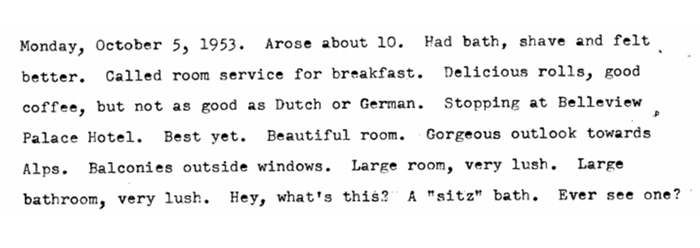

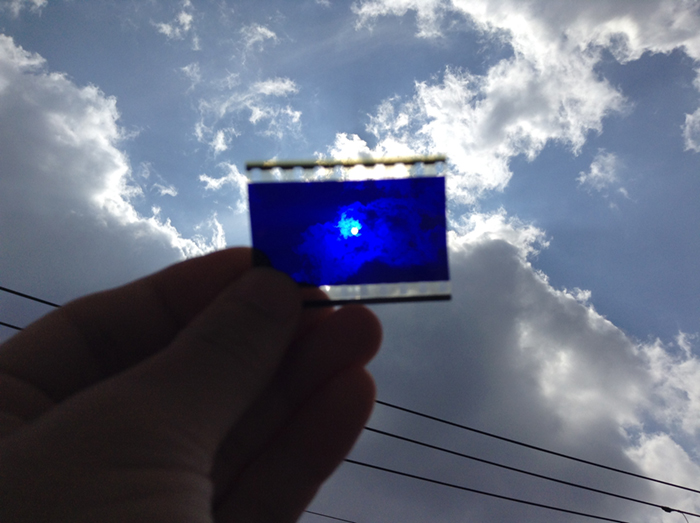

— My non-religious upbringing provided many gifts, but withheld one that would later become meaningful to me: the automatic right to one of these:

My parents, one born in Greece and one in the U.S., were married by a civil ceremony in the latter country that went unrecognized in the former, which did not separate church and state. My father would joke: In one of your countries, you and your brother are bastards.

*

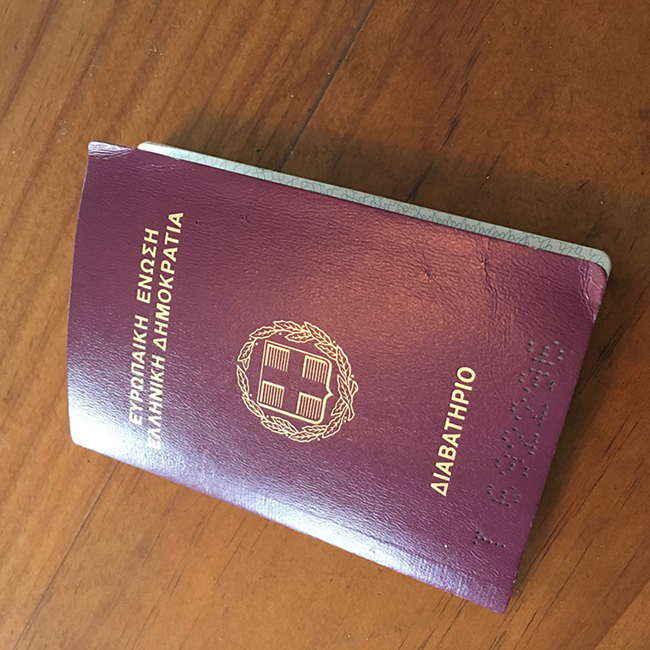

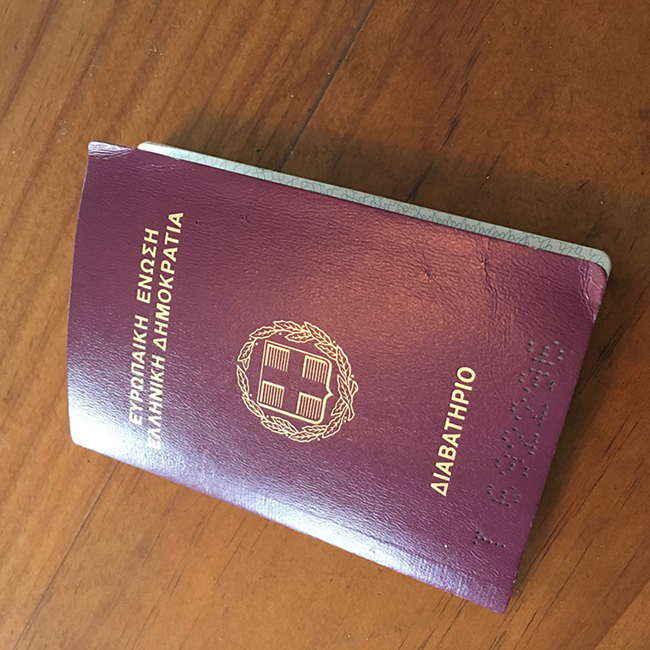

I keep my Greek passport—hard-won fifteen years ago, now expired—in a drawer along with an unofficial copy of my birth certificate; three U.S. passports (two outdated); and a duplicate New York State driver license I acquired last year when I thought I’d lost mine, but that I hold onto in preparation for whenever I lose the original for real.

When I open that drawer, as I did earlier this week, I pick up the inert thing and wonder: What is the value of an expired passport? What does it mean to be—to presume to be—unprecariously documented; to be doubly documented, to move between states of documentation? To be stamped legitimate in one nation, illegitimate in another? What is the trace of belonging or desire that marks the status of these outdated or surplus documents as less than valid or validating, but still somehow—until you need them—greater than zero?

In Greece, until recently and possibly to this date, the most official records of an individual’s right to be counted—the connection of each documented resident to a specific neighborhood—are written in ink and copiously rubber-stamped in tabloid-size ledger books that require two hands to turn a page. In cases where the records were burned in a fire, as I seem to remember some long-ago paperwork for my family was, there is no clear mode of recuperation. A hole replaces the certainty of any attestation. In a culture where linguistic and cultural fluency remain fundamental tickets to entry, some residents are much more vulnerable than others to falling down this hole.

*

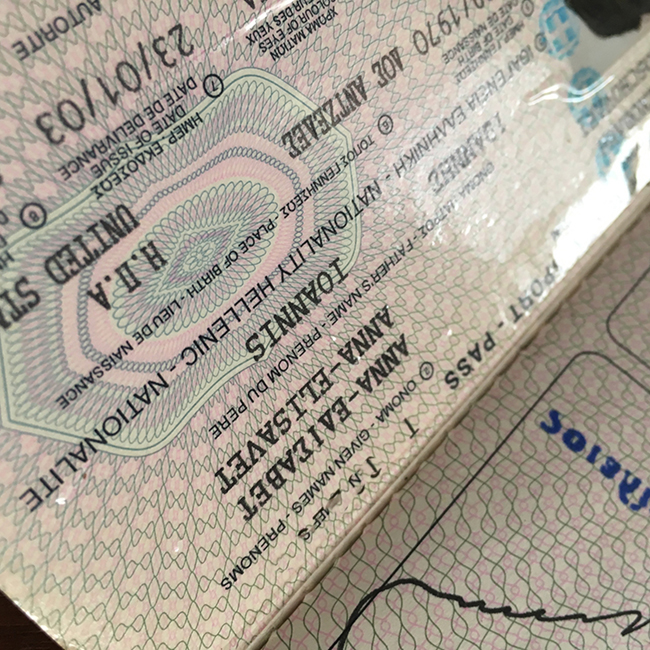

One day, my brother and I will inherit a small apartment in a port-side suburb on the outskirts of Athens. In fact, thanks to a tax-resistant culture and a tradition of transferring ownership from parent to child well before death, we already technically own it. For this to happen, we had to be claimed as our father’s legitimate children; this entailed my parents’ waiting years for civil marriage to be recognized in Greece, then filing for one; the further step of citizenship entailed additional bureaucratic actions, including my eventual appearance at the local precinct to have my name entered in the two-foot-high ledger book, smudged by a stamp.

Here is a photograph of the entrance to the apartment building, screen-captured today via Google Street View but clearly taken in summer. If you could make out the front door—one level below the lowest visible portion of balcony—to its right you would see a mailbox that during my teenage years functioned as a site of obsessive, expectant desire, the only way—years before email or social media—to be certain my friends and crushes back home hadn’t forgotten me, written me off to my other, still officially unacknowledged and insufficiently inhabited national self.

The apartment was new in the early 80s when my family acquired it, a belated replacement for the semi-rural house my father’s father had long owned in the older, more working-class sector of the same suburb, a house that suffered extensive damage in the 1981 earthquake. My parents exchanged it for a spot in one of the new buildings that were certified earthquake safe, a claim hard to trust when the narrow balcony of our 8th floor apartment seemed to sway in the slightest wind.

*

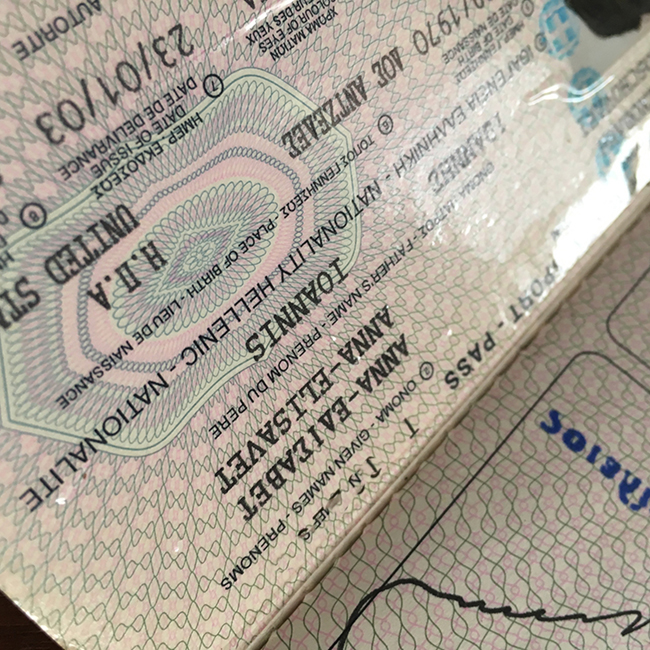

My first name in Greek, written in capital letters, is ANNA—the same as in English. In sentence case, it’s Avva. The duality collapses and expands on a habit, on a whim. Please print your name in block letters, one per space. Do not use all-caps when filling out this form.

*

The reason I let my Greek passport expire is that inside the country its power is more than duplicated by the national ID card I had to get first, which legitimates residency, intra-EU travel, and the right to work, and which remains valid forever. My dad reminds me: the only reason to renew the passport itself would be to use it to travel between non-E.U. countries under something other than the U.S. flag. Last fall, I made an appointment at the passport office of the Greek Consulate in New York to apply for a renewal.

My middle name is Elizabeth, as was my mother’s middle name before she married. In Greek it’s rendered most often as Ελιζαβετ, though alternate phonetic approximations exist. My mother’s first name is Joan, which is sometimes adapted as Ιωάννα and sometimes transliterated as Τζον οr Τζοαν. This variability—or some kind of private judgement—stumped the Greek translator of my U.S. birth certificate, or maybe just the person who entered the translation into the consulate’s computer, one of whom neglected to enter a name for any mother at all. On the screen, tilted my way by the consulate’s passport officer, my father was listed as my father; the space where my mother’s name would be entered was blank. We’ll do the best we can, the officer said kindly, after staying with the problem for an hour past closing time.

*

I have some early memories from the house we lost to the earthquake: I remember its dark interior; the single heating unit in the small and windowless center room; the bright garden, the coiled, foul-smelling incense my parents lit to ward off mosquitoes. I also remember stories about the house, though it’s taken years to connect them. That it was once truly rural, on an unpaved street; that it was my grandfather’s pride and joy but he was rarely able to live in it; that it had been occupied by Nazis during the war and by the British in the years after; that when it was returned to my grandfather he didn’t move in but would take his lunch there, in his garden, on break from work in the next harbor town over. That he died in that garden, with no warning, two or three years before I was born. That when I was two or three years old, during the longest period we spent there, my mother suffered a double, debilitating grief and vanished into an uncharacteristic depression that left me temporarily bereft, a blank space in my life where her name would have appeared.

*

I am in Germany now, late February 2019, close to the site of its expired wall, my U.S. passport in my bag. I just learned that a U.S. citizen can be turned away from an international flight if their passport will expire within three months, no matter what their return ticket says. I think differently about the inheritance of property when I’m feeling sentimental about my family than when I’m not. I’m only learning now about my mother’s real relationship to religion, more nuanced than the strict atheist message I recall. I’m still hoping the Greek consulate will fill the hole in my documents and renew me; I’m still trying to learn passable Greek.

*

I Whats-App’d my father to ask for more details about the old house and its history. We talked for an hour, me mostly listening, letting the fragments connect. After, I messaged him for the address, which he sent, adding: Google Earth has an excellent view of it which shows the alterations the new owner made (closing the veranda and making a parking space) as well as the newly paved street.

From this view, I did not recognize the house itself. I did sense something familiar in the lot across the street, though there’s no telling how long it’s been empty, or if it hasn’t yet been built.

Then I thought to send the photo to my mother. It was full of white and yellow daisies, she remembered immediately. She would pick them—there was no fence—and bring them in the house.

—

Anna Moschovakis is a poet, translator, and author most recently of the novel ELEANOR, OR, THE REJECTION OF THE PROGRESS OF LOVE.

www.badutopian.com