YTO BARRADA

Tuesday, September 9th, 2014MIGRATION

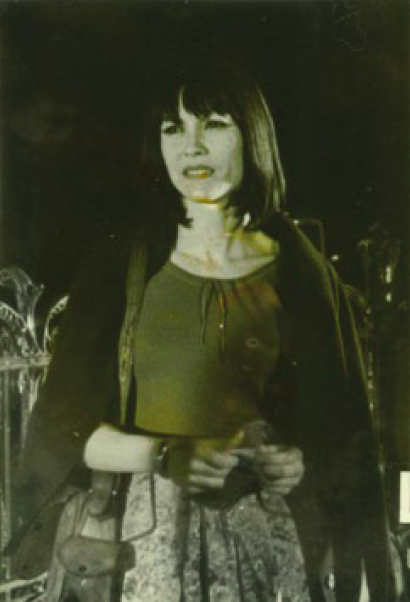

— Some years ago, anticipating my mother’s fiftieth birthday, I decided to track down a film she had been in, and which she had never seen. She remembered one detail: she had worn her own clothes, a long skirt with flowers.

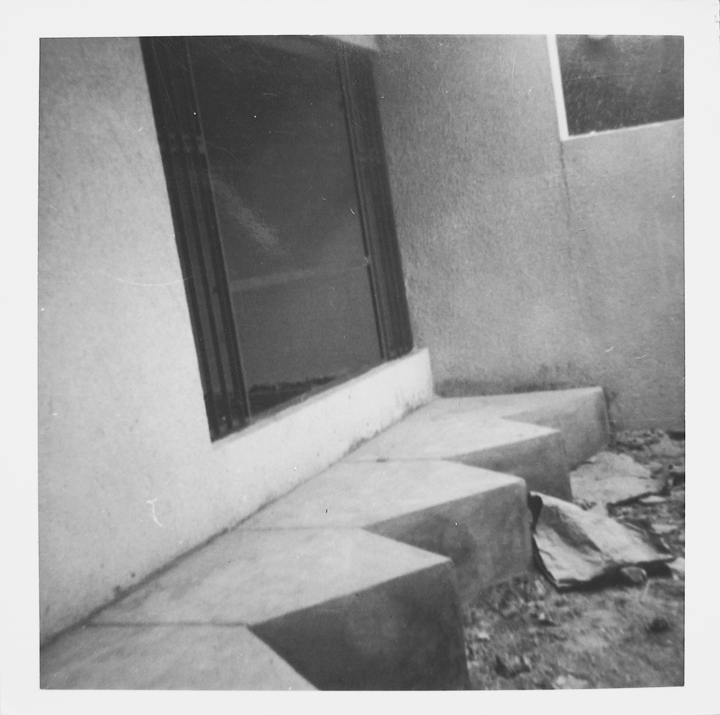

We had always kept a few black and white stills from the shoot, on which was inscribed, in white capitals letters “MIGRATION, A FILM BY AHMED RACHEDI.” My mother said she was the lead actress.

No other physical evidence — but a few clues from memory:

My mother spent her entire salary from the film on a trip to Lisbon, with some Situationists, to be present for the Carnation Revolution. So the film was shot in 1974.

Her scenes were shot in Paris, one around an elevated Metro station, and the other in a police station. (In the film as she recalled it, an Algerian immigrant arrives in Paris, meets a young Moroccan women—her role—on the Metro, and they get into a fight with a racist gang. While they were filming the fight, my mother left real scratches on the faces of the racists.)

The film must have been completed and released, since Scherazade (a sister of her sister-in-law) had recognized my mother one night while watching Algerian TV.

1994. The 50th birthday is coming fast. I find the director in the Paris telephone directory, and go to his office on the Champs-Élysées. He doesn’t remember my mother. Not very expansive, he informs me that he has no copies of the film, not even a VHS tape. The only way to see it would be for the film lab to strike a new new 35mm print. He hands me his business card, assuring me that will suffice as authorization for the lab.

At the lab, bad news: a print would cost thousands of francs, the equivalent of several month’s rent. All I wanted was a VHS tape. What would I do with a film print anyway? I had to abandon the project, and the surprise gift for my mom.

A few years ago. I am looking around IMDB and MIGRATION is not in Rachedi’s filmography. In 1974, nothing. In 1973, A FINGER IN THE GEARS, a political documentary on migrant workers; in 1978, ALI IN WONDERLAND. Was it a TV movie? An oversight? Maybe the title had been changed?

Or was the entire story one of the “family myths” I had learned to appreciate and take with a grain of salt. If so, my mother is probably in the film for 10 seconds — although she remembers spending days, weeks working on. My dad, an equally unreliable narrator in family memories, says it was a rape scene in the subway. What to believe?

Today, I am finally in a position to get to the bottom of it: I’m the founding director of the Tangier Cinematheque, North Africa’s first cinema cultural center, and one day soon, I’ll convince my colleagues to put on a retrospective of the films of Ahmed Rachedi. On my mother’s birthday.

—

Yto Barrada was born in Paris in 1971 and grew up in Tangier, Morocco. Her work engages with the peculiar situation of her hometown Tangier. Exhibitions of her work have been shown at the Tate Modern (London); the Renaissance Society (Chicago); Witte de With (Rotterdam); Haus der Kunst (Munich); MoMA (New York); the Centre Pompidou (Paris); the 2007 and 2011 Venice Biennale; Whitechapel Gallery (London), and the New Museum (New York). Barrada is the founding director of Cinémathèque de Tanger. In 2011 she was the Deutsche Bank Artist of the Year, and is presently a recipient of the 2013-2014 Harvard University Robert Gardner Fellowship in Photography. Her first comprehensive monograph was published by JRP Ringier in 2013.