The phone rang early that morning. The landline phone was on the floor next to the bed. His father jumped up immediately. He had been waiting anxiously all night for that phone call. His mother sat up after him. Through the mosquito net she looked at his back while he picked up the phone. The call lasted less than 10 seconds, for the information was brief and predictable: “Father is dying. Come quick!”

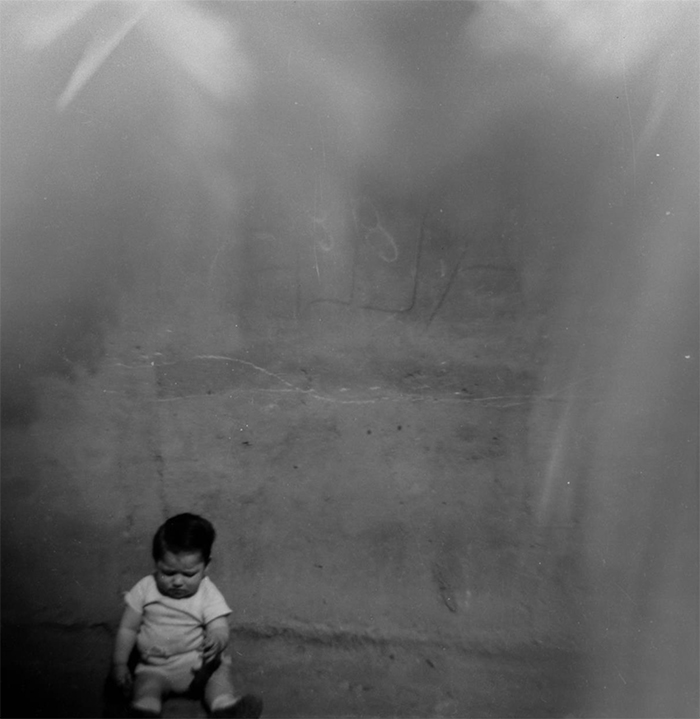

His grandfather was a distant man. He was absent most of the time during his childhood as much as his father’s. He remembered his naked silhouette standing in the bathroom, water splashing. The floor was evenly cemented and there was a small open window high up. His grandfather had many secrets, for he had many mistresses. His grandmother had given up holding on to him. Cleanliness was her constant concern, she changed clean clothes every day, and making a jealous scene was for her unclean. She pretended nothing had happened every time he returned home in disgrace after being dumped. She still cooked (three meals a day, three dishes per meal), washed his clothes and hers (by hand) every morning, mopped the floor (by hand) at least once a day. She served him without a word of condemnation, having left the condemnation to his own conscience. But each time, before she could be satisfied with her move, he disappeared: he came back to the one who had just dumped him, or to someone else, or maybe he just ran away from the silent punishment at home.

He now lay motionless on the wooden divan. His breaths were intermittent. He had been diabetic for several years. When it got worse, he came back home to his wife (caretaker). Someone placed next to his ear a cassette player, playing the Amida sutra at low volume. Everyone had accepted that he would soon die, and the chanting sound helped him depart peacefully. What did his grandfather see between his intermittent breaths? A couple, the same age as him, appeared at the front gate, each holding a pack of incense and a bouquet of gladiolus (flowers for the dead). When the couple learned that their friend was dying and not yet (completely) dead, they felt extremely embarrassed, apologized for their misunderstanding, quickly threw away their offerings. When he came home from the morning class, he saw that his grandfather’s face was covered by a piece of paper ripped from a student notebook. Next to his ear, there was no longer the cassette player, but a long knife.

The wooden divan lied next to the entrance door, where the wind slipped in through the gaps. Sometimes the paper on his face breathed in and out slightly.

His grandparents’ house stood at the top of a steep slope. The road leading up to it was just wide enough for two scooters to pass at the same time. On one side of the slope were the rows of house roofs below. Once he and his cousins blocked the door gaps with clothes and rags, opened all the taps so that the water flooded the whole house. Then they slid up and down, splashed the water, soaked their bodies and swam on the floor. When their grandmother came back, they all hid under the bed. She said nothing, went to a hedge nearby, broke off a long branch and plucked off all the leaves. With the stick in her hand, she sat beside the bed and called each of them out. They only pretended to be afraid.

The second time the house became a chaos was when his grandmother and grandfather had the biggest fight. That was the first time he saw his grandmother let out her anger. She threw and broke everything that was within the extension of her hands: bowls and plates, pots and pans, cups and glasses, tables and chairs, papers and newspapers… No longer water, the house was flooded with the shards of an endured marriage. A moment later she cleaned up the house. Nobody helped her.

In the kitchen, his mother and aunts gathered to prepare food and offerings for the funeral. They talked about what each of them should do in the next few days. They all seemed to be shy about wearing the funeral costume. One of his aunts said as if to comfort herself: “Well, we don’t get a chance to wear it every day.” His father was the host of the funeral. Besides wearing the white muslin shirt and trousers like everyone else, his father wore a white muslin hat with a straw rope wrapped around his head and held a long bamboo stick in his hands. With the special costume, the visitors, even if they did not know him, knew that the man standing in front of the coffin and bowing to the visitors was the eldest son of the deceased. The old couple returned with a new packet of incense and a new bouquet of gladiolus.

The wooden coffin, painted gold and polished on the outside, stood in the middle of the living room opposite the entrance door. His grandfather lay in that golden box. He couldn’t remember how he was dressed because he didn’t dare glance at him. Years later, what he would remember most about his face was when it was covered by the white paper. The funeral lasted three or four days. Usually at a funeral, a band of musicians played day and night. But his grandmother did not like to bother the neighbors, so she omitted that ritual. At night, the clearest sounds were the chanting on the cassette player and the cracking of melon seeds between the teeth of the visitors and his family.

On the first day of the funeral, he had to go to school to hand in the application for leave. Having failed to find a normal blue or black pen, his father wrote and signed the application with a green pen. It took him only 15 minutes to cycle to his school. He deliberately wore the funeral costume. When he entered the class, his classmates were all leaning their heads on their notebooks and writing something. Everyone looked up at him in bewilderment. The teacher, who was grumpy every day, gently accepted his envelope and let him go. The white scarf wrapped around his head had convinced her much more than his father’s squiggly green letters. That day, he felt a little proud to be the only one of his classmates who had the chance to wear such a costume.

The staff from the funeral home poured dried green tea leaves into the coffin. With their hands, they filled the space between his grandfather’s body and the coffin walls with tea. He smelled a faint fragrance. They closed the coffin and hammered nails into the rim (fortunately his grandfather was truly dead, who would hear his cries for help had he resurrected?). The sound of the nails hammered into the coffin had a strange spiritual force, causing everyone to suddenly burst into tears, rush to the coffin and try to touch it with their hands. Some tried to outdo the crying of the others.

An obituary customarily ended with the following sentence: “In this moment of confusion, please forgive the bereaved family for any mistake.” Confusion. Who wouldn’t be confused by the death (of a family member)? The most difficult question for his father was, “How to start?” There were so many things to prepare, to buy. There were many unknown rituals to follow. Who should he inform of the news? Where to find a coffin? What kind of coffin (and the price)? Which monks should be asked to come and do the chanting? What would be the right time to go to the cemetery? Funeral homes operated on the mechanism of confusion. The family didn’t have to do much, they just needed to confuse and be confused. The services took care of the rest. But the extent of this care depended on the package chosen.

Like their house, his grandfather’s tomb also stood on a hillside. The cemetery had one of the best views in the city. It was quiet. The rows of pointy tomb roofs aligned all the way downhill. At the hill foot was the area for newborns: small nameless graves. Some tombs, enormously and extravagantly built, with steel gates guarded by snarling stone lions, belonged to the dead rich in the eternal realm where a clock was handless. His grandfather’s tomb was an average one, like most. Sitting by the tomb, he could see small human figures farming the banana, pepper or coffee gardens on the hills opposite. As far as his eyes could see, there was a gigantic mountain range over the horizon. He preferred to think that blurry mountain was a dam that would protect this city and this cemetery from a deluge.

Right next to his grandfather’s tomb was a lot with an empty grave pit. The pit was sealed with concrete and could easily be opened in due course. The lot had been bought for his grandmother.

He still feared every time he heard the phone ring early in the morning. Was it not that death always came with-in a phone call? “Are you the mother/father/husband/wife of X? I’m sorry, X is …” His grandfather’s passing was the closest encounter, nose to nose, between his father and death. Writing the application in green ink showed how lost and confused his father was. Soon it would be his turn. What had he done to prepare for this? He didn’t want to be confused, but he couldn’t be sure that he wouldn’t write in green ink when the day came.

By chance he saw his birth certificate (certified) copy. The yellowish paper with the worn-out edges grew so thin that one could see through it. It said on the paper:

Surname and first name: X | Male or Female: Male | Date of birth: MM-DD-YYYY | Place of birth: Medical Post of ward A, B town | Ethnicity: K |

There was a frame with the information about the parents:

Mother’s surname and first name: Y. Occupation: housewife | Father’s surname and first name: Z. Occupation: mechanic |

Reading this certificate reminded him of how reluctant he was every time he had to fill in the ‘Place of birth’ section on administrative documents. Where was his birthplace? ‘Place’ here meant a specific location: that small medical post (no longer existed)? Or was it a geographical space: the town of B (as well as this country)? And he could easily write that his birthplace was on the clinic bed. What about place of death? Where was his grandfather’s deathplace? This town? Or the house? Or the wooden divan?

In 2020 and 2021, funerals took place on Zoom. Technically, everything on the screen was streamed live, but again, technically, the images were always delayed, even if only by a few hundredths of a second, and when the connection was weak, the images froze and slowed down. Relatives and friends attending the deceased’s funeral on Zoom were, to a certain extent, watching archive footage. Did this distance in space and time lessen the pain?

To mark its 50th anniversary, Doctors Without Borders displayed a large poster in bustling public places: Hundreds of makeshift tents crammed onto a patch of land somewhere in Nigeria, a group of women and children standing in the foreground, some looking at the camera; blocking the horizon was a slogan half the size of the whole poster, printed boldly in red: WHEN WE SUFFER FAR, DO WE SUFFER LESS?

In 2022, those in Switzerland who wished to have euthanasia had the choice to use a capsule machine instead of medication. Below were the (rephrased) quotes from the inventor of the machine:

“The machine can be towed anywhere for the death.

The capsule is sitting on a piece of equipment that

will flood the interior with nitrogen,

rapidly reducing

the oxygen level to 1 per cent from 21 per cent in about 30 seconds.

The person will feel a little disoriented

and

may feel slightly euphoric

before

they lose

consciousness.

Death takes place

through

hypoxia and hypocapnia,

oxygen and carbon dioxide deprivation,

respectively.

There is no panic,

no choking feeling.

The person will get into the capsule

and lie

down.

It’s very comfortable.

They will be asked a number of questions

and

when they have answered,

they may

press

the button

inside

the capsule

activating

the mechanism

in

their

own

time.”

—

Trương Minh Quý was born in Buon Ma Thuot, a small city in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. Quý lives and works here and there in the vibrancy of memories and present moments, his narratives and images, lying between documentary and fiction, personal and impersonal, draw on the landscape of his homeland, childhood memories, and the historical context of Vietnam. His films have screened at Locarno, Berlinale, New York, Clermont-Ferrand, Oberhausen, Rotterdam, among others.