BILLY RUANE (1957 – 2010)

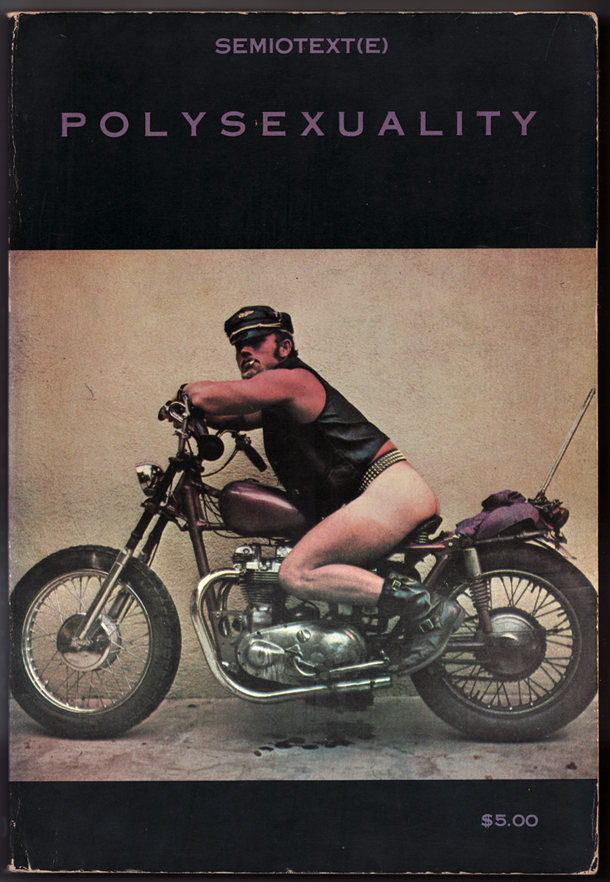

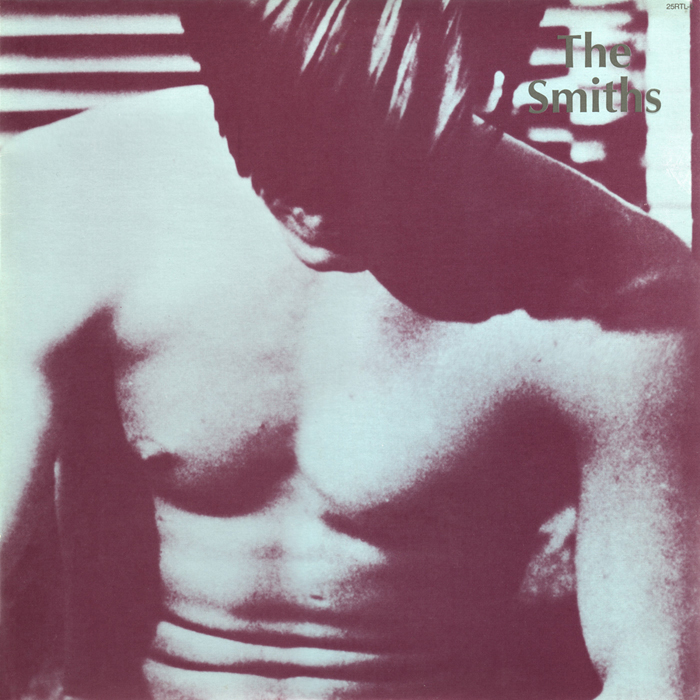

— Billy first appeared in my peripheral vision sometime in the mid eighties, looking like a junior law partner in the middle of a lost weekend: blazer, good shoes, trench coat if the weather required it, hair perpetually growing out of a respectable cut. I would see him at parties looking glazed, tie hanging loose or stuffed in his pocket, shirt unbuttoned to reveal a hairless chest, flushed from his spastic-balletic Cossack dancing. I got to know him a little when I was dating a motorcycle mechanic who he called on—weekly, it seemed—to patch up the scooter that got him around town. He would wheel his bashed-in Honda up to A—’s driveway after a late-night fender bender and then stay on talking to whoever was around. He could hold forth on a sweeping range of cultural topics… Hank Snow, covers of Hank Snow songs, snowshoeing, the snowy climes of Eastern Europe, until eventually he was extolling the healing properties of his favorite brand of Russian mineral water or critiquing Nabokov’s translation of Eugene Onegin. I got the idea that there was nothing about which he was not enthusiastic, or at least curious. His voice—stentorian, urgent, rushed—told me that his enthusiasm was shot through with mania.

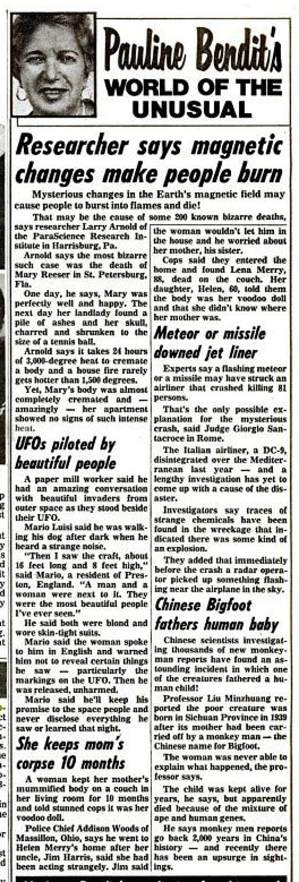

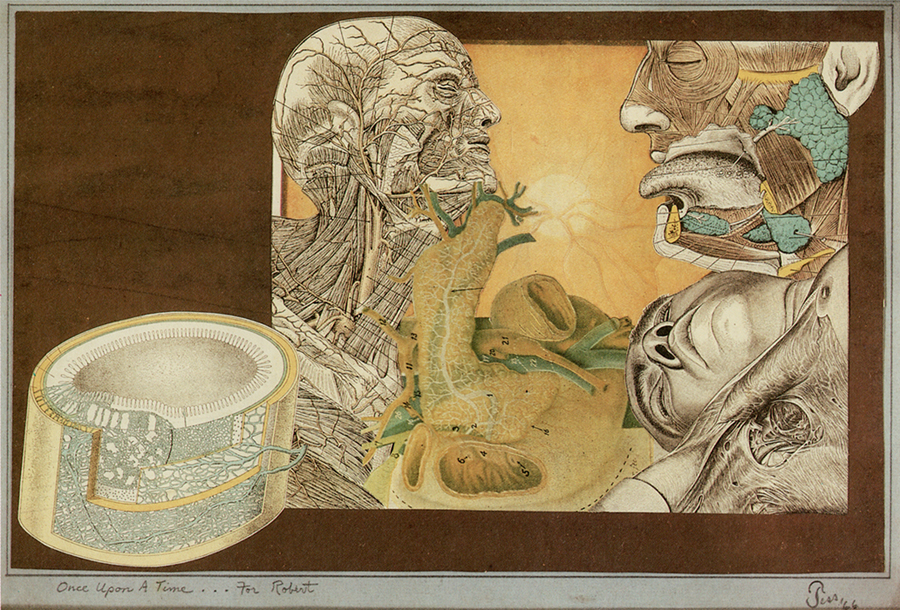

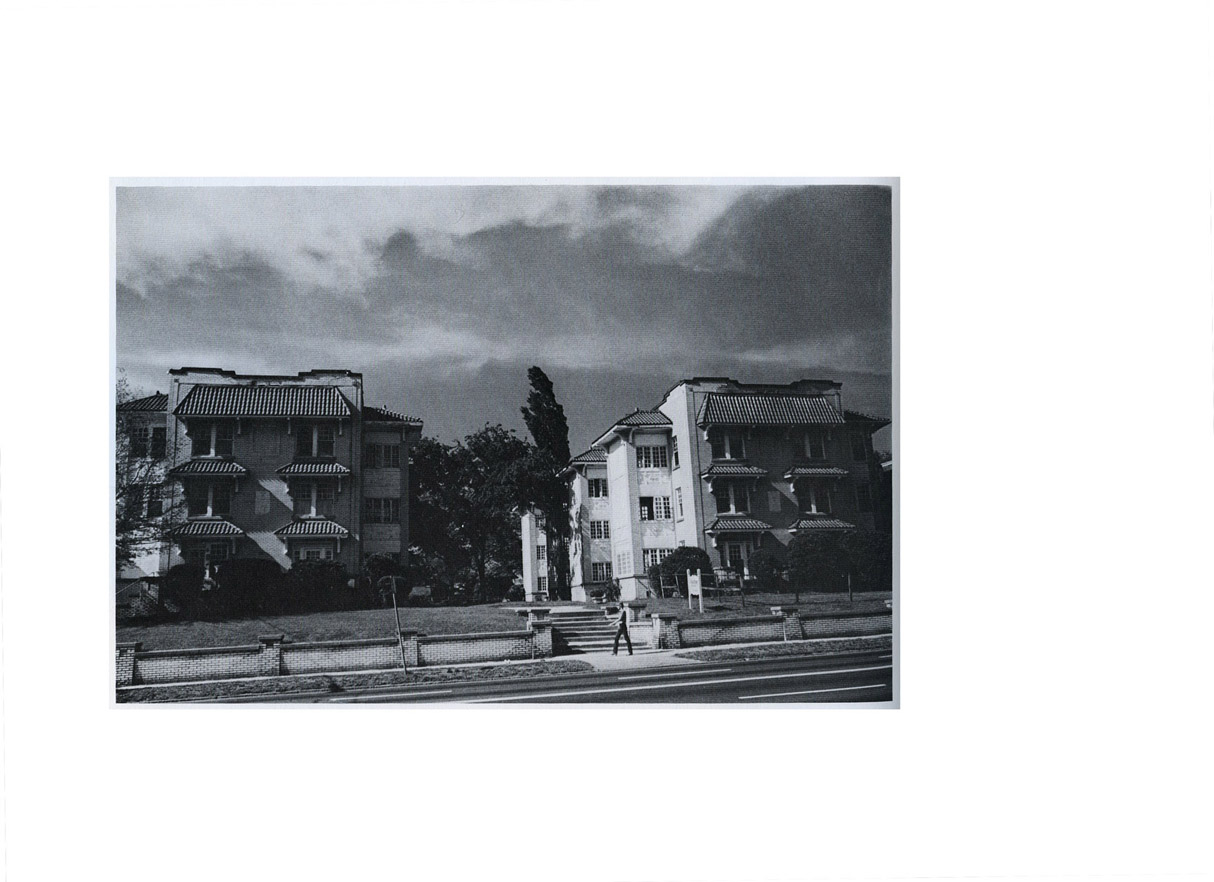

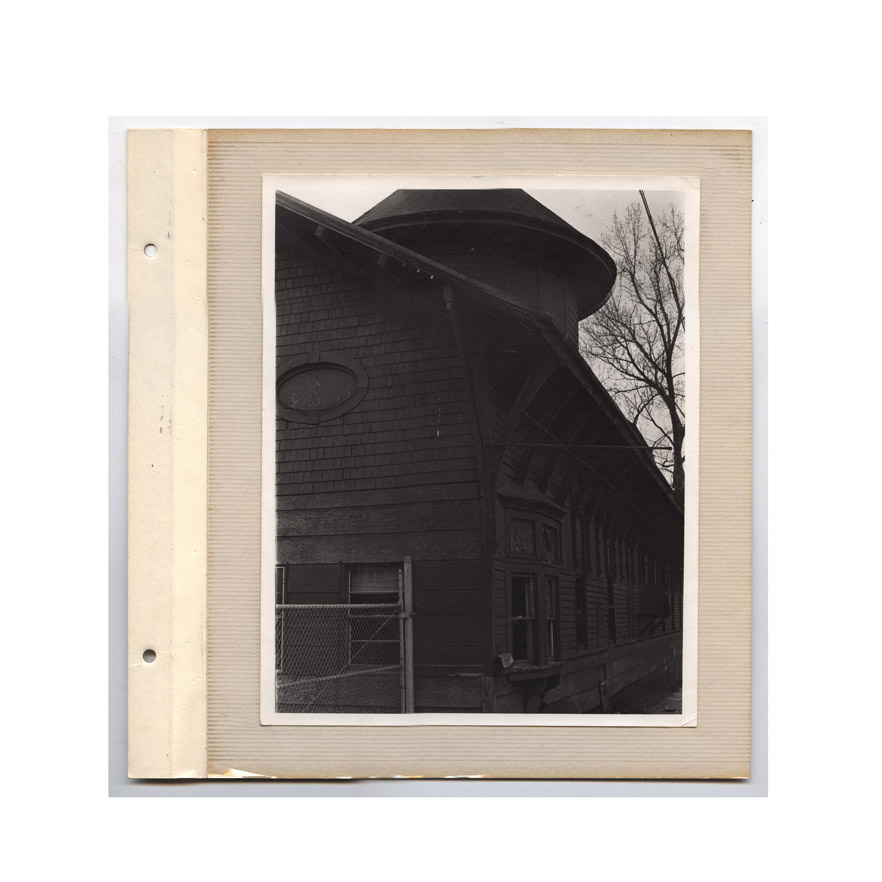

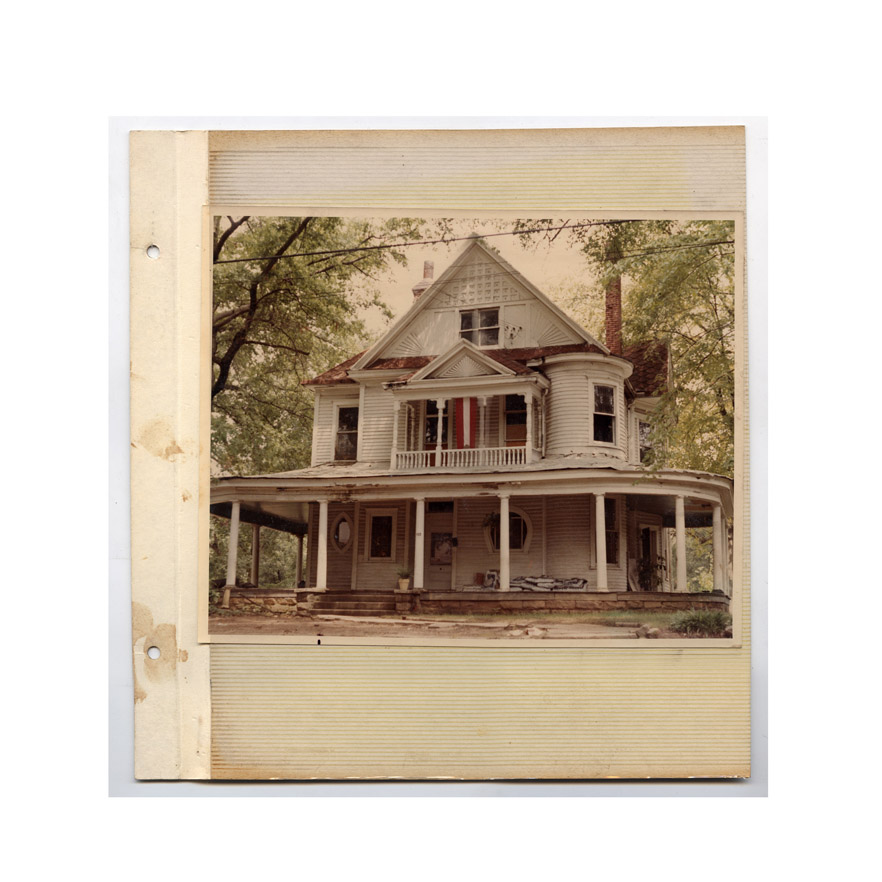

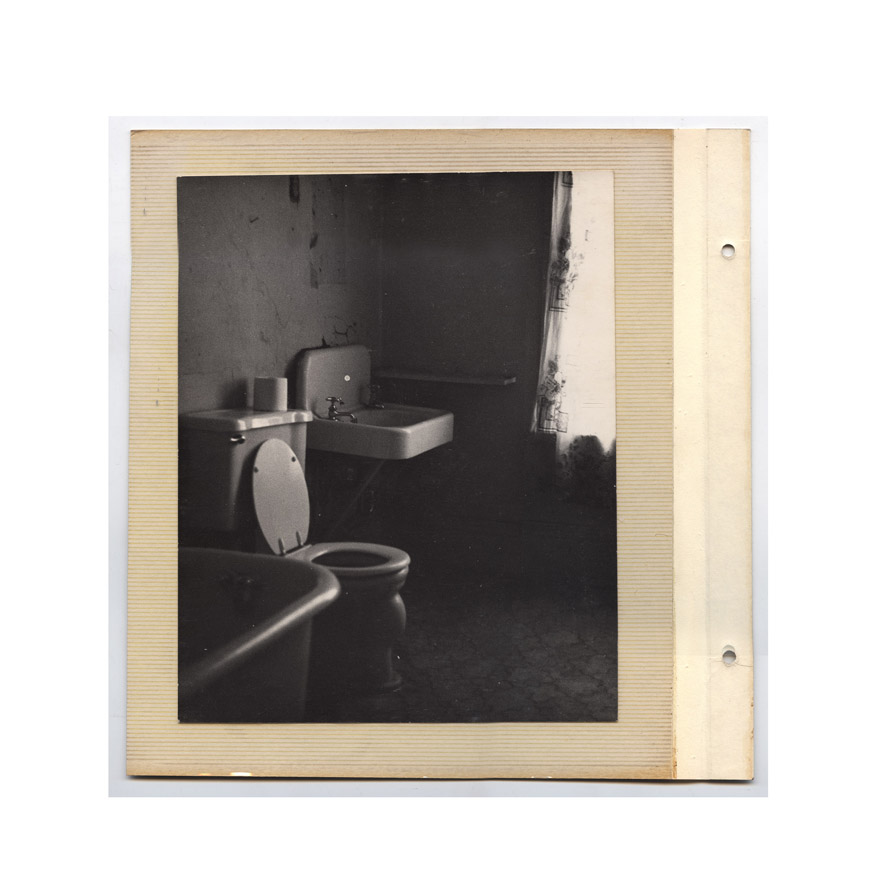

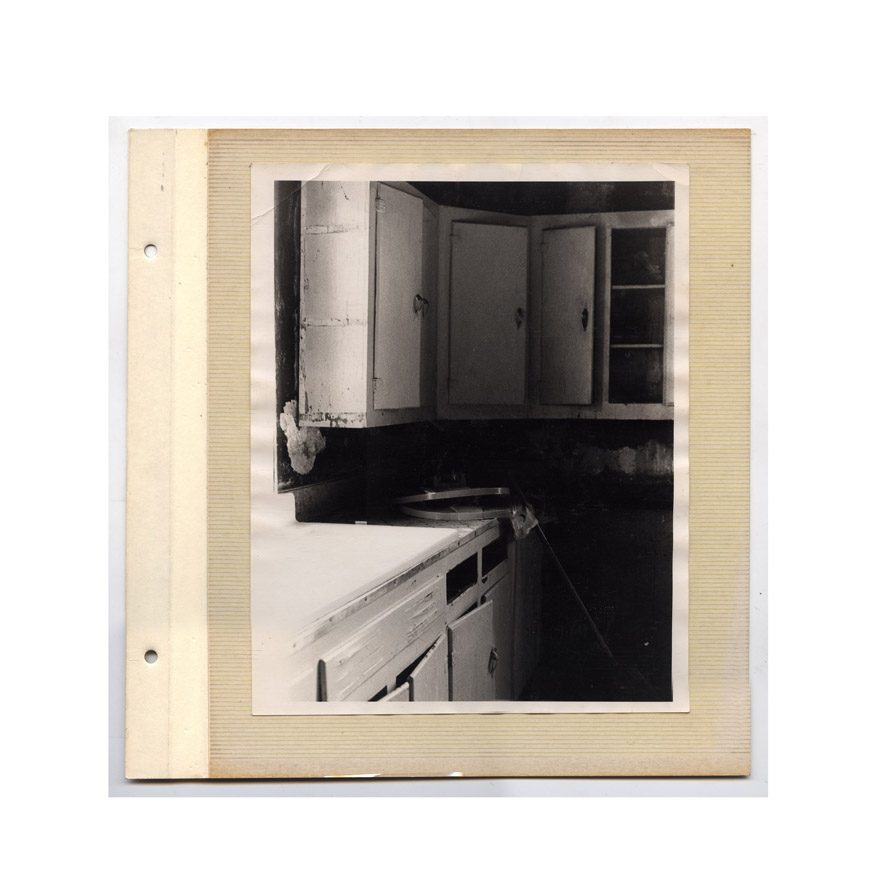

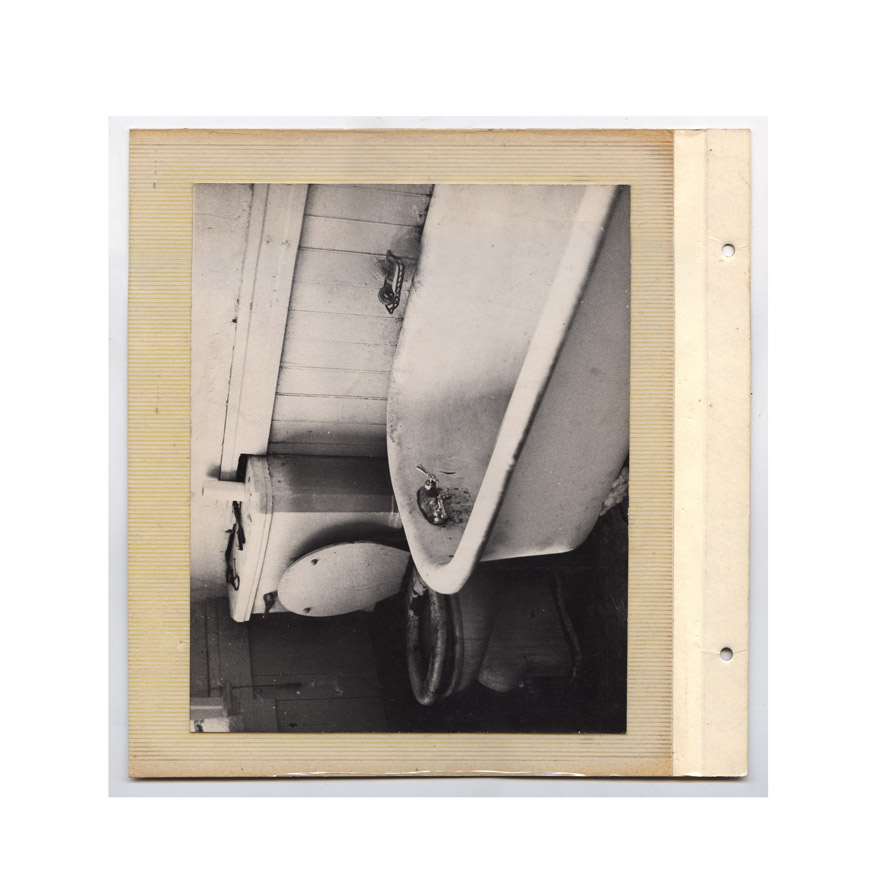

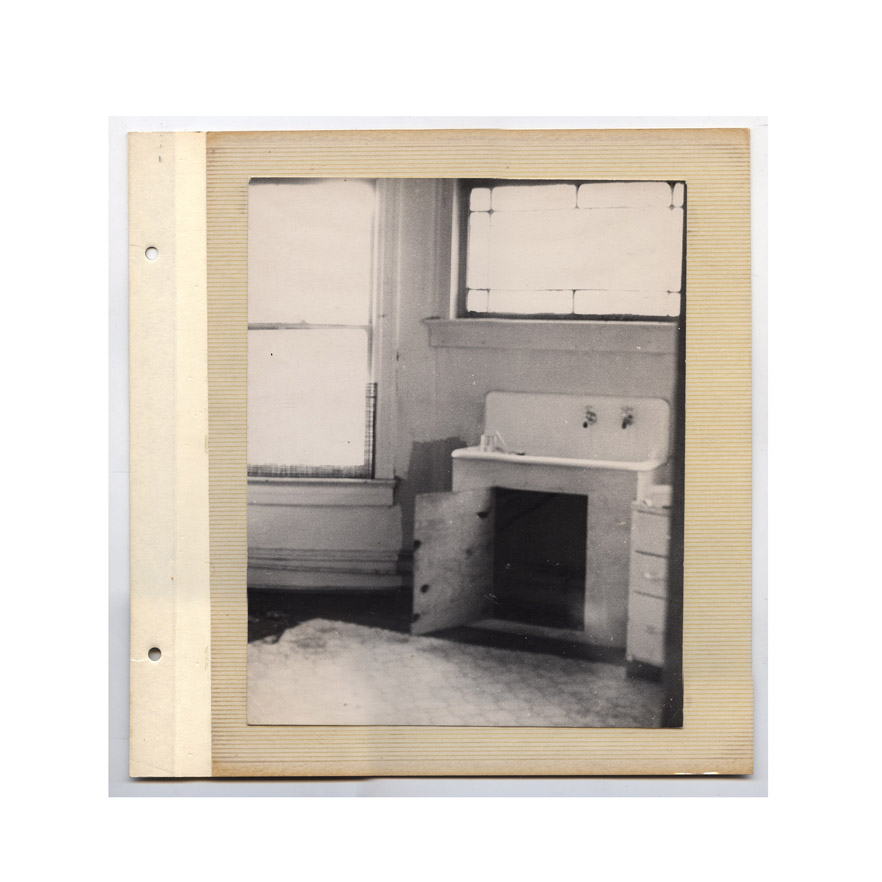

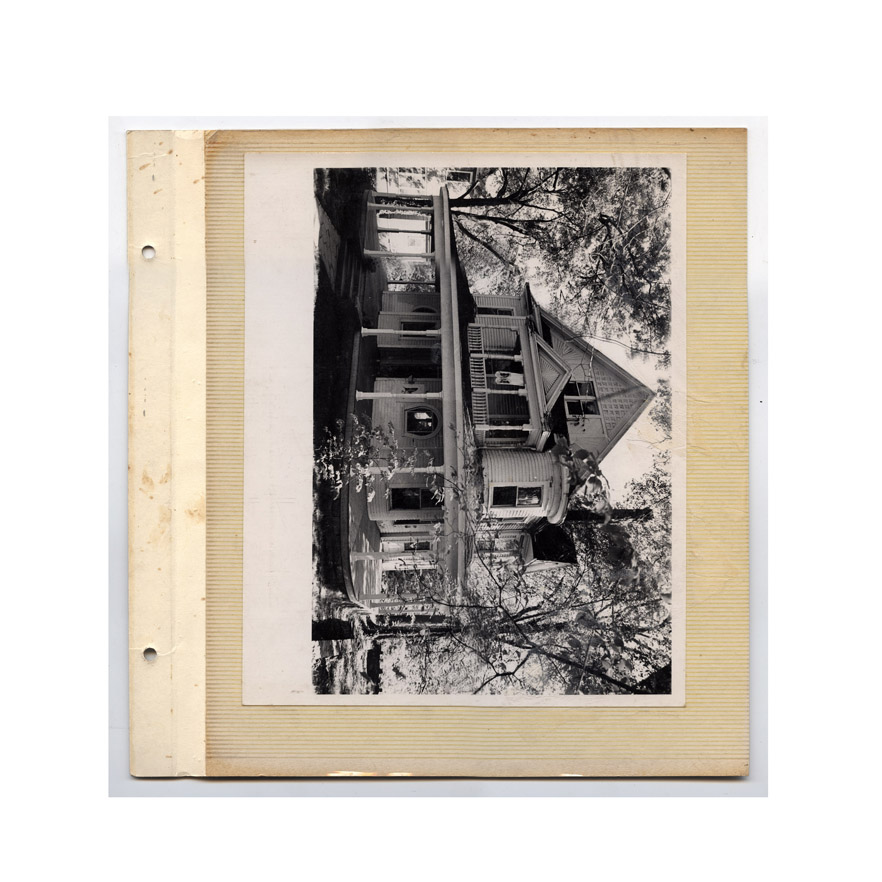

I know now that Billy was a fixture on the Boston rock scene long before I met him, but I wasn’t really traveling in those circles yet, so I began with a different set of associations. My siblings and I were then still operating a rooming house our father had left us when he died, a large Queen Anne Victorian in a quiet West Cambridge neighborhood, which he bought in 1968 and filled up with rent-paying eccentrics. Throughout my childhood, we shared bathroom and kitchen privileges with graduate students, émigrés, intellectuals and pseudo-intellectuals, psychics and skeptics, melancholics, alcoholics, and psychotics. Many of them were permanently unattached men, often brilliant, who lived apart from the traffic of majority opinion and followed no career path of any normal kind. Our dining room was a salon, most active in the small hours, where they aired their counter-intuitive opinions about diet and medicine, government, culture—high, low, and other. Without thinking about it much, I understood Billy as someone who, though he didn’t, might have lived in our house.

When I saw one of our tenants around town there would be a slight hiccup, a momentary adjustment of the domestic/public alignment. It was something I felt with Billy as well. And I began seeing him everywhere: downstairs at Cheapo Records, or in the next aisle at the Russian grocery store, or coming out of the Hong Kong with bags of reeking food, or—this happened often—I would be at the Brattle Theater watching, let’s say, The Reckless Moment, and I’d hear raucous and inappropriate laughter from the dark balcony, and it would be Billy.

Once, he called up and invited me to a movie. We sat in the balcony. He’d brought along a knapsack bulging with bottles of beer, and he offered me one as we sat down. Soon, empties were clanking around at our feet, and my right ear rang with his inappropriate, shouting laughter. (And people were hissing at us in the dark. Let’s say the movie was In a Lonely Place.) He suggested we go for a bite to eat after, and he asked over cheeseburger specials if I wanted to be his girlfriend. I demurred. It wasn’t awkward exactly, but it broke my heart a little the way he looked at me: fondly but with disappointment, like maybe he had overestimated me. There were no hard feelings, though.

By that time, Billy had begun his legendary run booking music several nights a week at the Middle East restaurant. We all knew, even at the time, that we were living through a fertile period of club music, and that Billy was making a lot of it happen. Under the auspices of Helldorado Productions, Billy’s programming was astonishingly eclectic and sometimes visionary. He lived frugally on an allowance from his wealthy father and quietly subsidized his Middle East shows, padding guarantees for bands who needed gas money, or who had equipment stolen on the road, or who just hadn’t drawn the crowd he felt they deserved. It’s a story often told, and I wouldn’t be the one to tell it anyway. I spent my share of time in the back room at the Middle East, though, where he presided: greeting and kissing and dancing shamanically, screaming encouragements, taking the stage between acts to spin marathon toasts and free-associate from stacks of index cards (and, sometimes, to carry on shouting matches with off-mic staff members).

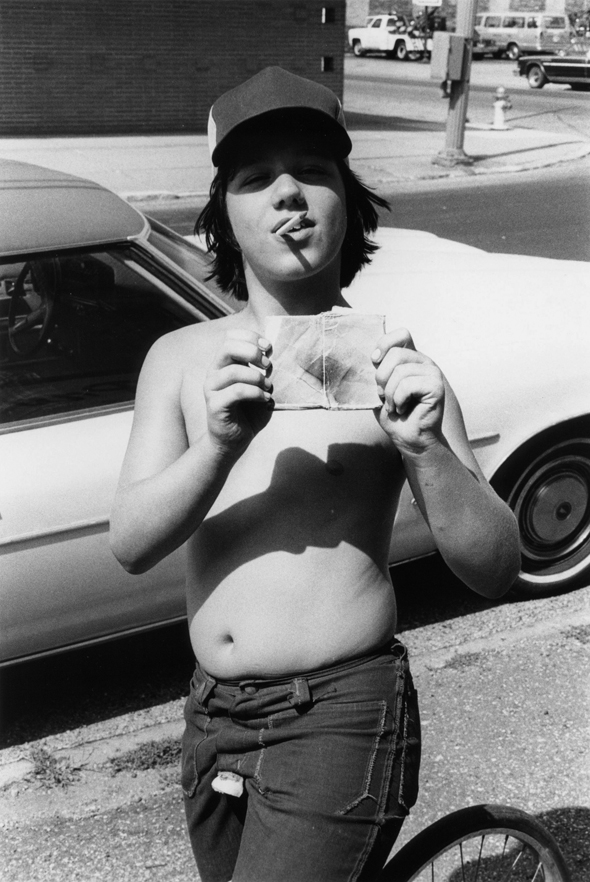

As for me, I was cocktail waitressing at Green Street Station in Jamaica Plain—a roadhouse on the gloomy fringe of the scene, popular with bikers and local drunks, or at least those who were sufficiently wet-brained or deaf to tolerate the all-ages metal shows. The air was heavy with the sadness of a thousand coke binges. Compared to the Middle East, it seemed like a terrible place to work, but it was all I could get. I wanted to tend bar, but the manager only hired his kickboxing buddies for that. I did a lot of languishing and fuming at Green Street. From my vantage point Billy’s Helldorado Productions cast an Apollonian glow. On my nights off I’d head over to Central Square, where I’d be greeted by Billy (if by no one else) like a visiting dignitary.

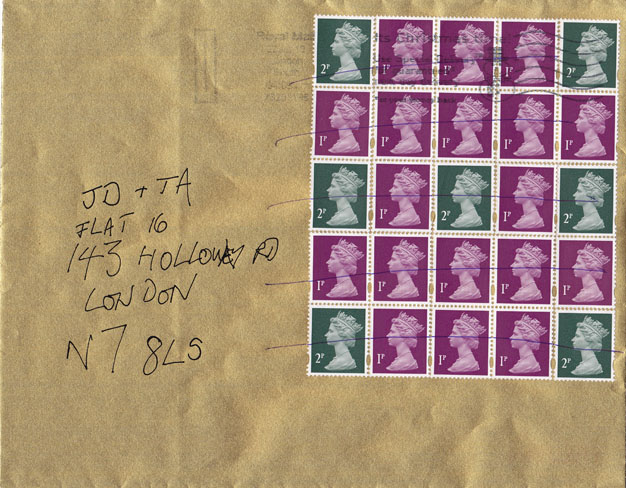

My solution, eventually, was to move out of town. We had long since gotten rid of the rooming house, and the tenants had scattered or been reabsorbed into the city. Many old friendships didn’t hold up, but Billy, in his way, was constant. I’d run into him on the street or in a bar, or I’d stop by his apartment and find him amid the teetering stacks of VHS tapes and Chinese take-out containers, and he would press into my hand one of his wonderful mixtapes, annotated in tiny Helldorado font: music for the drive home. India Adams, George Shearing, T.S.O.P., Terry Allen.

Once, I dropped in on Billy’s Monday night show at the Green Street Grill (the one in Central Square, not my old haunt, which had since become an Irish pub, then the world’s most sinister preschool, until finally it was knocked down to make room for condominiums.) Billy spotted me from the stage and worked me into his introduction: “A special surprise guest tonight, Ladies and Gentlemen, all the way from Philadelphia, Miss Mimi Lipson. Give her a hand, people.”

The thing to remember here is that I was one of hundreds, maybe thousands of people who got the royal treatment from Billy Ruane.

Fifteen years went by in snapshots. Sometimes Billy was doing well, sometimes not. There were occasional phone calls, a few inexplicably angry ones, but he was always glad to see me. Once, for no apparent reason, he wired me $300 Western Union. I called him and told him I wouldn’t accept the money. I was a little hurt, actually; it felt like the friendship equivalent of a $50 bill on the dresser. But I came to realize that, as he became less involved in booking music, his epic generosity took on other forms. When I saw him now, he always seemed to be buying rounds for his ever-expanding public. His father bought him a condominium, but he let friends stay there and kept to the teetering stacks and leaky roof of his old apartment. Eventually, I took him up on his repeated offer and stayed at the condo myself.

Billy was sitting at his computer in his apartment in Cambridge the night his heart gave out, probably weakened by decades of guzzling caffeine pills, prescription speed, and mega-doses of B vitamins. Within hours, the Internet was crowded with reactions to his death. A vigil was announced, and a wake, and plans were set in motion for a memorial. I was in another city, seeing the events unfold on my own computer screen. I googled, refreshed, clicked on links, looking for consolation. After a few days, though, I began to sense my own Billy Ruane vanishing in a snow globe of public commentary.

The last time I saw him was New Years Eve at the Plough and Stars. He was wearing a black overcoat and, as always, a plungingly unbuttoned shirt. His hair was brushed back from his bloated face in two white crests. I introduced him to my boyfriend and tried, unsuccessfully, to buy him a drink. Later, my boyfriend said Billy reminded him of an old Tammany Hall ward heeler. Actually, that’s not a bad analogy for the thing that Billy did. Look through the comment threads, the bouquets left on his Facebook ™ Wall ™. You’ll see there a tag cloud of corporeality: Billy Ruane conjured by kiss, laugh, dance, sweat and stubble.

This is what we’ve lost: a physical, door-to-door kind of scene-building that will never rule the day again in this age of so-called social media. I refer not just to his tireless distribution of Middle East fliers in six-point font, his mixtape cassettes and free drinks, but also the stubble, the sweat, the crazy spastic dancing, the hooting laugh, the persistent odor of fried won tons that collectively, urgently signified: Billy Ruane.

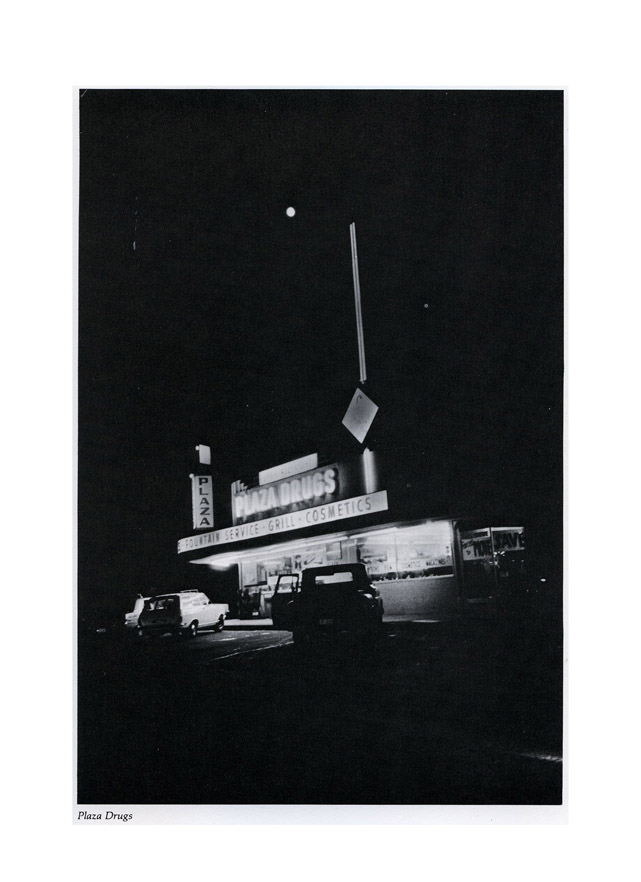

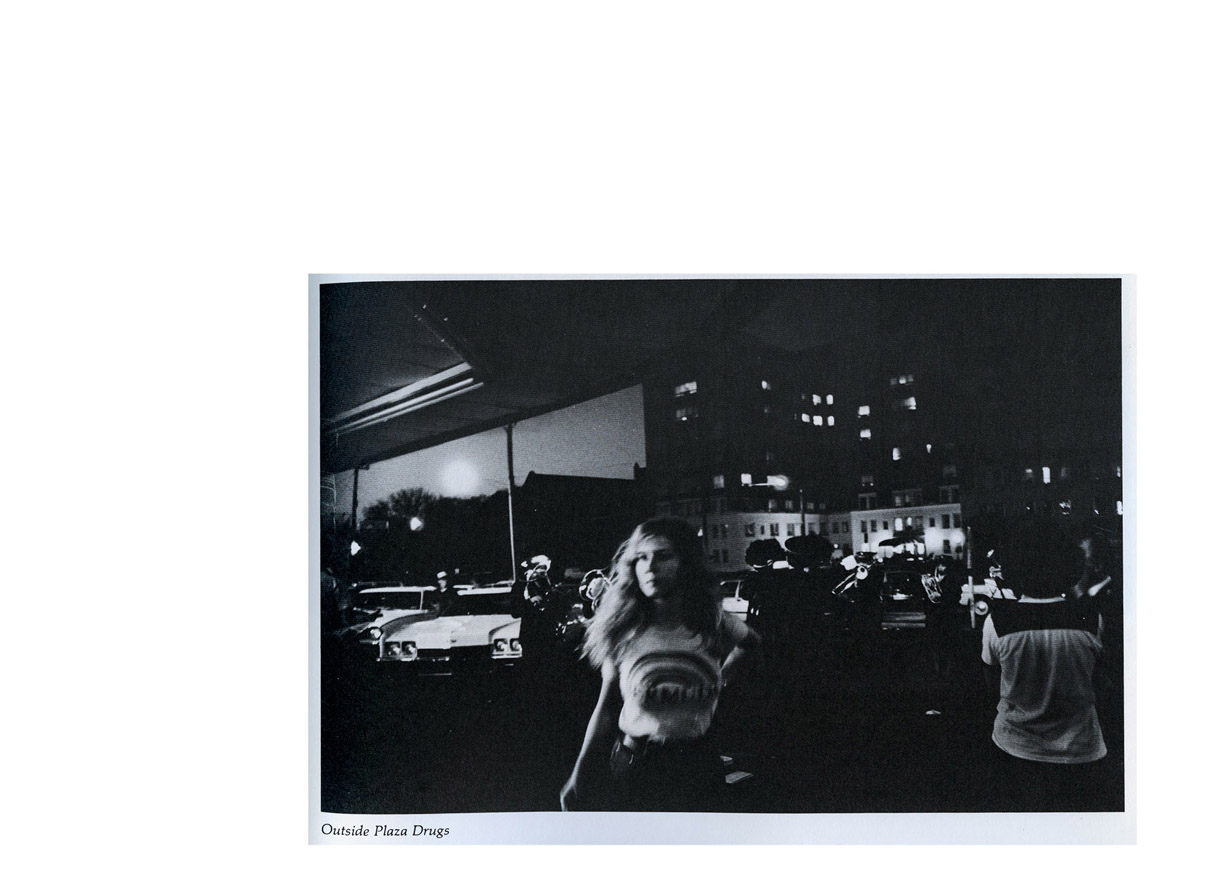

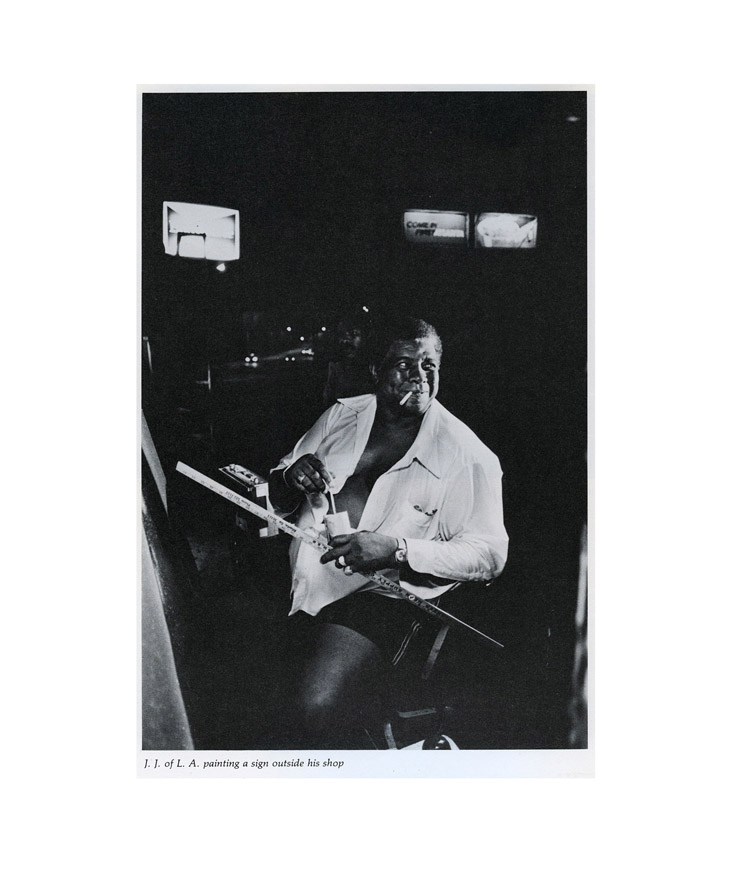

All images by Wayne Valdez.

—

Mimi Lipson was born in Ithaca, NY in 1965 and grew up in Cambridge, MA. She currently lives in Kingston, NY. She works at Bard College, writes, and makes rather unusual stained glass. Her chapbook FOOD & BEVERAGE is available from All-Seeing Eye Press.