13th April 2020

Dear Sabrina,

Here’s the story I wrote for you. Don’t tell me I don’t do anything for you.

(Didn’t Seth Price get some hot cha-ching for writing a second-rate story? Fuck Seth Price)

Cleo

4:48 Psychosis

I had a friend who I liked to tell what I really thought about things–or people–mostly people who were disgustingly enthusiastic about life and around whom I immediately felt superior. Maybe because it seemed like most of the time she’d agree, and if not agree, at least understand. She was the kind of girl who looked like she didn’t sweat. I could be wrong. She told me I had a large head for a skinny person, like a greyhound or Chupa Chup, so there’s obviously something missing in her, and unquestionably me: faulty brain synapses perhaps from our 4-year bout with alcoholism, but it’s because of this that neither of us noticed. To me, this gave her credibility. I was jealous of her sunny Los Angeles; it gave her an advantage in life, all that vitamin d, botox, favors from Silicon Valley, superfoods, and anorexia. But it was also true that Berlin had abbreviated itself over the past several years; Gorlitzer Park’s speed-pushers, weed dealers, patchouli, and vigilante’s had been nudged out by yellow unisex visors and frisbees, kites and seagulls. Which is to say: good riddance, Berlin drumming circles. I despised being in circles just generally, in the middle of them, on the edge of them, all of it. I hated introducing myself in theatres of the round with declarations of nationality and one fun fact because my idea of fun fact is to others, personal atrophy.

It’d been a busy week for her, ticking non-gendered or full-blooded Sioux boxes on art funding applications so she’d have the marginalized advantage; she was a fraud, and I was pretty supportive of it. That type of forgery makes people way less judgmental and puts me at ease with my own secret revelations; few people won’t judge you for pasting fake tattoos in nautical themes on your three-month-old newborn, and equally reassuring is knowing there are other people on earth as shitty as you. She didn’t know about a lot of things, pre-fab houses, for example, or confessional booths, or dangerous wildlife: things I knew a lot about.

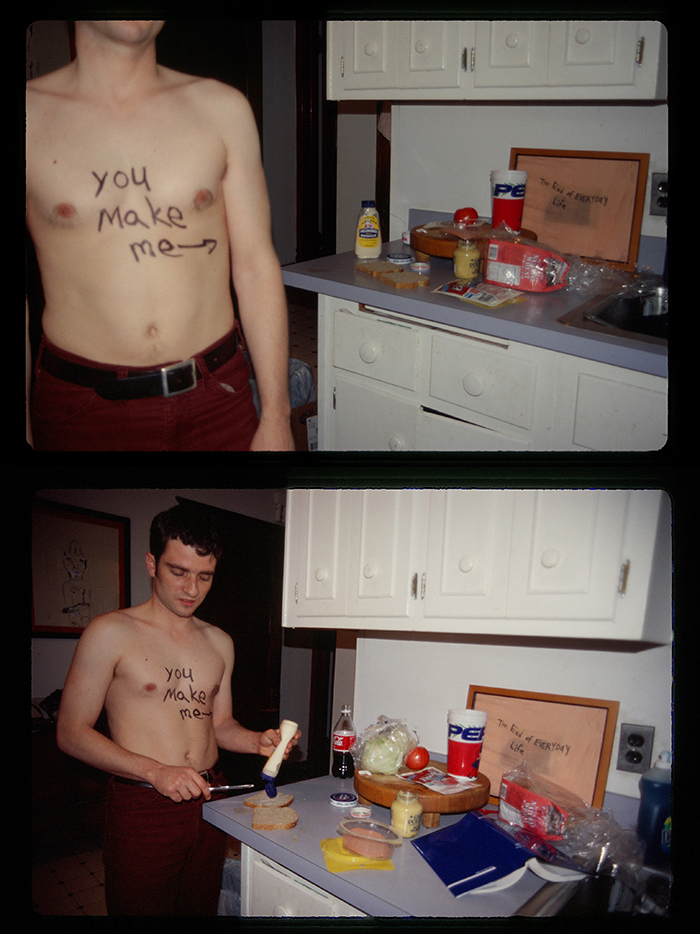

I told her I was writing a new book with nine short essays, an ode to Salinger I told her, before admitting nine was just a modest number and I’d relinquished delusional ambition some time ago– around the time I realized I didn’t have any specific talent in life, mostly just the ability to make small nods to people that had actual talent. I didn’t mind. I had lots of ideas for career paths that I floated by her. Confused aspirations but still, solid options: private eye, sous chef, porn star, navy seal, career jobseeker on benefits, but I guess that’s basically the same as an artist. She didn’t have a shred of sanity, so I knew she’d humor me and my half-baked ideas. We’d toast to almost everything.

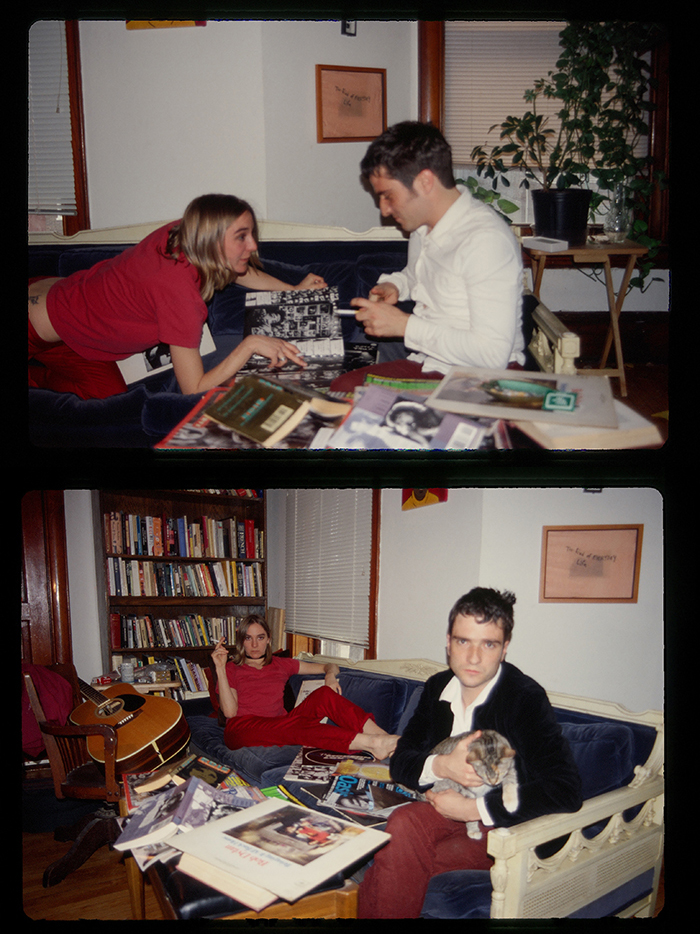

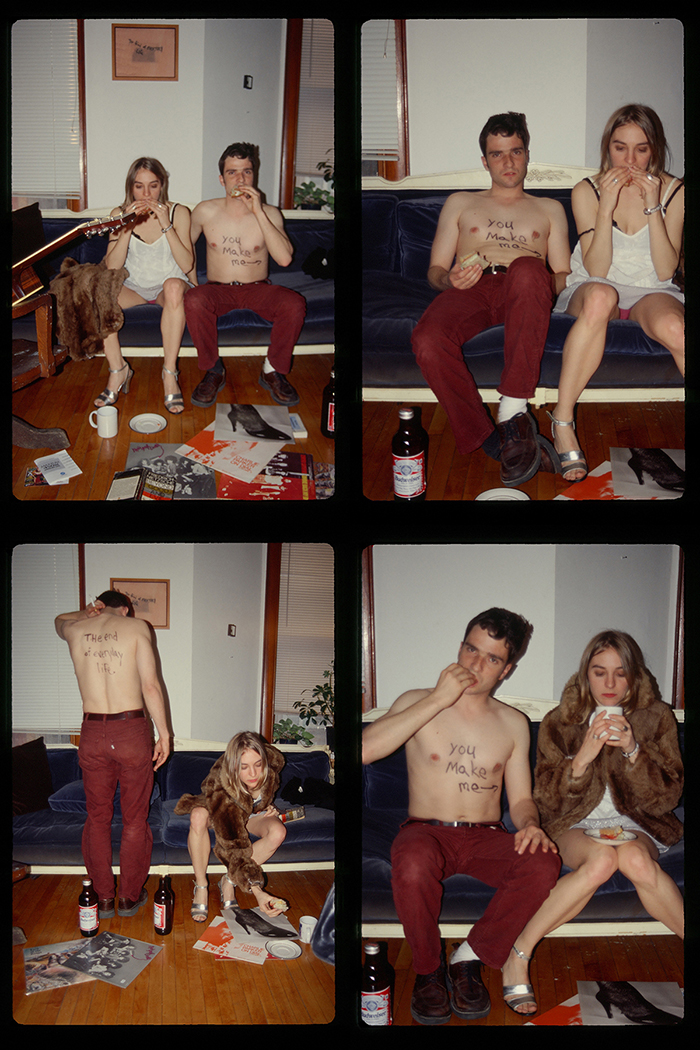

It was a Tuesday night when she rang, Arthur Russel’s ‘A Little Lost’ playing in the background, which always reminded me of the time I slept with my boyfriend’s friend in Copenhagen, then tried to cover it up. My childhood nemesis called me a slut every day for years, even when I was a virgin, so I figured since I had the reputation, I should make the most of it. I would’ve been pretty happy to take it to the grave, but Zuckerburg double-crossed me. I’ve since gotten over it—the Zuckerburg bit, not the cover-up. A moment later, she’d sprung into action. It was over Skype, so I saw her leave the room looking cute in a golden Dolce and Gabbana dress worth a cool 3k she’d scored for $40, not because she paid for it, just the cost of the Uber getaway all the way back to Pasadena. She disappeared for a good twelve minutes, came back without justifying her absence, and started talking–to herself more than me, but I had Pringles, so I didn’t really mind. I listened through crunches of salt n’ vinegar, missing a third or maybe half of what she said; it was an uncivilized hour in Berlin, but it wasn’t accounted for in the conversation, which required stacks of concentration and a nimble leap from salt n’ vinegar pringles to soft, and then hard liquor. She was deep in the dumps writing a diary entry for Artforum without getting any kudos for it, a ghost (blow)job for an artist who wanted the authorship credit and an editor who didn’t mind–an ethical merry-go-round hard to get off in the art world. Luckily, she was the daughter of a street light and cinnamon bun, which is to say she was sweet but harsh and confronted people easily, which went a long way in the art world. She said something to the editor like, ‘If I die and my name isn’t in there, I’m going to be really angry, and if I die and my name is in there, I’m going to be really angry, just not at you.” Her ethics were impeccable, but then again, your ethics don’t actually matter when you’re hot and a genius. She was a genius, sure, but I was ingenious (though my friends called it Machiavellian), so I had more experience getting what I wanted in ways that were unconventional… which is why she called me in the first place.

She was ‘privileged’ the task of applying for sizable funding to pay related costs to review the FIAC Art Fair–flights, crack motel, haircut, retinol, money to research the article, to write the article, then scratch out her face in the photograph. The artist getting the credit was also a tenured professor at CUNY with 76 articles and 6 books to his name that his research assistants wrote on smart drugs like Modafinil from their nine-person share-house in Skid Row. It was a routine story in the art world so I could multitask, loads of tabs open on my computer, shopping for Majesty Palms online, buying books by Donna Haraway, researching dictionary meanings for words in books by Donna Haraway. While she made good points, I watched her flatmate Keke float around in the background looking ill but sexy, like a picture of a serial killer on his deathbed–it was one of the reasons I started the pen-pal program at San Quentin. Life: I was obviously not in command of the situation.

In addition to ethical issues, hers was a cash-flow problem since the tenured academic and his combustible hairdo would get the favored percentage of the agreed-upon fee, and she the remnant, which was probably just enough to reimburse that Uber ride. She had his contact details saved in her phone as dial-a-god but wasn’t terribly committed to answering the lord. The professor was attached to his phone, tuned into his ringtone like it was his son since his underlings were scoring him hot authorships and publications in A+ peer-reviewed’s and modest returns from all the art crits his name had been commissioned, which I guess was his side gig and kept his readership broad. I took a covert screenshot of our Skype call; maybe I’d make an artwork out of it. Keke would be the surprising ghost you sometimes find in the background of photos, a talky background ghost, kvetching his crummy existence in some cringy Los Angelian vernacular I couldn’t know. I tuned him out at gnarly or any other street slang that ruined his sexy serial-killer vibes and watched him eat a pricey grapefruit like the surveillance camera that I was. He was studying supernovae and neutron stars at UCLA, though I was yet to understand how that was going to be useful. Keke wasn’t in our conversation but thought he was, and tipping his grapefruit spoon to the camera, lied, ‘Oh, I’ll be back,’ before sliding out of the room playing the harmonica.

She asked me what I thought of the whole charade, whether or not to debase herself, whether or not she should spar for authorship, and a few other things I accidentally crunched Pringles over. I went straight to the voice of authority that comes to me after 2am saying something like ‘If you don’t do it, there’s plenty of those enthusiastic types that would, and for free,’ which wasn’t really an answer, but it was the best anyone could do in their pajamas. She looked unconvinced, so I told her by the time I’d woken the next morning, I’d have a solution. I don’t think she believed me, but I was a woman of my word and enjoyed making life really difficult for myself–it’s how I dated my ex so long. My answers for myself were pretty uncompromising, but I was too out of shape to advise others and just generally unseaworthy–I found simple life practicalities difficult to navigate, once getting myself trapped behind one of those little tray tables on the plane. But I wanted to be helpful. I flapped around trying to find the book I’d been reading, a quote I’d underlined in Natasha Stagg’s Surveys, maybe that’d be helpful, or not, but my apartment had become the Bermuda Triangle since I’d had a kid, and I couldn’t find it anywhere. I Googled it quickly and read it out to her like I’d memorized it verbatim:

“People who watch and do not want to be watched, people who listen and do not want to talk, people who live vicariously, are just perverts, and no one should want them around.”

She was listening but also flipping through the San Fran Chronicle, eventually saying, ‘‘What’s that supposed to mean.” I told her I didn’t know, and we moved on.

We bitched about life for a while, complaints about our finances, the art world, climate change, Jehovah’s witnesses, our careers, the false bottom in academia, all while eating reckless foods and scheming up our next book collaboration that would rewrite the history of 18th-century pirates through a feminist lens, and be undeniably brilliant. Her very distant aunt on her mother’s side, Anne Bonny, the daughter of an Irish servant girl, had been a pirate of the Caribbean during the 18th century–she was very proud of her mother’s side. Anne was illegitimate, so her father disguised her as a boy, ‘Andy,’ and put him to work as a lawyer’s clerk. Lawyers often become pirates, I’m told. It was all very cliché, the red hair and fiery temper, yadda yadda yadda.. and the story culminates, if my friend’s version is to be believed, at the Beetle’s hit pop-song ‘My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean,’ a delicious piece of pop-culture baklava, but whether or not I actually believe this changes from day-to-day. We swung wildly on ropes from buccaneer piracy to art writing piracy, where we’d remain for the rest of the night.

I had a distinct slackening of interest in the art world that’d made life pretty easy, I wasn’t stymied in its asthmatic shrubs and had an intractable position on the whole affair, but unfortunately, people don’t always want to know what you think, even when they ask you what you think. You’ve got to be able to tell the difference. She’d reject the contract if she had any integrity at all, but passing it on made her complicit in a whole other way. Keke was now back in the frame, eavesdropping like an underfed watchdog with the moral code of Nelson Mandela, and would’ve said his piece if my friend took on the article and fed the machine. Knowing this, she changed the subject abruptly; life was humiliating enough… ‘Everyone’s having kids, it’s disgusting, eleventh-hour kids, which is even worse…I hope to catch HPV, so I don’t have to get my tubes tied.’ The change of topic was obvious, even to a person wearing hibiscus flowers at 10am. I said something in thinly veiled code like, ‘Get HPV, don’t get HPV, it’s all the same in the end, but one of those is much easier to live with.’ She nodded like she’d understood, and Keke looked approving in the background, announcing his departure for his weekly dumpster dive, gleaning rotting fruit and the occasional rosehip oil from Health Food City. Our version of dumpster-diving wasn’t as romantic, but you have got to take what you can get.

‘You’re right, she said, ‘I’ll take the gig, and besides, there’s always San Fran Bridge.’

e x

—

Estelle Hoy is a writer and critic based in Berlin. Her second book, PISTI 80 RUE DE BELLEVILLE (After 8 Books, 2020) was just released, with an introduction by Chris Kraus. Her forthcoming, MIDSOMMER, cowritten with Sabrina Tarasoff, is scheduled for release from Mousse Publishing in 2022.