WAYNE KOESTENBAUM

Tuesday, July 2nd, 2019FEVER CHART LANDSCAPE

Killing time before attending a panel discussion, I photographed these blue marbles in a toy store, East Village. Blue symbolized my nervousness about attending the panel, which I ended up loving. I sat in the front row, on a backless chair. I stared at the panel’s central participant, a handsome man who had been wearing blue overalls when I’d first met him, years ago. I always think of him as the man in blue overalls, though this epithet fails to encompass his fatherless charms. My hobby: losing my marbles, and then writing about the experience of loss.

I found, in the trash, a book with a corrugated cardboard cover. I tore off the cover and painted it thickly and sloppily with cheap blue matte acrylic. When the paint was nearly dry, I pressed watercolor paper against the corrugations, which left a raked imprint. A series of other, minor interventions on the paper occurred—gestures executed with a sensation of muted joy. The many marks constitute a stumbling language, nonverbal, as if in the lacustrine space where a knock becomes a throb, a fish becomes a portent, a red glyph (in baby guise) becomes a fever-chart’s oscillating, alarmist line. The line belongs to a landscape now, a vista I could call suckled by a borderline, an ambiguous phrase which suggests an origin-myth whose gory details I don’t have the strength this morning to unveil.

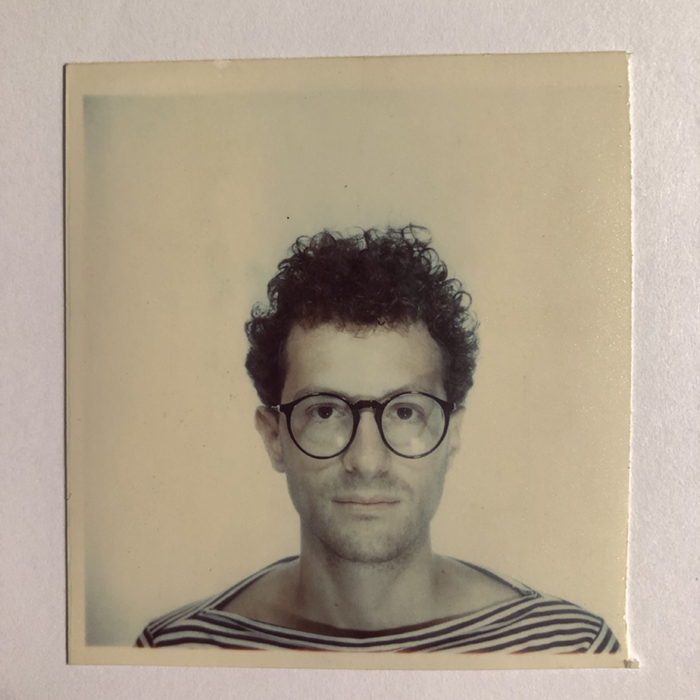

I denominate myself the figure in a horizontally striped shirt but in fact I rarely wear horizontal stripes. On a forgotten day in the early 1980s I wore a Breton mariner shirt with a neckline gaping open for my sliver-head (a merman’s) to slide through. The black horn-rims I wore, that day, that year, were too large, their oval apertures a technique of losing an unnamed sweepstakes. Who took the picture? Who asked me not to smile? Deracinated, pale, confrontational, I seemed to beg the so-called universe to uncover its unctuous alibi, to disclose the actual biography hidden beneath the fake front, a falseness I still embrace (or hold up for target practice) as a blamed nectar. Am I confusing or concrete? A devotee of the unnatural, I’m trying to speak now as plainly as possible.

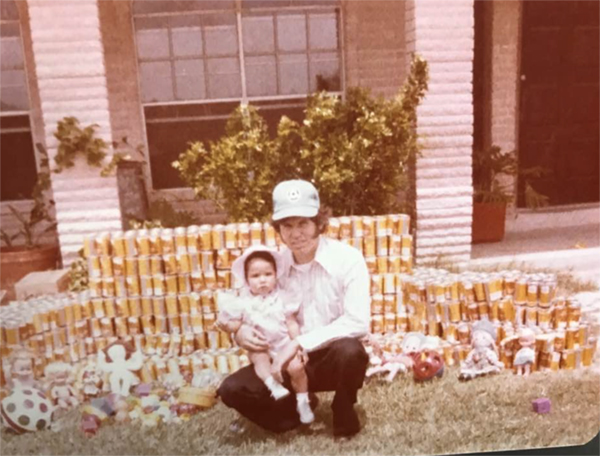

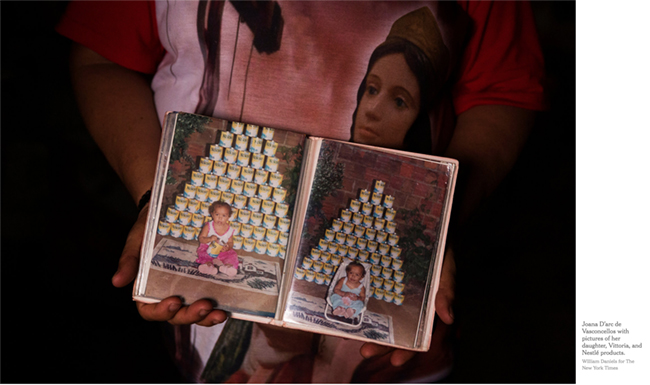

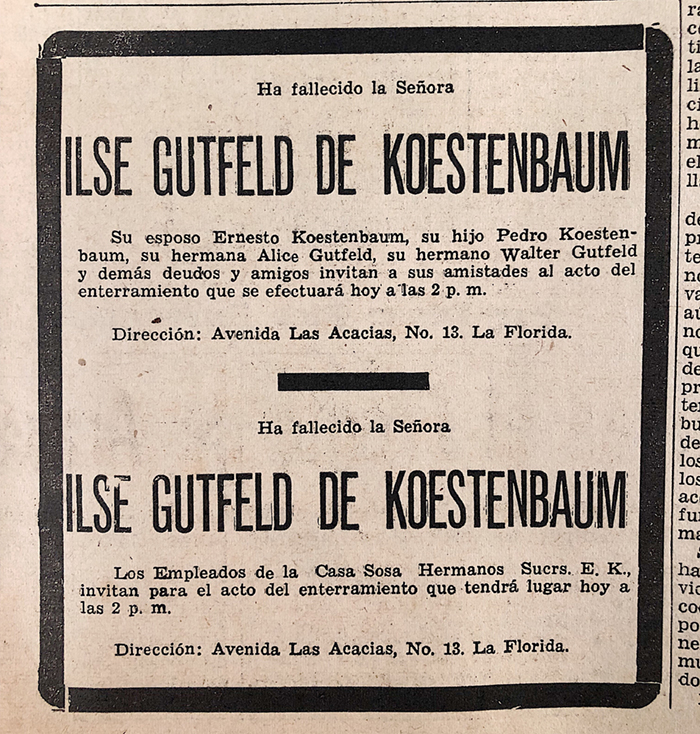

My father’s mother died in 1943. Enigma, she oversees my entire life. Her non-existence offers a comforting container: I can be securely held by her absence, a flawless design. Her death notice appeared in a Caracas newspaper: invitation to the internment, taking place on the Avenida Las Acacias. I’ve never been to Caracas; I can’t picture an acacia. A tropical tree? The loveliness of an acacia tree is beyond dispute. If I could decode the acacia’s symbolism, I might forge a route, non-poisonous, through the future desolation that awaits us. Notice how quickly I flee from funeral particulars into abstraction. My grandmother’s name, Ilse Gutfeld de Koestenbaum, contains a suspect preposition: de. Was it meant to confer a momentary aristocracy? Or was it simply the custom of the time, to insert a “de” between the maiden and the married names? My father once told me that his mother’s ancestors had lived in Germany since the 1500s, a fact, or supposition, that gives me an unjustifiable sensation of security, as if my family were a pharmacy that had been in business for centuries, dispensing floral waters and healing powders.

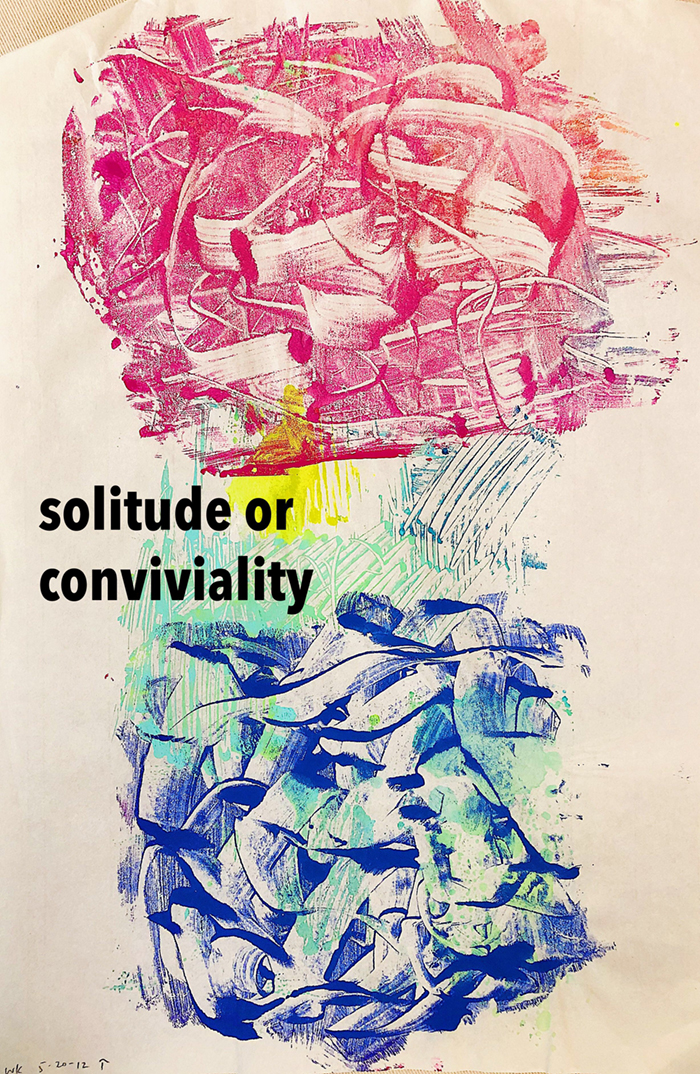

To drag a palette knife, a broad utensil, across a paint-smeared sheet, and then print the shadow of these unchoreographed, spontaneous oscillations on rice paper, not even needing a brayer to enforce the print-marks upon the all-too-willing page—is this capitulation to painted impressions a plea? A plea for what? The words solitude or conviviality arrived on the scene of the monoprint through the sleazy yet magical gateway of Photoshop, a name sacrilegious to mention within the precincts of this mess hall, where you can opt for porn or Bambi, crowd consciousness or forty days in the desert. I made this casual monoprint in 2012. Seven years later, I found it in an ignored pile of drawings. I’m the miscreant who ignored them. Toward my own leavings, I sometimes play the role of villain. On good days, overstatement elevates me to the status of salvager.

—

Wayne Koestenbaum is a poet, critic, artist, performer. He has published nineteen books, including NOTES ON GLAZE, THE PINK TRANCE NOTEBOOKS, MY 1980S & OTHER ESSAYS, HOTEL THEORY, BEST-SELLING JEWISH PORN FILMS, ANDY WARHOL, HUMILIATION, JACKIE UNDER MY SKIN, and THE QUEEN’S THROAT (a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist). His newest book of poetry, CAMP MARMALADE, was published in 2018. He has exhibited his paintings in solo shows at White Columns (New York), 356 Mission (L.A.), and the University of Kentucky Art Museum. His first piano/vocal record, LOUNGE ACT, was released by Ugly Duckling Presse Records in 2017; he has given musical performances at The Kitchen, REDCAT, Centre Pompidou, The Walker Art Center, The Artist’s Institute, and the Renaissance Society. He is a Distinguished Professor of English, Comparative Literature, and French at the CUNY Graduate Center in New York City.