FEAR AND LOATHING GOES TO HELL

— Hunter S. Thompson and I were professional acquaintances for about 20 years. Along with Nick Tosches, James Walcott, Grover Lewis, Lester Bangs, Robert Christgau, John Morthland, Chet Flippo and other speedy typists, we were what they used to call “new journalists”—free-style purveyors of “cultural reportage.” We wrote for the same magazines about subjects with the shelf life of milk. We prowled the same airports and lived the same sort of poorly regulated, profligate lives. Hunter, as it turned out, became famous for living this sort of life. Not one of us begrudged him his fame, since the toxicity of lurid fame was our one true subject. As Lester Bangs put it, our job was to report back to the kids in Omaha about the dead girl in the lobby. So if Hunter, who, like us, had seen the blood on the curtains, wanted to be Mick Jagger, he was welcome to it. And he had a right, because Hunter Thompson was a very good writer, a wonderful writer, in fact, for a one-trick-pony who did lyric bile, fear, loathing and rabid denunciation without much else in his quiver.

Given the times, of course, lyric bile was usually sufficient, but, as a writer and a person, Hunter was never in a place you wanted to be. It was no fun, and Hunter himself, whose life was redolent with opportunities for fun, never seemed to be having any, unless he was laying waste to something or someone. While you were chatting up the Valkyrie in the fuzzy, scoop-neck sweater that could barely contain her awesome, quivering breasts, Hunter was spraying the room with a fire extinguisher. This sort of jackass intervention was extremely exasperating. Eventually it became sad or disgusting depending on your generosity.

So if we, his fellow scribblers, begrudged Hunter anything, it was not his lifestyle. It was his writing about his lifestyle and, in the process, outing of our lifestyles by telling people what we were doing. There are some creatures who like to dance but do not like the light, and, for nearly a decade, before Hunter became a “name”—before “rock writer” became a part you played in the alley behind some concert hall—we were all invisible, a tribe of happy, insatiable shadows on the loose. We had all the perks of fame and none of the grief. We got the planes, the limos, the hotels, the good money and the back stage passes. We got the free cocaine, the speed, the smack and the barbits. We got the buffet, the tour jackets, the balconies and the beautiful girls (more of these than you can possibly imagine) that we selected after the band but before the roadies. Best of all, we got to write about music, to live in a bubble of music and music was a subject that never aroused Hunter Thompsons’s passion. He liked rich folks. If they were rich musicians, fine. He liked power players, Johnny Depp, racecar drivers, gun nuts, Hells Angels and politicians.

Hunter wanted to be the Sheriff of Aspen. We wanted to be Robin Hood’s merry men, because, being an inconspicuous merry man meant that when you were finally sated and demented, having sampled the spicy gruel of American celebrity, you could, if you wanted to, put on a Lakers cap and stroll away, just disappear into the night. Jimmy Page couldn’t do this, so he disappeared into his castle. So, when Hunter himself finally disappeared, when he shot himself, my first reaction was that it might have been slightly more respectful of the living had Hunter, who loved explosions, just strolled away into the woods and blown himself into slightly smaller bits. He chose otherwise, of course, and in the days after he died, a couple of journalists called for quotes. I told them that I liked Hunter as much as a lover could like a hater; from which I hoped they could infer that I meant “not very much.”

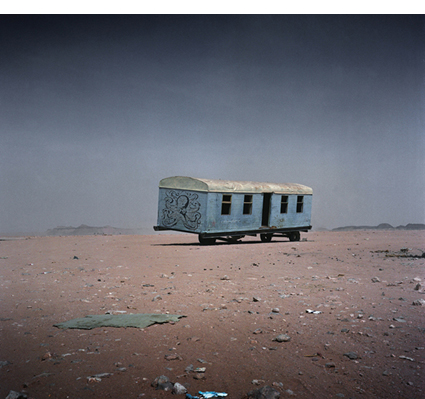

I did respect the dude, however, so, in his wake, I re-read Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. I found it as icky now as it did then. Laying the book aside I found myself, for the first time, feeling sympathy for Johnny Depp. My first beef with the book is that nothing happens in it that requires the city of Las Vegas as a setting. There’s no gambling. There are no money rolls, no whales, no whores, no crap tables, no showgirls and no scumbag hustlers. In fact, rereading the book now, at home in Las Vegas, it feels as if Hunter is simply not up to sharing the stage with the local color, no matter how vivid he might have felt. There is, however, a lot of desert highway in Hunter’s book, a lot of blistering Mohave, which Hunter mistakes for the landscape of the American soul. This is way too Hollywood to me. I love the Mohave and there are emptier and more desolate places in Providence, Rhode Island.

At any rate, the events in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas could have taken place in any American city during the seventies–and they did, because there were no places then, just blur and drift–just cash transactions, night flights, smoking sections and no airport security. One night in the seventies, I climbed on a little plane to fly from Denver to Aspen. I noticed a songwriter friend of mine curled up in a front row. I stuck out my hand and said it was nice to see him. He made a tiny little wave, and said softly, “Excuse my manners, dude, but I’m just about to die.” I nodded in sympathy and walked past him into the dark plane, quite unaware they he was actually dying, remembering an afternoon in New York when I traded Lowell George’s phone number to a girl in the songwriter’s entourage for a bag of blow. Not my finest hour, although all the girl wanted to do was to fuck Lowell. That night on the plane, I ended up in the back row with two ski bunnies, sharing bumps to the shivering hum of the props in the cold air. When we landed in Aspen, a guy in a chauffeur’s uniform came on board. He lifted my friend out his seat and carried him down to a limo that was waiting on the tarmac. I waved good-bye to the receding taillights, then set off into the swirling, midnight snow after the ski bunnies.

That was the seventies—limos, homos, bimbos, resort communities and cavernous stadiums—the whole culture in a giant, technicolor Cuisenart, whipping by, and I did love it so. Thinking back now, I can’t help but feel that Hunter missed a lot of the stagy grandeur or had no taste for it. He never seemed to have much use for bimbos, or homos, like my songwriter friend, or even for casual romance. I did meet a porn star friend of Hunter’s one night at a dinner in Vail. Her name was Sharon Mitchell and she was a handsome and intelligent woman who now runs an AIDS clinic in Los Angeles. Hunter treated her with the kind of sullen disdain that was what you might expect from a boho snob with a hysterical loathing for working stiffs and service personnel. This remains inexplicable to me to this day. In Hunter’s Vegas book, the waiter at the Polo Lounge is a dwarf; the store clerk is a mongoloid; the room service waiter is a reptile; the lady at check-in is a gorgon, and I hate this. Savaging the weak is not funny, even if you’re purportedly “tripping.” Also, as a matter of journalistic practice, these working stiffs are invariably the sources from whom you get the story, because Lou Reed, for all his candor, is not going to share with a journalist his late night room service order for KY Jelly.

So, finally, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas feels feverish, squirmy, and genuinely afraid of itself. In this book, as elsewhere, one gets the sense that Hunter never really found his place, that he never really got over the La-Di-Da South, the Derby Cocktail Soiree, the Tea Dance and the strut of Southern Manhood. The manners were gone, of course, but the raw, hot, dirt plantation sense of empowerment remained. One night at a wedding in New Orleans, a cultured woman from Thompson’s part of the South, told me how easily she could imagine Hunter a hundred years ago as a Civil War dandy, in his whale-bone corset, his tailored uniform, his flowing locks, his riding crop, his silver flask and his dueling pistols always at the ready to defend his “honor.”

I could never quite make that leap but I could see the puritan do-gooder with a gun, and I can’t help feeling the bleak shadow of puritan revenge in Thomson’s Vegas narrative, during which the author describes himself committing a whole cornucopia of transgressions and felonies. He drives recklessly, wrecks cars, totes guns, drops acid, snorts coke, sniffs ether and smokes ganja. He insults civilians, walks checks, abandons rentals and dodges tabs at fancy hotels. All of these Mister Toad behaviors, I shamefully admit, were pretty much de rigueur for “cultural reporters” in those years. The strange thing is that, for all the crime and bad manners, for all the macho self-aggrandizement, there is no sin in Hunter’s “Sin City,” and, minus sin, Hunter’s Vegas tastes like sucking pennies.

In fact, there is no sex at all in “Fear and Loathing,” nor is there sex in any of Hunter S. Thompson’s writings, no encounters with whores, homos, bimbos, ex-wives, divorcees or members of the wait staff, and this glaring omission profoundly distorts the milieu he purports to portray. In fact, Hunter’s writing repudiates the primary vibe of the zeitgeist, because the post-flower-child seventies, I can assure you, were very, very sexy all the time—even sexier at night and a whole lot sexier in Las Vegas. In those days, one did not go out on the road with Aerosmith or even Hubert Humphrey to huff glue with celebrities. That is a contemporary kink. You went out there to bathe in the dazzled libido of shiny America—to promenade down glimmering streets with crazy girls in torn t-shirts under a blood-red sky—but not Hunter S. Thompson. Hunter hated it all, and this body hate , I suspect, made him the bard of choice for looky-no-touchy, “Less than Zero” America—the era of Post-Sex-Global-Fury—the age of AIDS and herpes, silicone and botox. This makes Thompson prescient, I guess, Jeff Skilling, avant le lettre, arrogant, wasted, drooling and snarling at the waiter. Oh, please, darling.

—

Dave Hickey is a writer of fiction and cultural criticism. He writes a monthly column for Art in America called Revisions and has served as Contributing Editor to The Texas Observer, The Village Voice, Art Issues, Parkett and Context. His work has appeared in Rolling Stone, Art News, Artforum, Interview, Harpers, Vanity Fair, The New York Times and The Los Angeles Times. His published books include PRIOR CONVICTIONS, THE INVISIBLE DRAGON: FOUR ESSAYS ON BEAUTY, AIR GUITAR: ESSAYS ON ART AND DEMOCRACY and STARDUMB. Future publications include CONNOISSEUR OF WAVES: MORE ESSAYS ON ART AND DEMOCRACY, FEINT OF HEART: ESSAYS ON INDIVIDUAL ARTISTS and PAGAN AMERICA. Hickey was recently awarded a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship for 2002-2007 and received a Peabody Award in 2007 for his work as Project Advisor and Associate Producer for Ric Burns’ PBS documentary on Andy Warhol. Hickey presently holds the position of Schaeffer Professor of Modern Letters at the University of Nevada Las Vegas.