LETTER TO HÉLÈNE CIXOUS

“I want to see what is secret. What is hidden amongst the visible. I

want to see the skin of the light.”

— Hélène Cixous from “Writing Blind: Conversation with the Donkey”, in Stigmata

Dear Hélène,…I begin by conveying to you the shock of what I have witnessed. These words are a translation of the visual experiences I had last night and early this morning. My words will be absolute, nothing left to interpretation. From my lash to your lobe. Trust me. Forget the perfidy for which I have become so renowned.

Tran T. Kim-Trang, a Vietnamese-American artist who lives in Los Angeles, dares to call her video work Aletheia, the philosophical concept of truth and possibility. To me the word is a proper name, an ethereal girl I might have known, Aletheia. I begin a precise tracing of the Aletheia image path that Tran lays before me. Go blind now, with me, Hélène. I will not let you loose in the darkness.

“Night becomes a verb. I night.”

— Hélène Cixous

We hear screeches. Mechanical hysterics. Braille surfaces flip and flop across the screen, overlapping, flowing by … completely unreadable without fingers of course. I wonder what this surface feels like to touch. Tran tells us that Trinh T. Minh-ha writes about reaching out through blindness. I think she finds the same freedom in the darkness that you discuss with the donkey. Hélène, vision is there within you but you too refuse the ease in life that it offers.

I am watching a woman’s mask being pulled off. Can you hear the woman’s voice? She’s accusing them (the people who claim to make history) of not being able to see into her “little squinting eyes.” They don’t reveal a thing!! Asian eyes are extremely good at closing out, keeping secrets, says the voice. So why do the little girls start slicing their own eyes? To my mind the slits are power! They open and close when they damn well please. Like the vagina, don’t you think, unless it is raped. Tran continues. She thinks about having her lids DONE. Her camera is slowly, slowly pulling out to reveal a cosmetic surgeon holding the face with the mask. I’m watching hundreds of Asian faces, listening to punk rock music screaming “I can’t see what it’s all about! Lights out, lights out!!!!”

“Let us close our eyes. Where do we go? Into the other world. Just next door… In a dash, we are there. An eyelid a membrane, separates two kingdoms.”

— Hélène Cixous

I listen to addresses of plastic surgeons in Beverly Hills, revealing locales on Sunset Blvd. I am eavesdropping.

I see a sign that reads “the Jew as blind.”

Then a parable of a child and the story of Cambodian women who have witnessed war horrors about becoming blind, then suicidal.

Aletheia is Tran’s farrago of blindness metaphors, her textual defense of an obsession with the receptacle of sight. She plays brazenly with the allusions, spinning them around like riddles we must decipher in order for a laugh and then…. a poignant sigh of tragic recognition. Tran is angered by the constraints put on the slanted eye in the modern kingdom, the West. As I watch this modern kingdom, I find nothing appealing about it, at least her view of the wealthy kingdom donned Los Angeles. I’d much rather close my eyes.

Next. There are more listings of addresses in LA. We’ve tumbled into the hell of Hollywood! Richard Pryor, blind groping men at peep holes … Sidney Poitier with a blind white girl,…blonde woman in vulgar, pornographic Hollywood movies about sex and blindness. A lascivious doctor talks about a cure for blindness. I am nauseated and wish I could close my eyes, Hélène. I never mentioned how much of life I would prefer not to see.

Return to mapping of LA, then ranting, ritual, obsessions with fashion, animals, a Native American parable in which a white man borrows an eye from an animal but it does not fit. “A candy colored clown they call the sandman tiptoes to my room every night” croons Roy Orbison. Oh, how I long for the dirt in my eye, the unconscious filtering of grit before it enters my consciousness. A clean, soporific blindness.

“…but I say that he who looks into my eyes for anything but a

perpetual question will have to lose his sight.”

— Frantz Fanon, from Black Skin, White Mask

Tran ends with Frantz Fanon’s rigorous, righteous eyes demanding only a perpetual question. Do you think that Tran would agree that eyes with this brilliant, curious questioning are windows into that rare thing — a lucid mind?

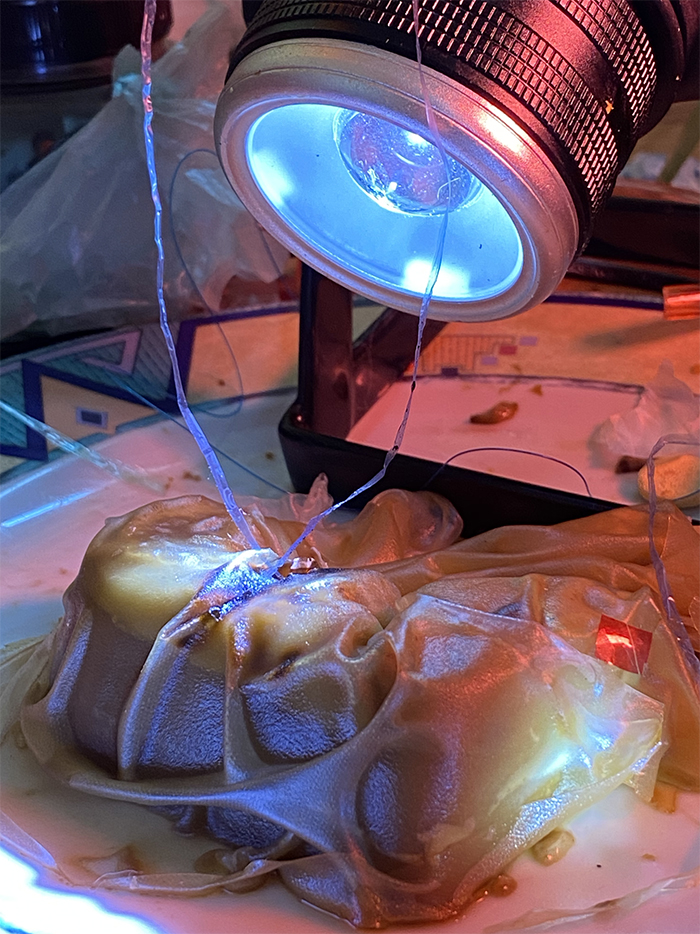

Tran’s next film is called Operculum An operculum is the plug of mucus that fills the opening of a woman’s cervix. It is also the bony flap covering the gills of a fish. An operculum also has something mysterious to do with fungi. Here flora and fauna are merging in a bewildering visual confluence. Tran is also thinking about cosmetic surgery to reshape her eyes, another approach to the sculpture of the face. She is doing research with her black and white video camera by visiting cosmetic surgery doctors who specialize in blepharoplasty (eyelid crease surgery) and learning that “the Vietnamese have a better crease.” I read text scrolling on the side of the screen about hallucinations after a lobotomy, while we are hearing seemingly objective descriptions of eye surgery for Asian people. I believe that Tran is telling us that both operations are a form of shock therapy. They both use a prick.

It is 4 AM. I am watching Tran’s Kore (sexuality, sex, fantasy, AIDS). Feeling promiscuous, but unaroused. “The eye, like the camera, seeks out its owner’s reflection.” The phallic gaze, horror movies, loads of ugliness, club dance music – all bombard my psyche. Kore suggests that the clitoris is another eye that can be shut: lesbian love making then takes on an all-powerful presence on the screen. A female AIDS health expert talks about blindness and drug treatment, like a perverse Public Service Announcement. She tell us to choose between death or blindness, that there is a problem with so many women being infected by men. We watch a penis image, graphic and grotesque. Kore seems to find an assertive comfort with the abject: “No erotic act has any intrinsic meaning.”

Again, I watch lesbian lovemaking with technomusic, one of the women is blindfolded. Do her eyes inhibit desire?

“the eye-penis”

“the phallic gaze”

— Luce Irigaray from Speculum of the Other Woman

I am reminded of that revolution I experienced in my mind and in my body the moment I laid eyes on Irigaray’s Speculum of the Other Woman. It was as though she were bringing a hidden awareness I had always treasured to my epidermal layer, finally visualized and sublimely conscious. With Tran, the meeting with Irigeray is not only beautiful but also violent, at least on the level of the imagination. Like a confrontation. For me, you Hélène Cixous and Luce were and are dear, dear friends. Everything in both your writing feels so lustful and wild, yet somehow completely outside the sensual.

Ocularis is another piece on surveillance as erotic. It’s more aggressive. Now the eavesdropping feels transgressive and dangerous, problematically pleasurable. I hear the narrator tell me about a childhood bully who called her a “rice head” on the bus. The story feels like a rant from a standup comedian, and I am entranced without really seeing the performer’s face. The woman remembers the surveillance camera documenting a racist picking on her on the bus. “Kent began his harangue on the bus, then he beat me up on camera.” This recorded act of violence, becomes the pivotal weapon against the bully. It is a GREAT STORY. We are watching buses in a garage depot and hearing this fantasy. We are listening, feeling fascinated without seeing the cause of our satisfaction.

Later, a woman editor falls in love with the man she sees on a surveillance camera. She knows him but he does not know her. Then there is the story of a small Asian teenager whose best friend was the largest girl in class. The large girl was attacked by a man who was a friend of the family. We hear this while we watch two good friends trying on clothes, the white girl asks for the opinion of the Asian girl. We hear about a young girl who carries a camera in her teddy bear. Counter surveillance services are discussed while we watch police at work. A young woman surveillance expert gets fired for a mistake she made on the job.

This movie has a sense of humor. It asks us if surveillance creates anxiety and boredom at the same time. Has all behavior become spectacle?

Finally, the sun is beginning to peek her head out from the lip of the horizon. Morning is knocking on the window, and I am watching Amaurosis. Amuaurosis is the word for vision impairment, especially when there is no obvious damage to the eye. All night, I have been inundated with cinematic reflections on the effects of blindness. I must admit I am feeling disconcerted by the light. I somehow find it difficult to remember that there may be something out there I would want to see. Then Tran introduces me to Nguyen Duc Dat, a blind classical guitar player to whom she has offered a flute in exchange for writing a song, or maybe for doing an interview. It appears to me a blissfully innocent arrangement that spins lovingly around a deep respect for the music this Vietnamese American makes with his instrument.

Tran begins this movie with a black screen as I hear a poem dedicated to childhood’s hour. “I have not seen as others saw… All I loved I loved alone.” These words are accompanied by guitar playing that I later realize might be Duc’s. Then I see a boy alone, walking the streets. The images are old, like a home movie, and the textures tell me this may be Vietnam. Tran then reveals the story of this blind musician through his own recounting, his philosophy of living in darkness, his commitment to active listening. He speaks eloquently about delivering speeches to an audience, really being heard and feeling more alive than ever, knowing that his words are able to open his mind to others. Duc articulates a concept of beauty in his blind experience that is so distilled and precise. He wonders if this connection between the lip and the ear, or between the guitar string and the ear, might be ruined by sight. Tran decides to illustrate this dichotomy, scientifically, with humor I believe. We are watching two large scale depictions of the cell, a biomorphic metaphor I would call it. One cell is imagery. The other is perception. Can a blind man appreciate the difference? Does it matter? Duc asks us: How far is close? He saw light as a child. Noticed that the sound of thunder had a fraternal twin, lightening born just moments later. In silhouette, Tran does her final interview. She breaks all the rules of good photography, covering the details of Duc’s face with darkness and allowing the sun to surround him with light.

I am almost finished watching ten years of Tran Kim-Trang’s opus on blindness. I listen to Duc speak of the ocean: it is big, it is horrible, the seaweed smells, the waves are music. This man has no need for blue. As you said “Night becomes a verb. I night.”

Lynne Sachs

2004 – 2021

Films by Tran Kim Trang:

Aletheia, 16 min, 1992

Operculum (cosmetic surgery on the eyes), 14 min, 1993

Kore, 17 min, 1994

Ocularis, 21 min, 1997

Ekleipreis, 22 min, 1998

Alexia, 10 min, 2000

Amaurosis, 30 min, 2002

—

Lynne Sachs was born in 1961, she is an American filmmaker and poet living in Brooklyn, New York. Her moving image work ranges from documentaries, to essay films, to experimental shorts, to hybrid live performances. Working from a feminist perspective, Lynne weaves together social criticism with personal subjectivity. Her films embrace a radical use of archives, performance and intricate sound work. Between 2013 and 2020, she collaborated with renowned musician and sound artist Stephen Vitiello on five films.

Strongly committed to a dialogue between cinematic theory and practice, she searches for a rigorous play between image and sound, pushing the visual and aural textures in each new project. Between 1994 and 2009, Lynne directed five essay films that took her to Vietnam, Bosnia, Israel, Italy and Germany – sites affected by international war – where she looked at the space between a community’s collective memory and her own perception. Over the course of her career, she has worked closely with film artists Craig Baldwin, Bruce Conner, Ernie Gehr, Barbara Hammer, Chris Marker, Gunvor Nelson, and Trinh T. Min-ha. In tandem with making films, Lynne is also deeply engaged with poetry. In 2019, Tender Buttons Press published Lynne’s first book YEAR BY YEAR POEMS

www.lynnesachs.com