I started a dream journal about three years ago. In the morning I would wake up with a certain feeling, a feeling that wasn’t necessarily tied to anxiety or terror, but a residue of something unresolved. I would get frustrated with myself for not knowing why I was feeling the way I did, then I’d suddenly remember my dream in the middle of the day. Despite knowing full well that nobody really cares about other people’s dreams, I couldn’t help but tell my dreams to whomever happened to be around, usually my roommates. I would begin with what I thought was an accurate description of the dream, and at some point I’d catch myself making stuff up, knowingly or unknowingly, adding and omitting details to make the dream into a sensible narrative. I can now see that recounting my dreams was a self-soothing reflex, an attempt to outline the unresolved tensions of the unconscious using the tools of language.

The sensation of recounting my dreams felt very much like that of making art. I found myself trying to make sense of something, and in that process of “making sense”, a lot of things became distorted. In remembering my dreams I felt like I was witnessing myself from a distance, peering into my own psyche from the threshold between my conscious life and the unconscious–I felt as if I had become a foreigner to my own mind. I’m interested in this aspect of dream analysis as it relates to art-making: each requires the ability to observe from the threshold of subjectivity and the courage to stand firmly on that threshold of mystery. What I’m starting to realize is that both dream analysis and art-making are about resisting the urge to fully understand.

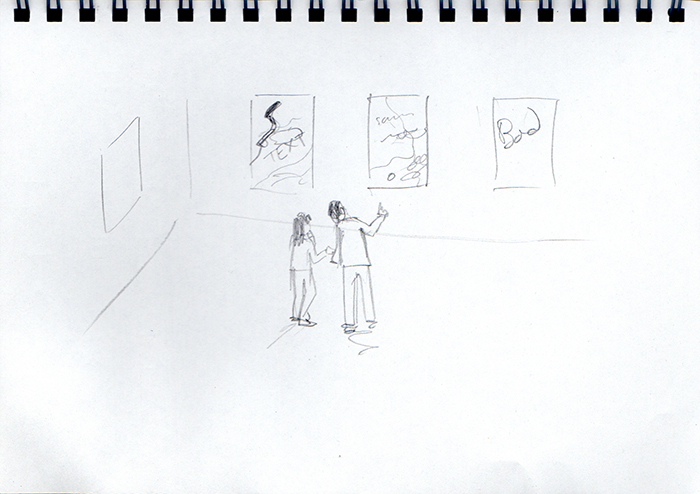

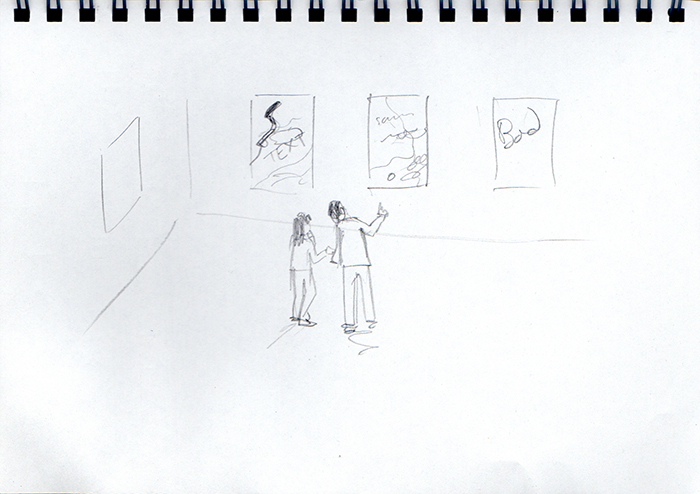

Here are some of the entries from my dream diary that I found to be exceptionally hilarious. Time after time I find it amusing that my mind is working very hard (and overtime) to say something very simple, predictable, and ultimately not that interesting. Another part of my dream journaling was jotting down my own analysis and making a quick sketch from what I could remember.

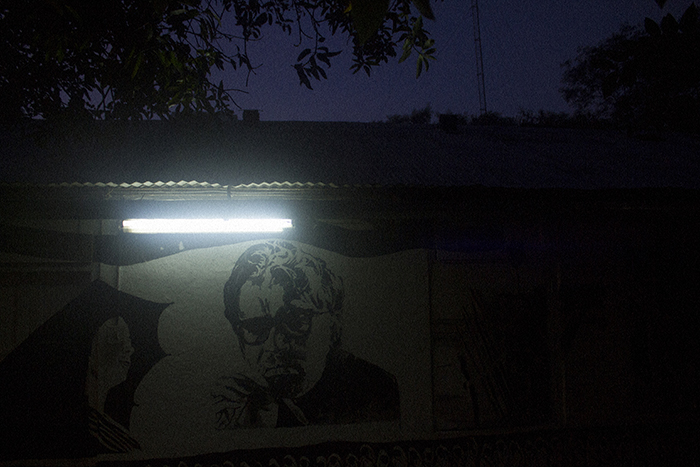

March 28th 2021

I had a dream that I had just opened an exhibition. A stranger came by the gallery, and I pretended not to be the artist of the show. We started talking, and looked at the paintings in the gallery together. The stranger began telling me that he really didn’t like the work. And he kept telling me why he didn’t like the work, and I’m not sure what he said exactly but his comments were all negative. At first I was curious, so I kept our conversation going, asking him more questions and listening to his replies. I remember I wasn’t angry or offended, but intrigued by the stranger. And at some point in our conversation I looked up and saw the paintings on the walls, and I was genuinely horrified by what I saw. The paintings were truly awful. They all sort of had this web art look, like abstract marks all over the canvas but they were made with MS paint scribbles and they had all these overlapping texts, which I couldn’t make out. In the dream it was clear that they were my paintings. I was just in total shock that I had made them and they were on display for everyone to see.

Notes:

Projecting/displacing my own doubts about my work (figurative/representational) onto artworks that clearly don’t look like mine (abstract/process-based). Coping with my own insecurity because I can only be horrified by works that don’t look like my work–> in denial of my own failure.

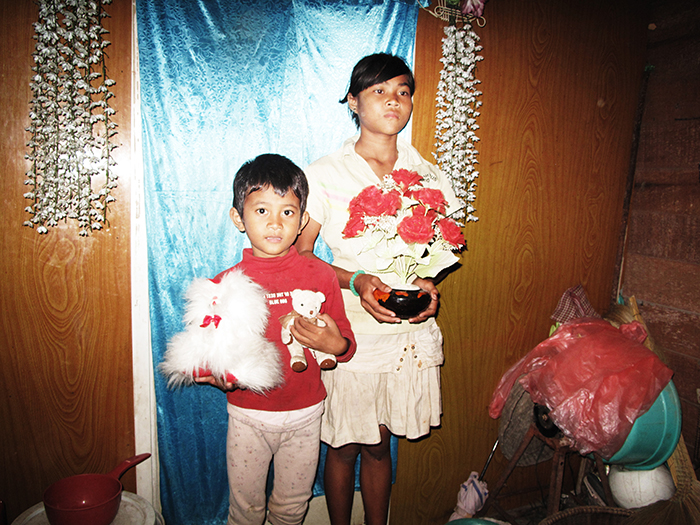

March 24th 2020

Just had a dream that I was at my cousin’s wedding in Korea. I don’t remember which cousin it was, it was a generalized idea of “a cousin”. The wedding wasn’t held at a church but the place reminded me of a gym or a convention center, a kind of place I’d associate with bible camps I used to go to as a kid. As part of the wedding celebration, my cousin started playing his guitar and it felt like he was singing a gospel. All the guests were now sitting on the floor, in a circle, and they were singing along, clapping, crying, swaying, speaking in tongues, almost like the over-the-top evangelical services I would see on television. People in the dream were all very ecstatic. I looked around the crowd and at first I felt really embarrassed for them. And then later I thought to myself, in the dream, that I wished I had their conviction and their ability to feel this religious joy, which is God’s love, and not be ashamed by it. I looked at the people with a kind of awe. Then I woke up.

Notes:

Desire and repulsion towards the past. Anxiety about conformity, longing for a communal/group identity. Nostalgia for Korea.

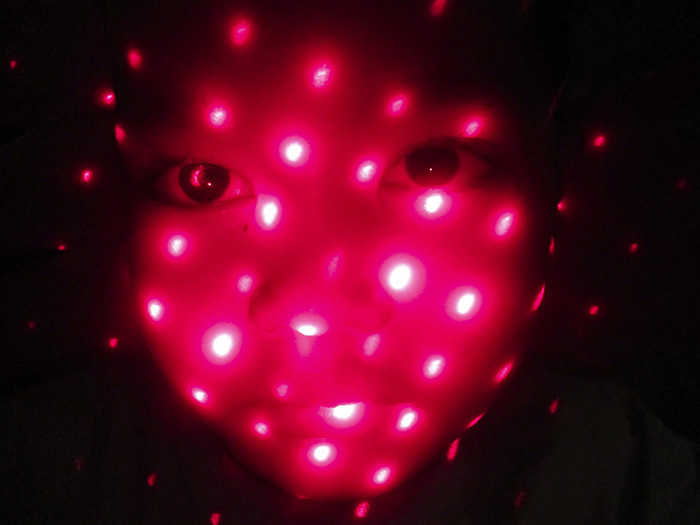

September 26th 2019

I had a dream that I was in a mansion with my family, a place similar to one of those gilded age Newport mansions. The mansion was gaudy and excessive, but was also beautiful in a strange way, filled with antiques etc. The context of the dream was that we were invited to live there with some important people. The people at the mansion were dressed in Victorian gowns and acted very properly and sort of robotically. There was a super old woman in a wheelchair, who seemed to be the head of the household. Everyone followed her around and people tended to her needs.

Far into the dream I realized that I can perform some kind of magic, one of those mind-command type psychic powers. For example, I could think “move that vase” in my head and the vase would float in the air, and I could move it around in the space with the tip of my finger. I was really excited to have this magical ability, and in the dream it was understood that this magic could only be performed within the confines of the mansion.

It was like a scene from Matilda. I was playing around in the mansion, moving objects around in the air, rearranging them in different rooms, when suddenly my dad whispered in my ear: “Look carefully. You think you are moving those things, but they are exactly where they had been. You didn’t do anything.” I was so surprised, but it was true. All of the objects that seemed to be floating in the air sort of disappeared and reappeared where they were originally. I was super confused at first but we somehow figured out that the people in the mansion have been putting hallucinogens in our drinking water. So I told my dad that we must not be fooled or seduced by the magical apparitions that were happening around us. Then my dad challenged me, telling me how we can’t really decipher what was real or an illusion, how we don’t actually know if we are hallucinating or we just think we are. Like, how could we know that we didn’t just make up the fact that there were hallucinogens in the water, and that our drinking water was actually fine, and that I could really perform magic? And I just remember feeling super frustrated and almost manic, because I couldn’t answer him. I think after a bit of arguing I yelled at him something like “There is a way! We must try!!” Something very melodramatic like that.

Sometime later we had to go find my brother and my mom, to tell them that we had to get out of this place, but during the search around the mansion we stumbled upon a secret room, where we found all of the mansion people performing some sort of an operation on the old woman (the head of the household in a wheelchair). We found out that the old woman was actually dead, but the people in the mansion were able to swap out her organs to make her corpse look fresh and alive. We realized that she had been dead the whole time, and that because of the water we’ve been drinking, we hallucinated that she was alive, and that the mansion people were actively taking hallucinogens so that they could lie to themselves and see her as being alive.

After learning about this, my dad and I kept trying to find my brother and my mother, and the mansion people realized that we knew what was going on, so they chased us with guns. We somehow got out of the mansion, and there were gunshots and bombings in the background, and my dream sort of stopped there.

Notes:

Anxiety and paranoia about assimilation. Aspirational wasp-ness as self induced spell. Dad as a philosophical guide who challenges my ego.

—

Cindy Ji Hye Kim was born in Incheon, South Korea, in 1990. She received her B.F.A. from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2013 and her M.F.A. from the Yale University School of Art in 2016. Recent solo exhibitions include: Casey Kaplan, New York (2022); Francois Ghebaly, Los Angeles (2021); MIT List Visual Art Center, Cambridge (2020); Helena Anrather and Foxy Production, New York (2019); and Interstate Projects, Brooklyn (2018). Kim’s work has been featured in ArtForum, Art in America, ArtAsiaPacific, Bomb Magazine, Brooklyn Rail, Cultured Magazine, The New York Times, and The New Yorker. Her work is in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles; Collection Majudia, Montreal; Sifang Art Museum, China; and the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence. She currently lives and works in New York City.

www.cindyjihyekim.com