DIANE SEVERIN NGUYEN

—

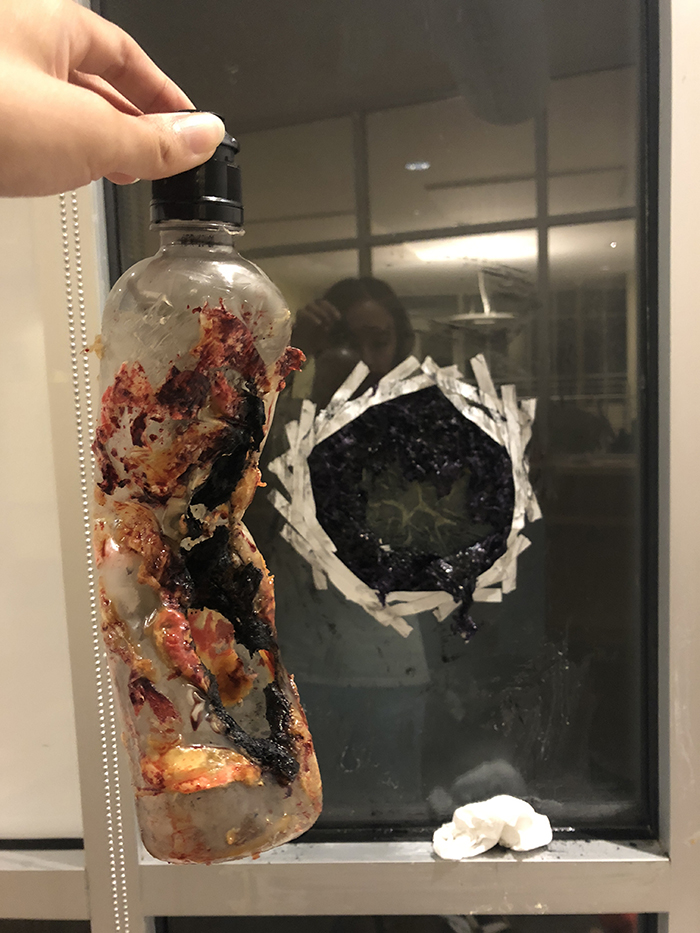

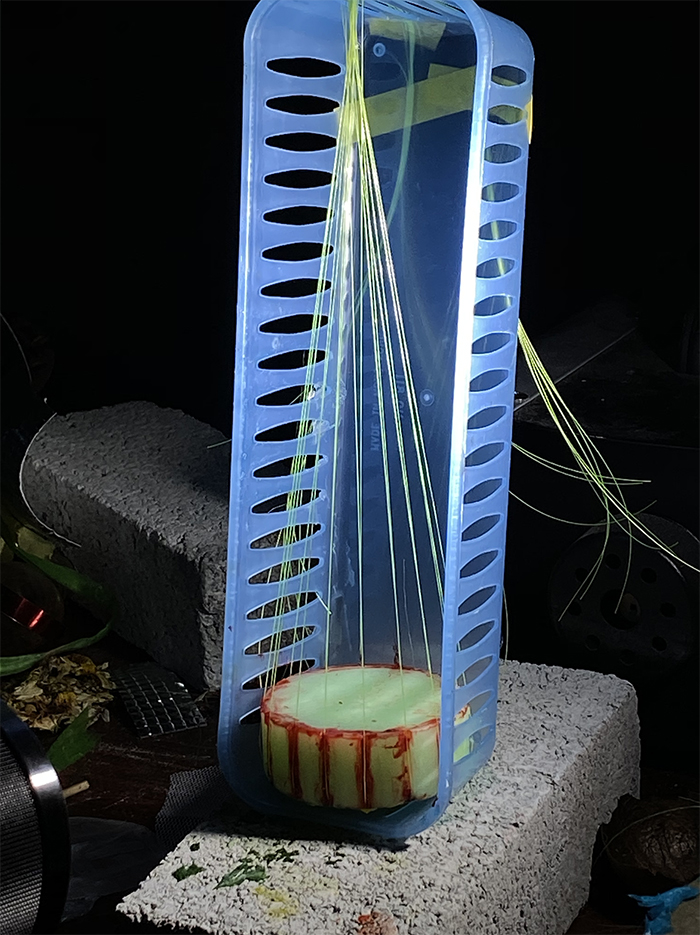

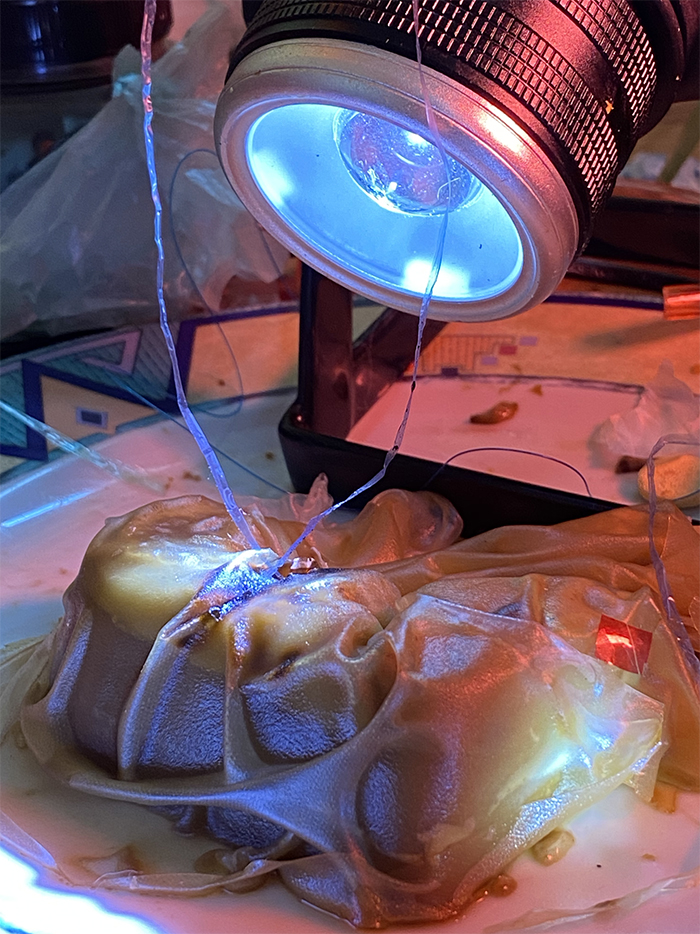

Diane Severin Nguyen is an artist who uses photography and time-based media to transform natural and inanimate objects into something uncanny. She currently lives and works between Los Angeles and New York. Nguyen earned an MFA from Bard College in 2020 and a BA from Virginia Commonwealth University in 2013. Her work will be included in the recent exhibition MADE L.A. 2020: a version, at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. She has had solo exhibitions at Bad Reputation, Los Angeles (2019) and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong (2019). Her film TYRANT STAR has screened at Yebisu Festival, Tokyo (2020); IFFR Rotterdam, Netherlands (2020); and the 57th New York Film Festival, New York (2019).