is a half century of drought, and then super-drought, which no one attributes to the lack of ritual observance and symbolic sacrifice for which religions in arid regions have been organized for myriad millennia, per the German art historian.

Before we thought historically, we thought episodically, and this was the same thing.

To preface my interest in failure, I failed many times.

To preface a life of “nonreproductive making, unattained logistics, perverse infrastructures and missed opportunities,” there was a childhood in an arid coastal climate in the south and many trips to the north and the east. There were lab coats and bathing suits and bitter orange in winter.

To preface her movement around the apartment, she read: “Movement is what distinguishes infrastructures from institutions, although the relation between these concepts and materialities is often a matter of perspective.”

Before the boat departs, the island rooms are reserved and the tickets purchased.

Before she watches the video, she reads about historical realities and considers the art-trade in which she practices and the historical and structural schools to which she is indebted.

To begin her life, she must already be in debt.

To prepare for her life, she will take a long nap in the dark libraries with a pencil tucked behind her ear and a phone in hand.

Before she can sleep, she cannot sleep, and never will again. She fucks.

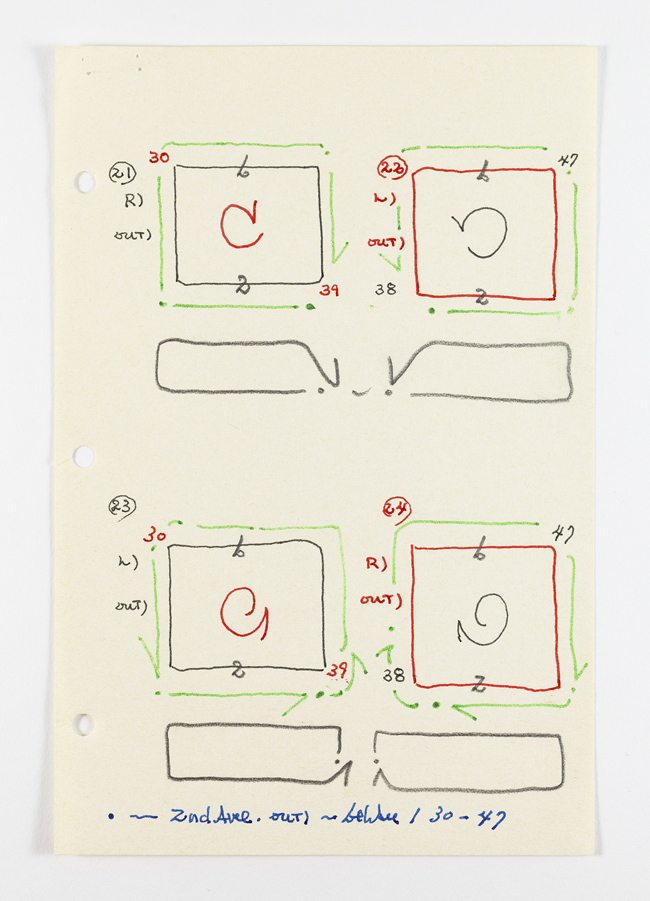

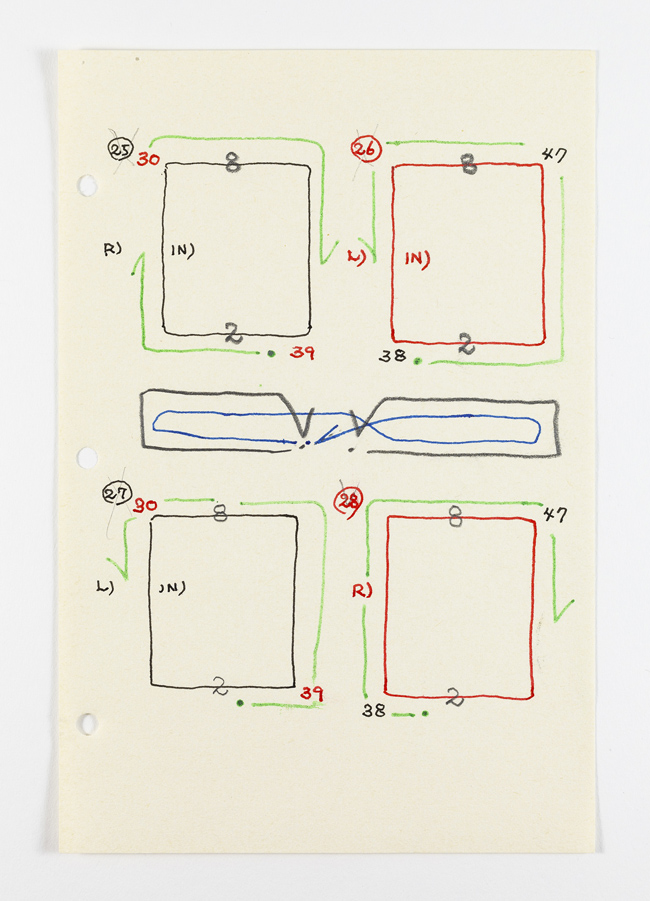

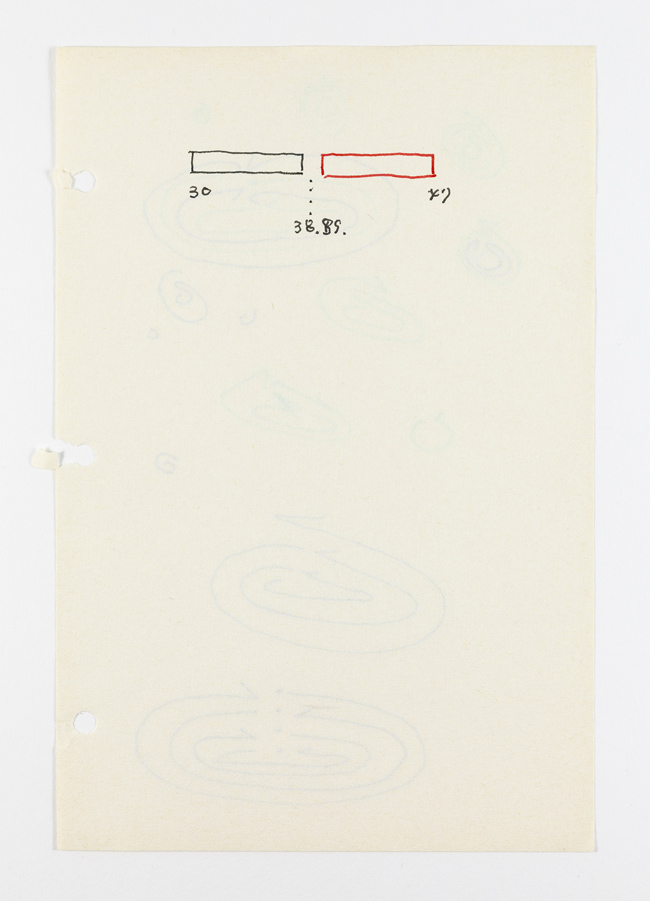

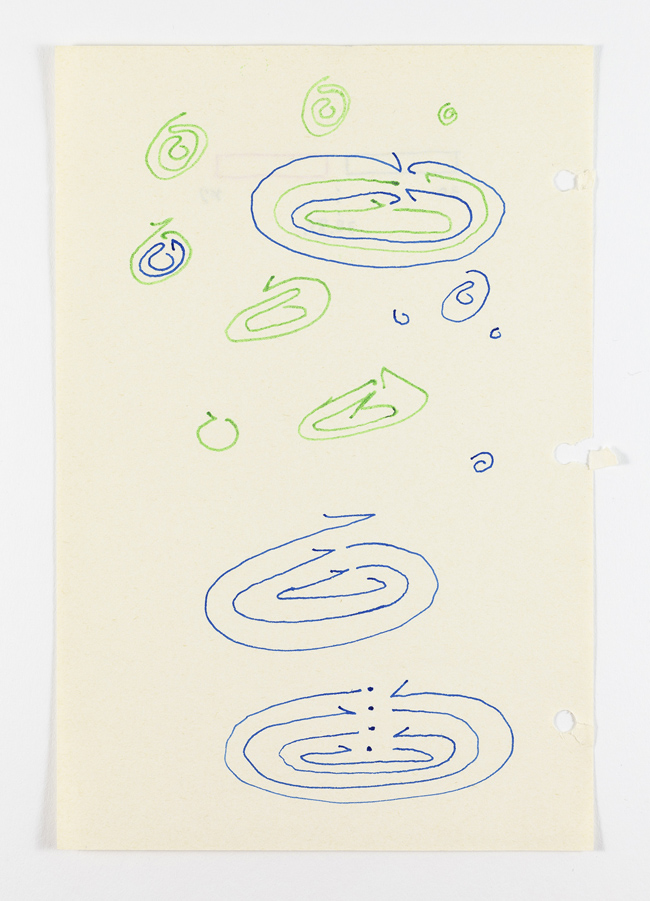

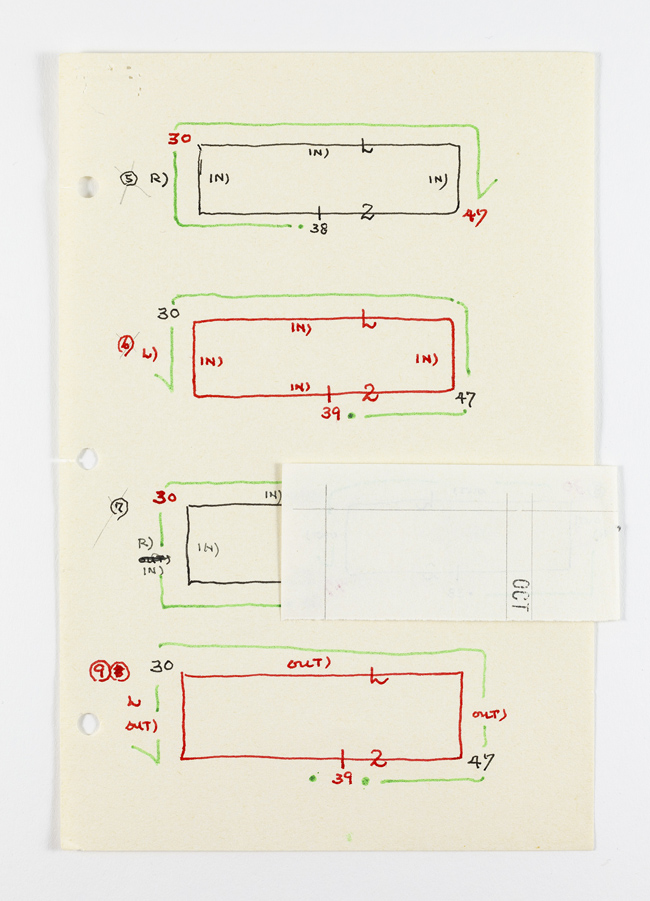

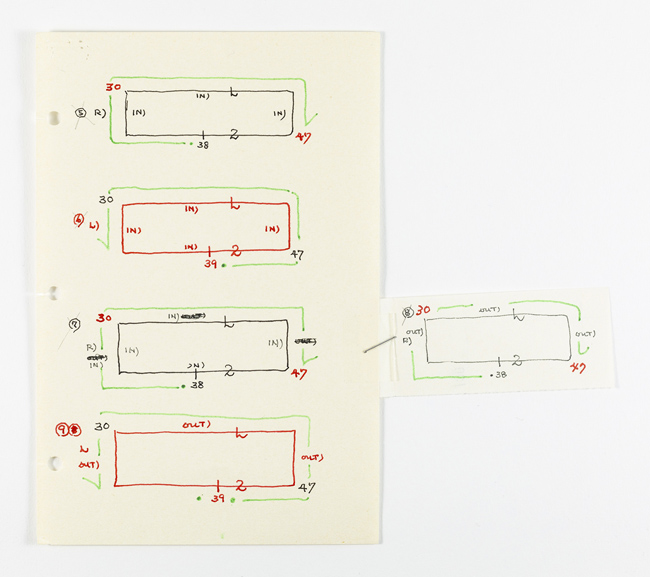

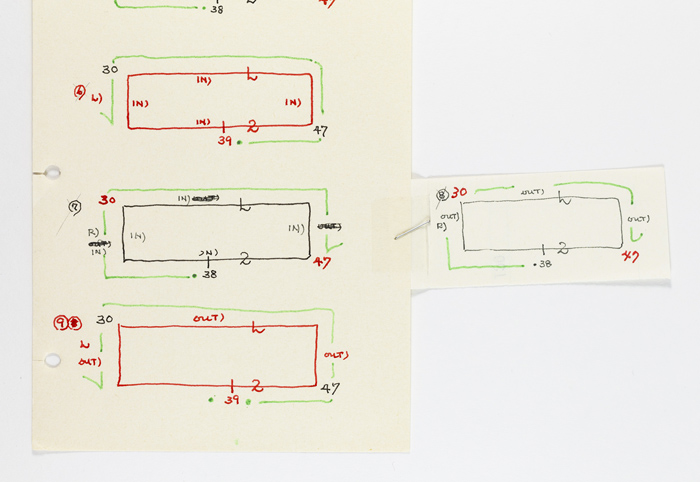

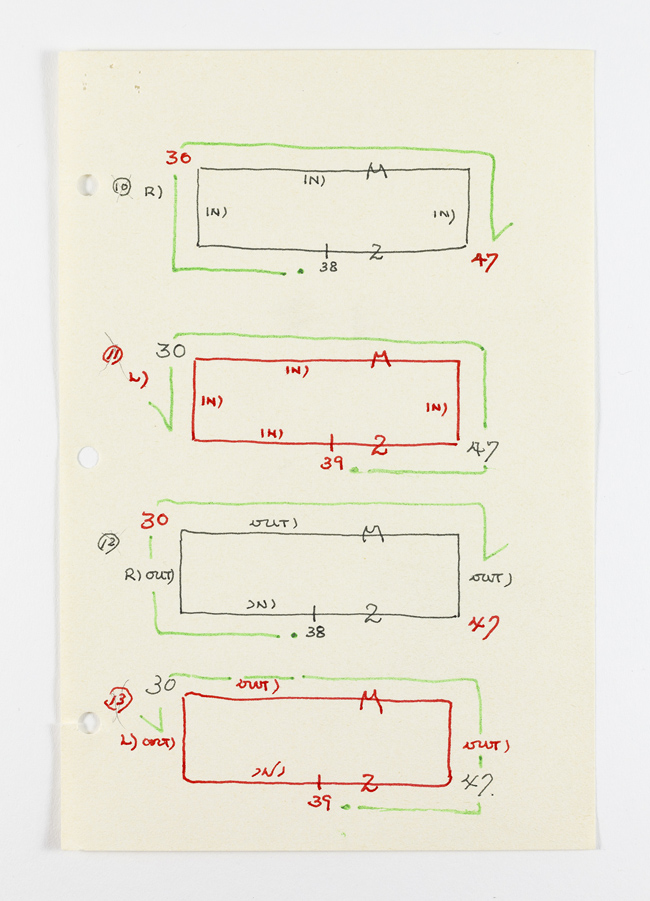

Before the drawings are shipped and hung on the walls, they are cared for and violently handled, again and again.

Before the lights burn out, they blink and buzz and stutter their light languages of green fluorescence down the dark reliquaries of deserted office hallways for about a year.

Before she had hope, she didn’t dream of hope—she walked in the ludic, ironic desert of factuality, alive with its insects and low animals, and studied the landscape’s red and pink contours which stared back, like an opaque, much-adored face.

After she woke up from the dream, she woke up from it again: this is what is called desertification or glitch or contemporary art history.

Before her current country, there was a previous country, and before that, another country—to each she looks back, strangely. To each she attributes an infrastructure of loving or shameful assembly, which previously she would have attended, but now knows nothing.

Before the animal lost its appendage, it understood its body as an assembly of iterations, performances, literary histories, bacterial commons, and it will again.

Before language streaks my screens, it wets and dries and wipes my mind, which is also a screen.

Before she held her attention, she held her in an infrastructure of desire in which they were both complicit and unaware and inextricably attracted.

Before the anthropological, there was the art historical, and before that the cellular and the ancestral, which are the same thing. Before I there was she.

Before the woman, there was the word, “woman.”

To preface “woman,” roll your eyes and open your mouth.

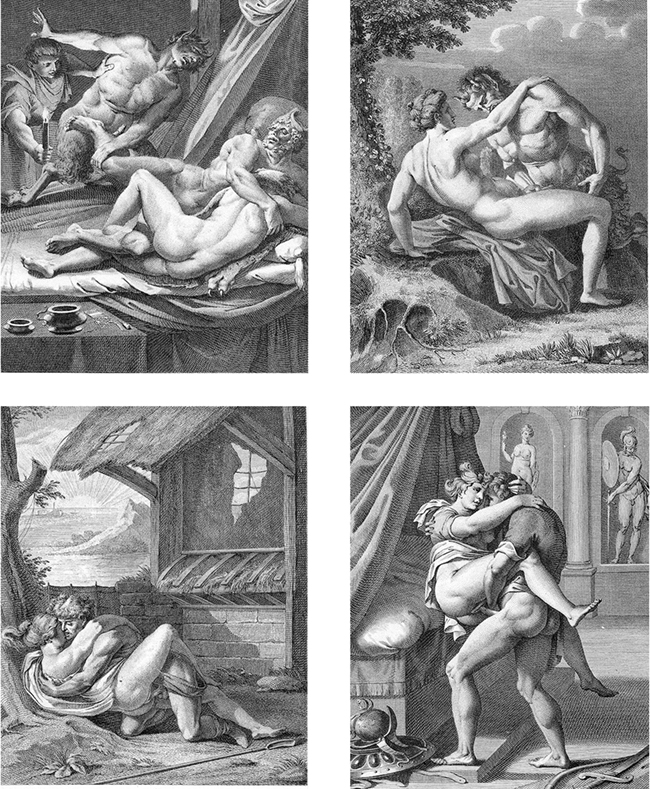

Before the myth of pale patriarchal supremacy, there was the pre-patriarchization of myths, in which every distance was not whitely strobed by colonnaded institutions of granular cruelty.

To prepare for cruelty, she acted cruelly.

Before the streets were burned every Friday night, the cops assembled so that the streets would be burned every Friday night. They smoked, bored, and drank cold coffees.

Before the elections, there were elections, and before the elected officials, there were the unelected officials.

Before she bought the organic eggs, she checked the date and her wallet.

Before the land borders, there were the water borders, and before that were international waters and underwater volcanoes and an ancient seabed studded with mytho-historical communities in which women labored for an aesthetics and a good time and were mostly held prisoner.

Before the book falls apart, it is thoroughly communicated in sober or excited tones at various sweaty gatherings of increasing and decreasing import.

Before the relationship falls apart, there is the feeling of true knowledge and some mineral and laconic pre-knowledge that you, like a child, attribute falsely to fate and its special offerings.

To preface the public online conversation, she tells them she loves them and then sits with an odd expression and in anticipatory silence.

To prepare for her preface, she takes one suspect pill and rubs in two drops of oil.

Before the gallery, there is another gallery, and before that, another. Each have a door, and before that, a light breeze, pausing thoughtfully. The doors are open and the artworks wave you in with their infrastructural violence.

Before the letter can be sent on letterhead, the paper is ground to a pink pulp then thoughtfully distributed by some light breeze to its intended recipient.

Before they wanted light, they wanted dark, and before that they wanted nothing. This is a lie: we have never not wanted. It is like a succulent: how much do you water it?

Before the apartment there is the terrace and before that a fragment of the expected economy—broken for most, stupendous for a few—and excellent view.

To preface the day of meetings, I arranged my face into a poetics of inaction, an aesthetic structure.

To prepare for sleep, they left the taverna for a terrace where they drank warm beer under an enormous cypress which sometimes bent in the wind like a woman in black.

To prepare the rooms, the fixtures were tightened, the fake silver armatures traced with a deft, tired finger.

Before the infrastructure was some desire—like a room, outfitted with fixtures for future furnishings, but unlit by light as of yet—which the hungry body contemplated, with style and anxiety and a kind of literate and ardent buzzing, like the hum of energy-saving fluorescence.

Before the speculation, there was poverty, and after it there was too.

To prepare the rooms, she ground the paper to a pink pulp: letterhead with no letters, love with no addressed object.

Before I write this, I read her emails, text messages, litanies of material and anecdote and fixture and gossip and citation and adoration and anger, all of our shared and seismic languages.

To prepare the exhibition, a studio is shaped in her own image and in the image of the communities that live in the streets around it. There are exactly four languages spoken and seven languages forgotten. A community is angered and the addict’s clothes are ripped from him. A neighbor tosses more down from his terrace.

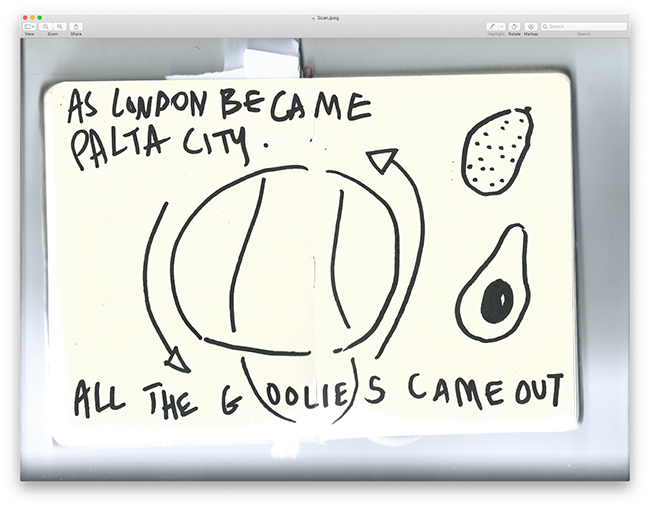

To preface the sacred music of the community’s conversation, a drone is sounded through the streets, its long notes as ambient and granular as sugar, and they thought it was siren, not beautiful.

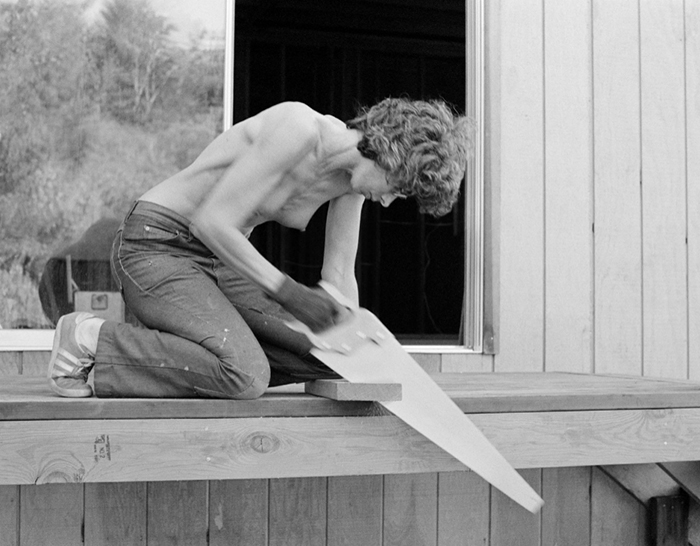

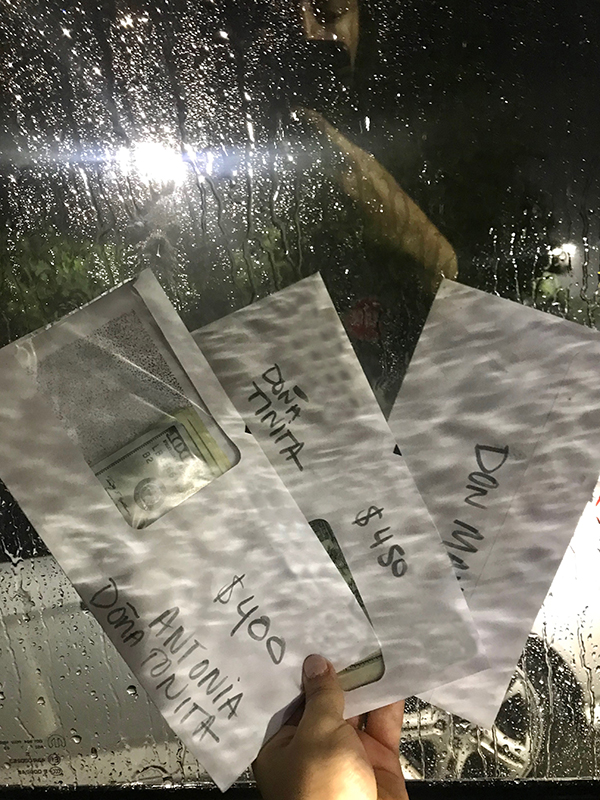

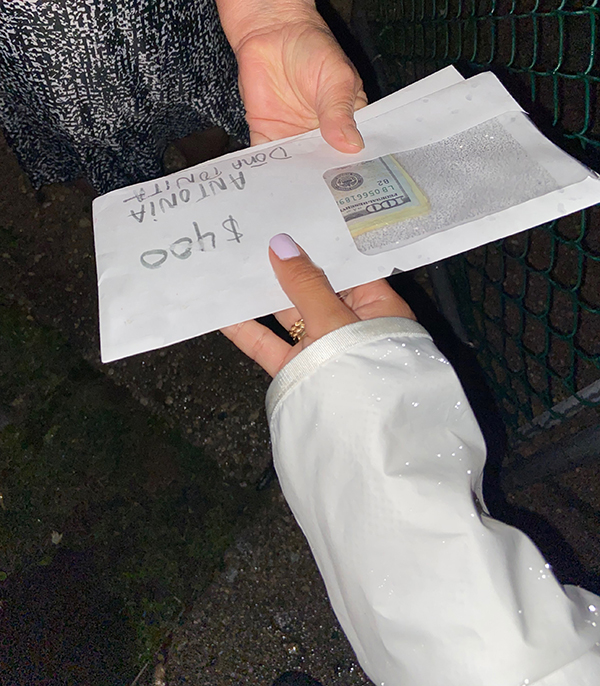

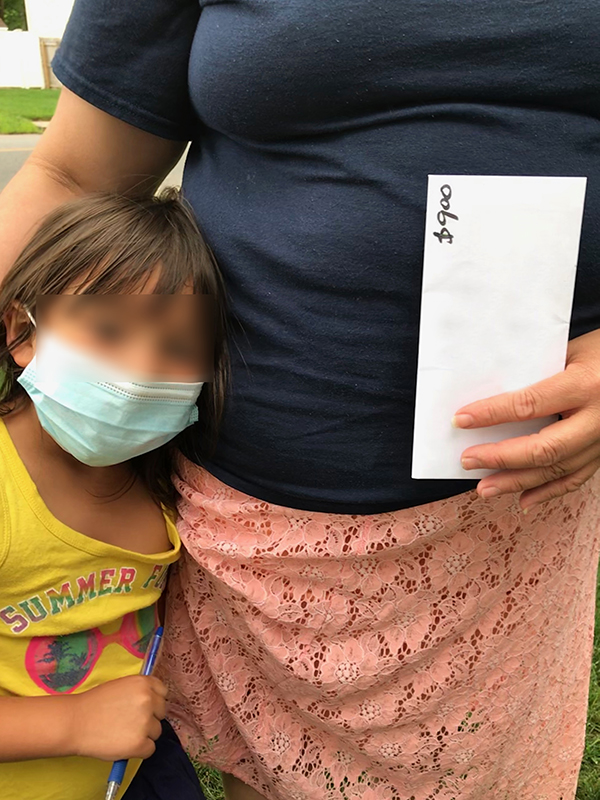

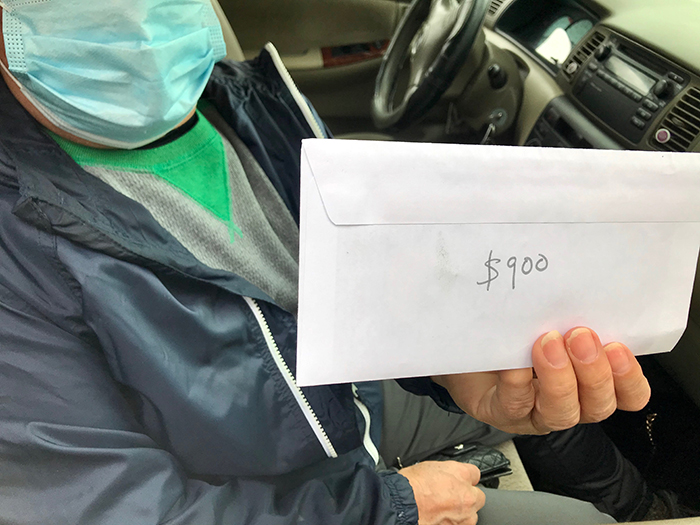

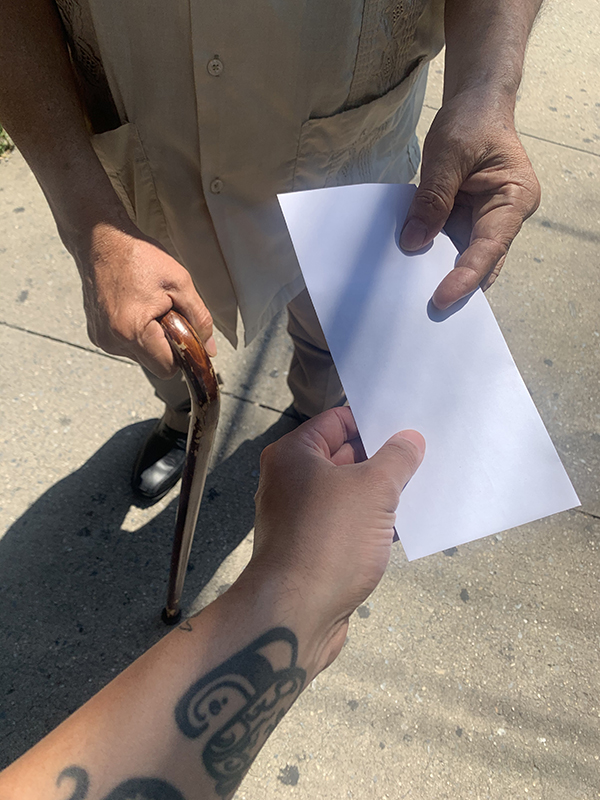

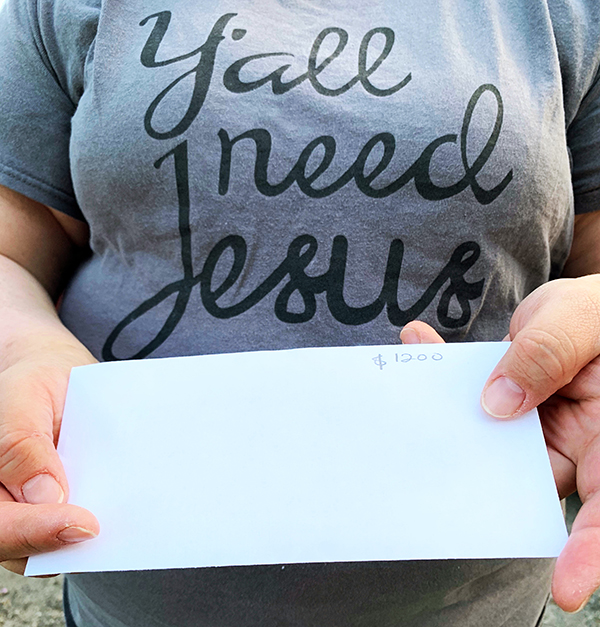

To prepare the public, they held a series of private encounters in which negotiations were led by bodies tanned in discrete infrastructural parts, that is, outdoor labor.

Before they left for summer, they paid the rising bills of public utilities and read the strange taxes in small fonts offered in two languages, both economic. The taxes were more than the bills themselves.

To prepare the closing of the company, they started a company. Failure like some easy ambient music filled the room.

To deinstall the show, they first installed it, drilling holes and hanging frames and taking time for lunch, which they ate at their desks, quickly, answering emails with untoward and accidental affection and delayed clarity.

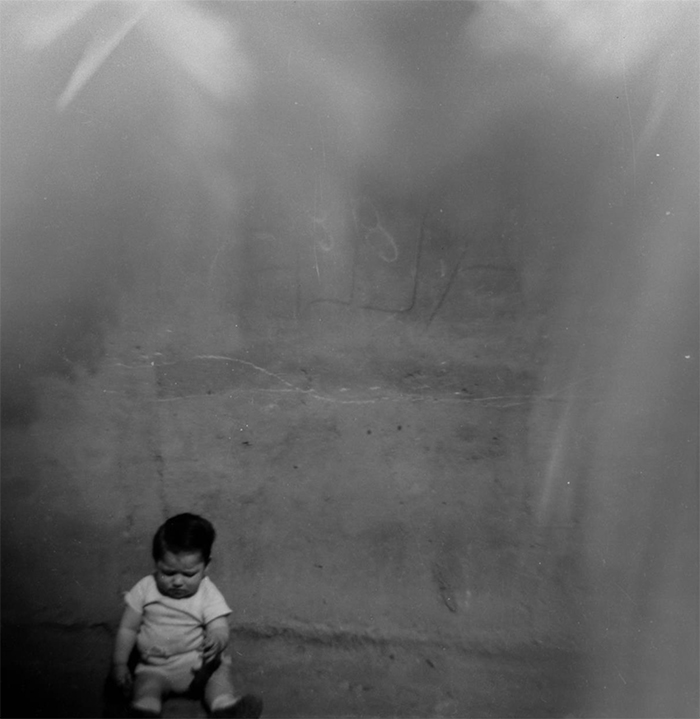

Before she could hold or be held she had to build and stabilize the holding walls, and before that she had to be born.

To preface their friendship, there were a series of economic collapses, personal collapses, mixed feelings, and educational opportunities taken and professional paths waylaid. There was an inoperable system in which they would appear to operate, that is, live.

Before the war, there was the interwar period, and after, the postwar.

Before the art institution, there is a city, and before that a universe of things, actions, and bodies, and as both preface and afterword an index of excavations of previous settlements and a poetics.

To preface her poetics, she had to state she had none.

To preface her exhibition, she had to find a language in which to accurately state the conditions.

To preface their relationship, they must have moved to the same city.

To preface a preface, you touch the dirty screen with your dirty mouth. You move your fingers over the sticky keys. You take a drink of water.

To preface the performance of making an exhibition, you set inside the rooms an aesthetic structure.

To preface what I write here, I must state: It is a language of making and memory that runs forward, like a machine. The body is not a machine, though, moistened. It is dry appendage, all fluorescent limb, brightening and dying. It is a theater of gesture: iteration, rehearsal, electric and clerical, it is a loop. It is a floor, a period piece.

To preface the chorus, she sings: we work on the floor / on the floor / on the floor / we work on the floor.

To preface the next I have the mind to imitate you, your labors and pleasures. In language.

To preface the chorus is a circuit, liquid and hissing, staging some formal—what—desire for what comes next. On the floor, open the doors.

Note: With nods to and citations from Lauren Berlant, Bernadette and Rosemary Mayer, Christa Wolf, J. Lo, and Iris Touliatou—for their words and fixtures.

Quinn Latimer

July 2022

“Conditions of a Narrative, that is, an Exhibition: A Preface,” first appeared Prefaces to Appendage: Iris Touliatou, edited by Tom Engels, designed by Julie Petters, texts by Tom Engels, Lisa Holzer, Quinn Latimer, Arnisa Zeqo (Grazer Kunstverein, 2022).

—

Quinn Latimer is a California-born poet, critic, and editor. Situated between the performance and the page, her writings take in feminist imaginaries of literature and the moving image, culture and its many natures. She is the author of LIKE A WOMAN: ESSAYS, READINGS, POEMS (2017), SARAH LUCAS: DESCRIBE THIS DISTANCE (2013), FILM AS A FORM OF WRITING: QUINN LATIMER TALKS TO AKRAM ZAATARI (2013), and RUMORED ANIMALS (2012). Her writings have appeared in Artforum, The Paris Review, Texte zur Kunst, The White Review, and elsewhere. Her readings and visual collaborations have been featured widely, including at Chisenhale Gallery, London; Centre culturel suisse (CCS), Paris; REDCAT, Los Angeles; the Poetry Project, New York; Sharjah Biennial 13; and the 14th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale. She was editor-in-chief of publications for documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel. Most recently, she is the co-editor, with Kateryna Botanova, of AMAZONIA: ANTHOLOGY AS COSMOLOGY (2021). She is curating SIREN (SOME POETICS), set to open at the Amant Foundation, New York, in Autumn 2022. Latimer is Head of the MA program of the Institute Art Gender Nature HGK FHWN in Basel.