— I have always maintained an interest in uncovering photographic works that were neglected, never fully realized, or in need of reinvigoration. Here are three publications, released under PPP Editions, which illustrate this best.

Daido Moriyama, ’71-NY, 2002

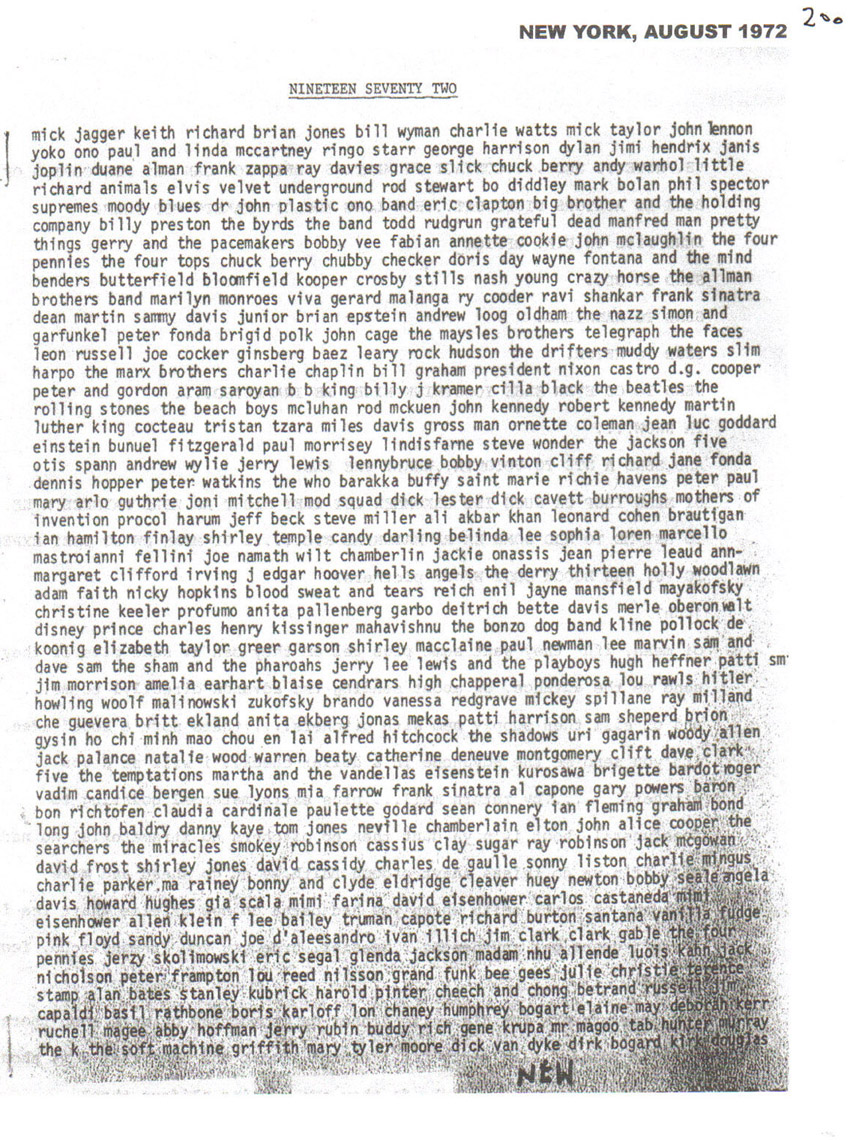

’71-NY (2002) is an expanded version of Another Country in New York, a book Daido Moriyama made in 1974. He brought a Xerox machine into a Tokyo storefront, while outside people would line up to get a copy. Another Country in New York was assembled and staple-bound on location. You could choose from two variant silkscreen covers– a multiple image of the American flag, or an airplane taking off. The Xeroxes within were made from photographs that Moriyama shot during a one-month visit to New York City in 1971 — the first trip he made abroad. There were under 75 images reproduced in the original book, and at most 100 copies were sold.

Upon meeting Moriyama for the first time in Tokyo in 2000, I inquired about the remaining images he shot during his visit to New York. He told me they were still in negative form. There were over 50 rolls of half-frame film, at 72 images to a roll and no existing contact prints. I asked if he would consider allowing me to publish a book of photographs from the unpublished images; he agreed. A month later I received the contact sheets with Moriyama’s selections circled in yellow. I then went through them and circled in red the images I liked and sent them back. Shortly after, Moriyama sent over 200 photographs to reproduce in the book and to my surprise he turned the entire project over to me — asking me to make the book I wanted to and to send him a copy when it was complete.

I felt the only way to approach an edit of such a large quantity of images was to try and recreate Moriyama’s original experience — from the airplane to nearing the city, to being in the hotel, on the streets, during the day, at night, alone. While the title of the original Xerox book referenced James Baldwin’s classic Another Country (1962) — the painful life and eventual suicide of an overly sensitive, young African American man in New York City — for our expanded version I chose’71-NY from a marking that appeared on the contact sheets. I incorporated in the book a bilingual interview I had made with Moriyama about the original Xerox project, along with an excerpt from Baldwin’s Another Country, a commissioned essay on Moriyama’s photographs by Neville Wakefield, a selection of the original contact sheets with our markings on them and lastly, at the opening of the book, a facsimile letter Moriyama sent thanking me for making the book and giving him the opportunity to revisit the intensity of that time in New York.

I also wanted ’71-NY to reference For A Language To Come, a critical photographic book from the 70s by Nakahira Takuma, a close friend and colleague of Moriyama’s and one of the founding members of Provoke. For A Language To Come has a colorful, pop dust jacket while the book itself prints a somber black and white photograph that spans both front and back covers. I was always attracted to this kind of contrast between the jacket and what is hidden beneath, so for ’71-NY I illustrated the cover with vivid blue and white stripes while keeping the entire exterior jacket solid black except for two dye-cut elliptical holes that reveal the underlying stripes like searchlights in the night.

Although ’71-NY is a small chunk of a book, most every double-spread bleeds a single image at close to its original size. To read the vertical images the book must be turned on it’s side, a tradition in Japanese photographic books. There is no text on the jacket, cover or spine. Instead the title of the book, along with the PPP imprint, appears in white type on the spine and cover of a traditional Japanese, corrugated-cardboard slipcase — a carefully orchestrated package.

David Wojnarowicz, RIMBAUD IN NEW YORK, 2004

Rimbaud in New York (2004) is one of my favorite projects. It began with a question posed by the collector Philip Aarons, “What do you know about this series Wojnarowicz made in the late 70s?”

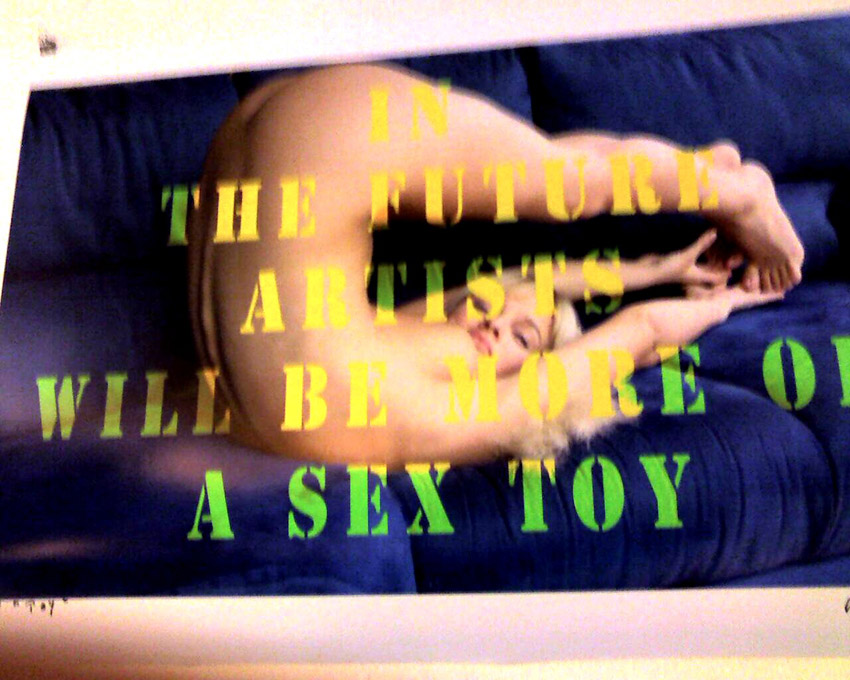

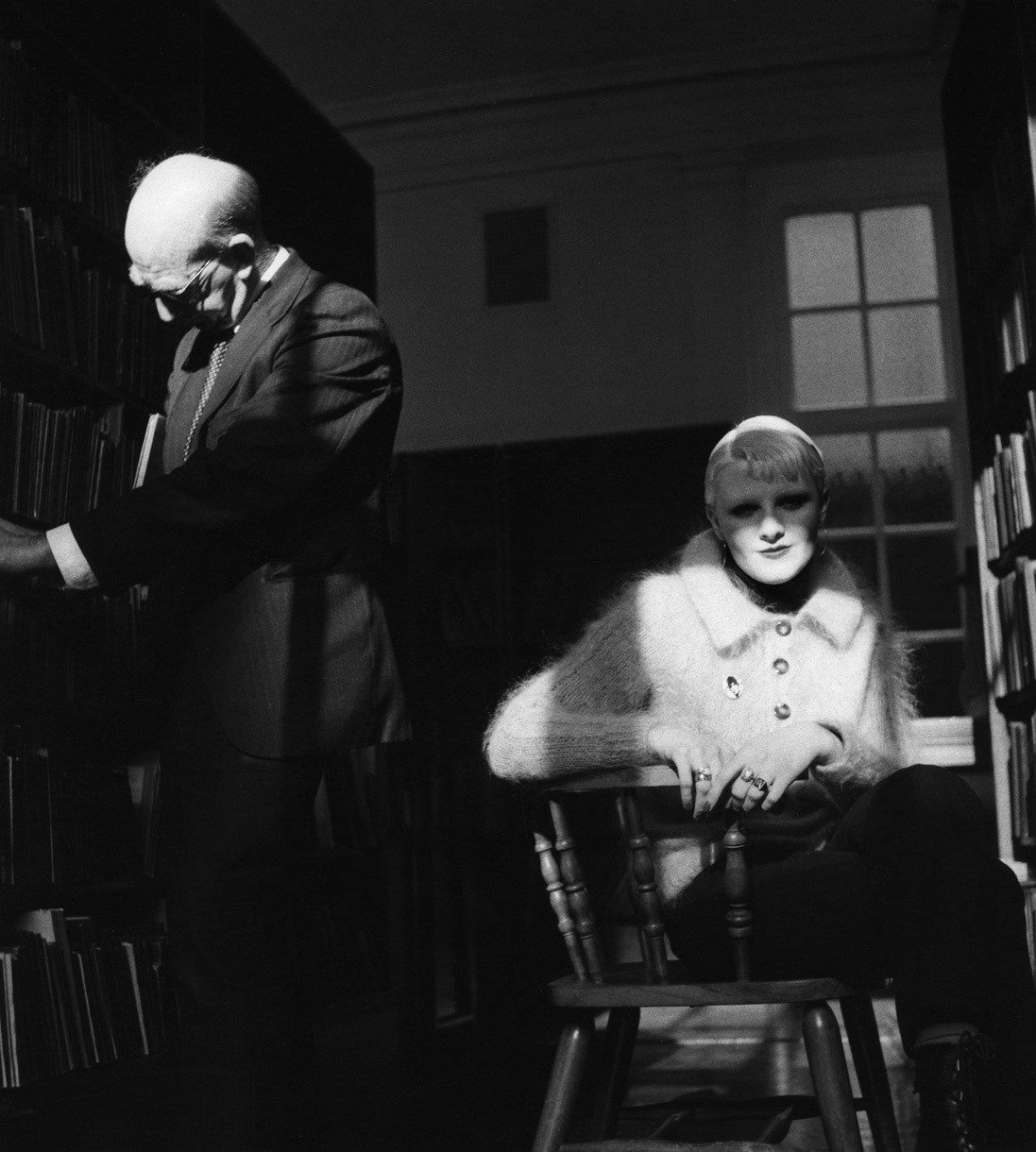

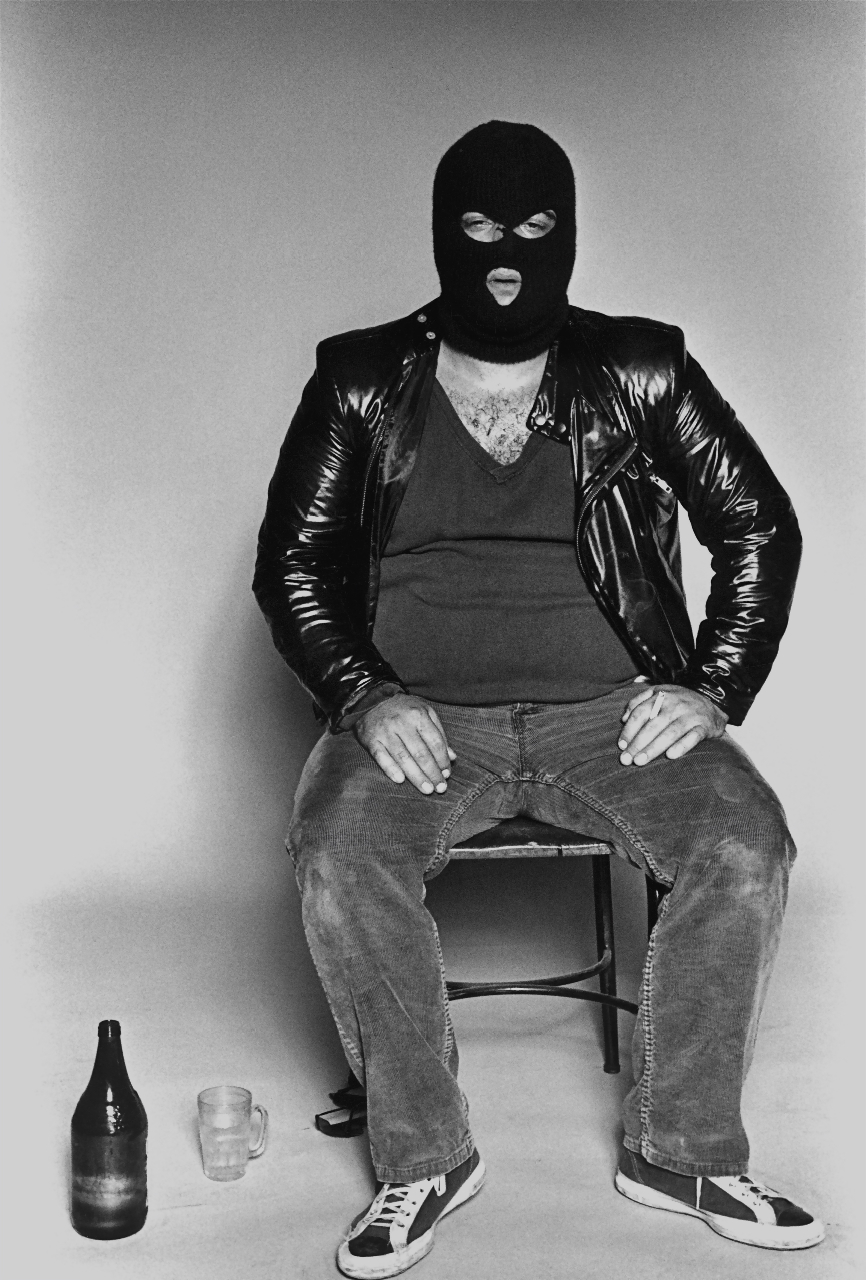

From 1978-79 Wojnarowicz produced a quantity of black-and-white photographs of a young man, posing as himself, wearing a mask with a reproduction of a portrait that Etienne Carjat had taken in the late Nineteenth Century of Arthur Rimbaud. Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud is viewed in locations and situations, both private and public, around Manhattan. Selections of these images had been published in journals and newspapers throughout the late 70s and 80s, but they were never fully realized as a series until 1990. Two years before Wojnarowicz’s death he selected twenty-five negatives and produced a portfolio of 8 x 10 inch prints in a proposed edition of three. He only realized one complete set; the individual prints were sold separately and traded infrequently in the market.

When I visited the Fales Library at NYU where Wojnarowicz’s archive is housed, I looked at and read everything — negatives, prints, diaries, correspondence, and sketchbooks. I realized that Rimbaud in New York, although created early in his career, was a critically important work for Wojnarowicz and in fact there were many more compelling photographs from the series besides the mere twenty-five Wojnarowicz had previously selected. With the assistance of Tom Rauffenbart, Wojnarowicz’s surviving lover and the executor of his estate and his dealers at PPOW, Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pinkleton, I took on the task of reconstructing Rimbaud in New York.

Some of the negatives from the original series were lost; others, from the larger body of work existed only as negatives; still others, merely as contact prints. We had to make new negatives from a hand full of early prints we located and in a few cases, new negatives from contact prints. The master print-technician Charles Griffin was instrumental in seamlessly fabricating the images to match the look of the prints from the original portfolio. I poured through these new photographs and culled a group of sixty-five that had potential, together we narrowed our selection to forty-four. These were editioned in a new portfolio of 11 x 14 inch photographs, which set them apart from the original 8 x 10s and became the raw material for our book.

Wojnarowicz was very versatile as a photographer and was comfortable shooting both vertical and horizontal images. This made it especially challenging to sequence and organize his pictures in a book format. I decided on a portrait-oriented book, presenting the vertical images as full bleeds on one side of a double-spread and the horizontals spanning the gutter and bleeding off either the left or right side, leaving a bold white margin. This layout maintains an active rhythm and presents a quasi-diaristic account of Rimbaud’s life in the city. The book opens and closes with drawings Wojnarowicz made of Rimbaud masturbating. Upfront there appears several pages from Wojnarowicz’s diaries, one showing photo-booth strips of him with the mask on posing with a gun in his hand. I wanted to transform the book into that mask, so I printed the front of the mask on the front cover and the back of the mask on the back cover, with no text on either side.

For the main text I commissioned Jim Lewis, as I specifically did not want a queer writer, no competition for Wojnarowicz’s iconography or personality. I also wanted fiction, not an essay.

Your head turns away: O the new love! Your head turns back: O the new love!

This is a fantasy, an imagined meeting between a ghost from the time before the AIDS epidemic and a contemporary young man in the street. In addition Tom Rauffenbart presents an account of his first meeting with Wojnarowicz — his perception of him as a lonely man and his insights into the Rimbaud photographs. The book ends with a statement I wrote about the making of the book itself and how the project had unfolded.

Keizo Kitajima, BACK TO OKINAWA 1980/2009, 2009

Back To Okinawa 1980/2009 (2009) is my most recent book. It is a new version of Keizo Kitajima’s serialized, 4-volume publication Photo Express Okinawa (1980). The original self-published books were scheduled for release every other month, over one year, though only 4 volumes were ever realized. Together these 4 volumes form one work — an investigation into the nightlife in Kozu, the red-light district surrounding the Kadena Airforce Base in Okinawa. Kitajima immersed himself in the life of Okinawa’s nightclubs, bars and streets, photographing a mix of American military (chiefly African-Americans), Japanese prostitutes and drag queens.

The original volumes are extremely difficult to procure as a complete set, though they don’t amount to much — 4 slim, 16-page magazines with images of varying sizes bled across each double-spread and onto the covers. They are numbered consecutively and dated by month, along with the exact period of time in which the images were shot, as in 1.1-15. The typography on the covers are printed in vibrant 80s colors but the content is inked up with extreme black-and-white contrast.

I finally found and bought a set from a private auction in Tokyo last year and got in touch with Kitajima to propose republishing the book and making an exhibition. Regrettably, absolutely nothing from that work survived, not the photographs, not the negatives. Kitajima did not even hold in his possession a set of the original 4-volumes. Still he agreed to the project, even though he had nothing to offer! I decided to make the new book by scanning the photographs printed in the original volumes, even those that crossed the gutter — these I had to have digitally repaired. The images are printed on tabloid-size newsprint stock, the covers are screen-printed and then bound by hand-sewn black thread.

Back To Okinawa 1980/2009 reproduces every image from the original volumes in four separate sections, though re-edited. The images still bleed into one another — often across the gutter, hovering in the center of the sheet; they never touch the edge of the page, appearing as puzzle pieces. The silkscreen image on the cover — a street scene from Okinawa at dusk — is reproduced from the original volume #4 and does not repeat in the body of the book. This way the cover is integrated into the sequence of images within. Back To Okinawa tips its hat to Moriyama’s Another Country in New York.

Andrew Roth

—

Andrew Roth specializes in selling rare photographic and artist’s books from the 20th century, while also publishing limited edition books himself under his imprint PPP Editions. He maintains a gallery in a New York primarily exhibiting the work of photographic artist’s from the 60s and 70s, as well as contemporary art. Over the past 10 years he has presented exhibitions by key Japanese artists Makoto Aida, Nobuyoshi Araki, Ishiuchi Miyako, Daido Moriyama, Shomei Tomatsu, Tadanori Yokoo, and most recently, Keizo Kitajima. Along with exhibitions on the work of Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Robert Heinecken, Ed Ruscha, Collier Schorr and David Wojnarowicz. In 1999 he presented PROVOKE, the first exhibition in the US to outline a critical history of rare Japanese photographic books. In 2001 he published THE BOOK OF 101 BOOKS — a primer on the history of the photographic book, which went on to help define the rare photographic book market of today. Recent publications include; Larry Clark’s PUNK PICASSO, Leigh Ledare’s PRETEND YOU’RE ACTUALLY ALIVE and MALE: FROM THE COLLECTION OF VINCE ALETTI. Forthcoming from PPP Editions is a fully illustrated, 450-page reference book IN NUMBERS: SERIAL PUBLICATIONS BY ARTISTS SINCE 1955.

andrewroth.com