KELLY REICHARDT

Friday, June 22nd, 2012— I grew up in Miami in the 1970s. My father used to come home early in the mornings after a long night of overtime, unclip the holster from his belt, pour himself a tall glass of milk and say, “Ah crime pays.” My mom carried her holster in her purse and in a pinch was as likely to pull out a ratty hairbrush as a 38. My dad worked the midnight shift. His car had Dade Country Crime Scene painted on the sides. My mom was an undercover narcotics agent and always had a different car – ones that were non-descript and which apparently you were not supposed to transport children in. I know this because my sister and I did a lot of crouching on the floor when we would enter certain parking lots. We would stay hunched over- mind you I was probably three feet tall at the time and my hunching was unnecessary- and move quickly into our own car where we again would lay low until we were outside the parking lot. Suitcases might appear from a trunk and be moved to another waiting car. Despite my parents line of work, despite the influx of Cuban exiles and boatloads of Haitian refugees floating up on the shores and despite Miami being the murder capital of the country – it seemed a pretty dull place to grow up. I remember Thurston Moore recalling when he was visiting Miami in those years, seeing an ad in the Herald that said, “if anyone has heard of The Clash, please call me”. That really gets across the isolation and general feeling of being a teenager in an endless string of sunny days in a city of retired people.

Through out the late 60s and all through the 70s, I spent a lot of time on Miami Beach – first with my grandparents and later as a teenager taking my first photos. Somewhere in the early 80’s, having secured a job at Peaches Records and Tapes, I quit The Clog Shop on 163rd street and dropped out of high school. I was no longer living at either of my parent’s houses (they divorced when I was eight) but was bouncing around between my friend’s parents houses, my grandmother’s condo in a retirement village and pretty much blowing it in every situation I landed. The order of things gets a little foggy here but I did get my GED and enrolled in Miami Dade Community College. I got a little apartment in North Miami for a brief spell and through all the haze and chaos of those years I continued to photograph Miami Beach. Then, encouraged by the sixteen dollars I won in the Miami Dade Community College photography contest, I headed north.

I had gotten a ride to Boston and was staying at a friend’s apartment. I experienced my first snow and randomly met a bunch of punker art-school kids. They seemed to have it all going on. Thrift store dresses, army boots and shaved heads. I had no idea how old they were, I had no idea what punks were, they just seemed to be from mars (as it turned out they were from Martha’s Vineyard and weren’t actually very punk in their musical taste but more into records like The English Beat and Rock-a-Billy tunes by the Collins Kids) All my life I had suspected cool shit was going on all over the place if you could just get yourself north of Tallahassee and it was all proving true. I knew these kids (if they even were kids) were better educated, more cultured, and just generally better for having grown up someplace other than Florida. Within a week of being in Boston I enrolled in night classes at Mass Art and when I was invited to flop on a couple of the art-school kids couch, I was so totally fearful of them seeing my corny Miami photos that I destroyed them all. I remember tearing them up and throwing them in a dumpster on my way to buy some plaid trousers. I felt a real need to disassociate myself with all things Miami especially since the old timers and the Mahjong scene was being quickly replaced by Miami Vice, body builders and super tanned rollerbladers.

I can’t recall exactly where I first discovered Andy Sweet’s photos but it wasn’t long after moving north, probably in some bookstore in Boston. In any case, seeing images of Miami Beach in a different context had a real effect. I can still conjure up the physical pain I got in my gut. Seeing Sweet’s photographs outside the glare of Miami, I realized that my own photos were probably, some of them at least, possibly pretty ok, maybe even good. They were at the very least pictures of a unique time and place that was already fading away. If only, back when I was out there on Ocean Drive, with my Pentax K-1000 – If only I could have stumbled into Andy Sweet’s photographs or for that matter Stephen Shore’s. Even if I had just seen some little bit of good art as a kid I think I could have had a whole different experience. If I had met anyone, just any one person along the way that had heard of The Clash those years could have all been so different.

Andy Sweet was murdered in 1982 in the City of Miami Beach in The Carmel Villas Apartment Complex. He was stabbed 29 times. Approximately 99 color photographs were taken from the scene. My dad sent me a copy of the crime scene report; blood splatters run at a 45 degree angle, two ashtrays are over turned, there is a wooden box on the bed, TV is tuned to channel 7…

Twenty years after Sweet’s murder a local storage facility lost all the negatives of his work. His parents rented the space which advertised “Museum Quality Storage” for 10 years, paying the $25 a month fee until they received a notice alerting them that the five boxes of negatives could not be located. The Sweet family was paid $1 per box in keeping with the agreement they signed in 1992.

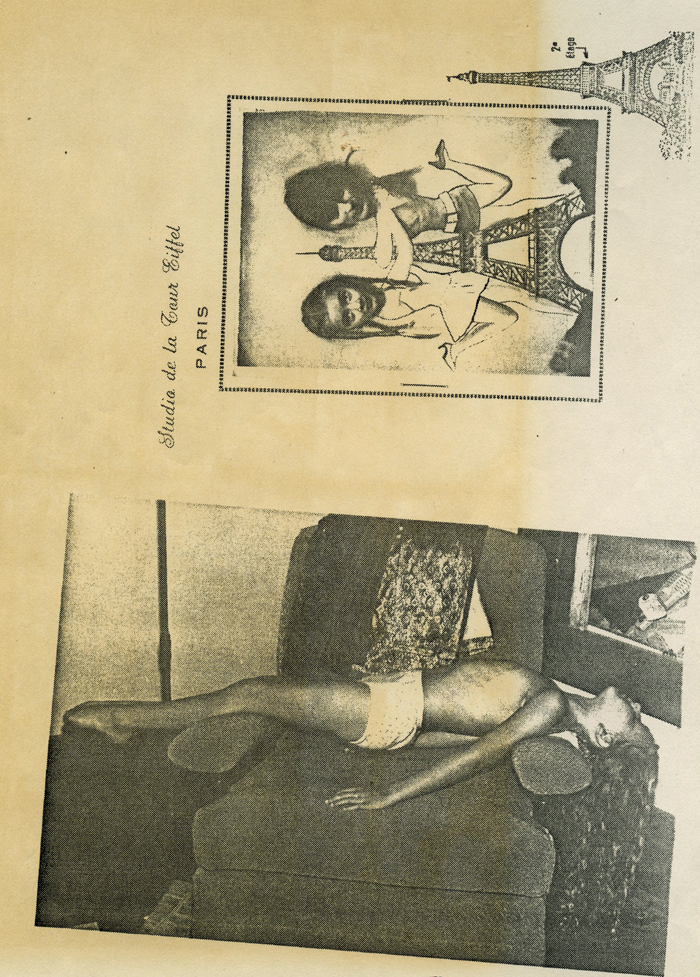

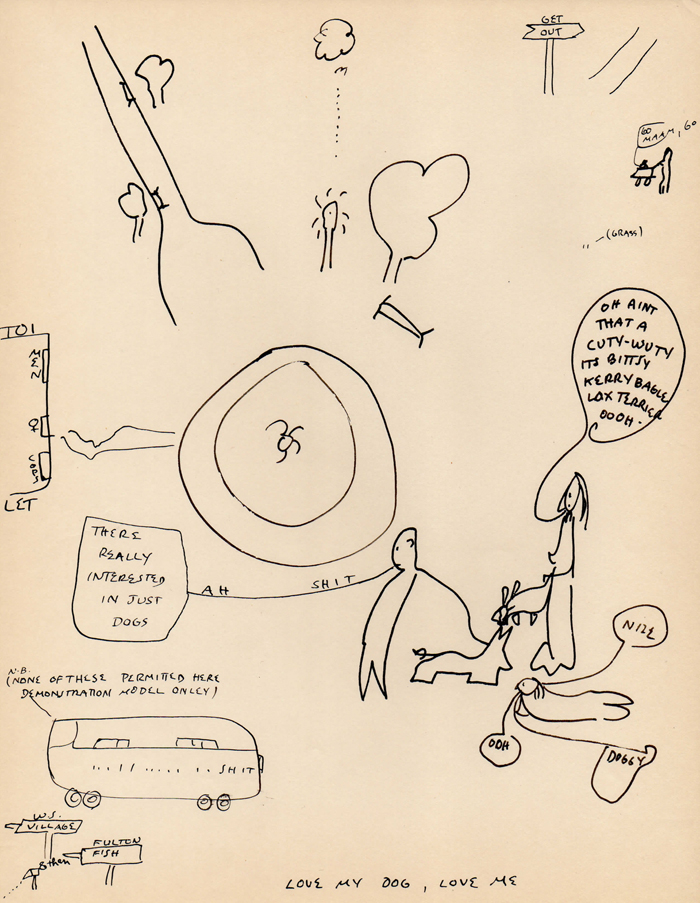

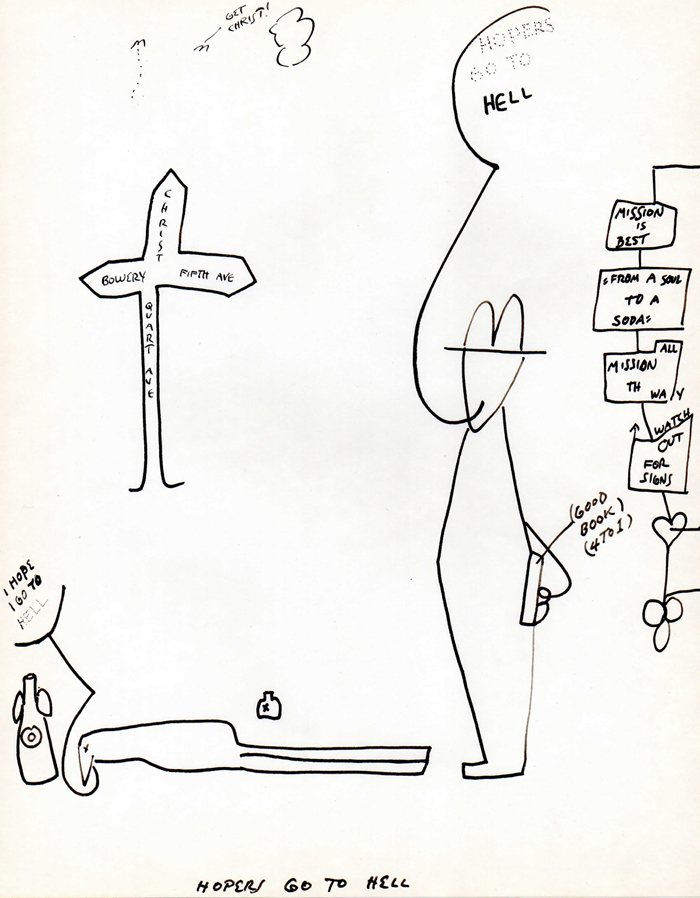

After you get some distance from a place, you realize there were some things you liked after all. And one of those things for me was the Miami Beach that is represented in Sweet’s photography. These photos come from the now out-of-print book entitled MIAMI BEACH.

Kelly Reichardt was born in 1964 in Miami, Florida. She lives and works in New York City. Her feature debut RIVER OF GRASS (1994) was acknowledged at many international festivals. Her second feature, OLD JOY (2006), won a Tiger Award at the 2007 Rotterdam Festival. WENDY AND LUCY (2008) had its premiere in Cannes and her most recent film, MEEKS CUTOFF (2010), premiered as part of the Official Section at Venice Film Festival. In the 2012 her work was included in the Whitney Biennial. Reichardt is currently Artist-in-Residence in Film and Electronic Arts at Bard College, New York.