“I AM WHOLE” REFLECTIONS AND THOUGHTS ON MAKING NATURE SACRÉE IN TUNISIA BY MICHELLA BREDAHL IN CONVERSATION WITH ACHREF BALHOUDI

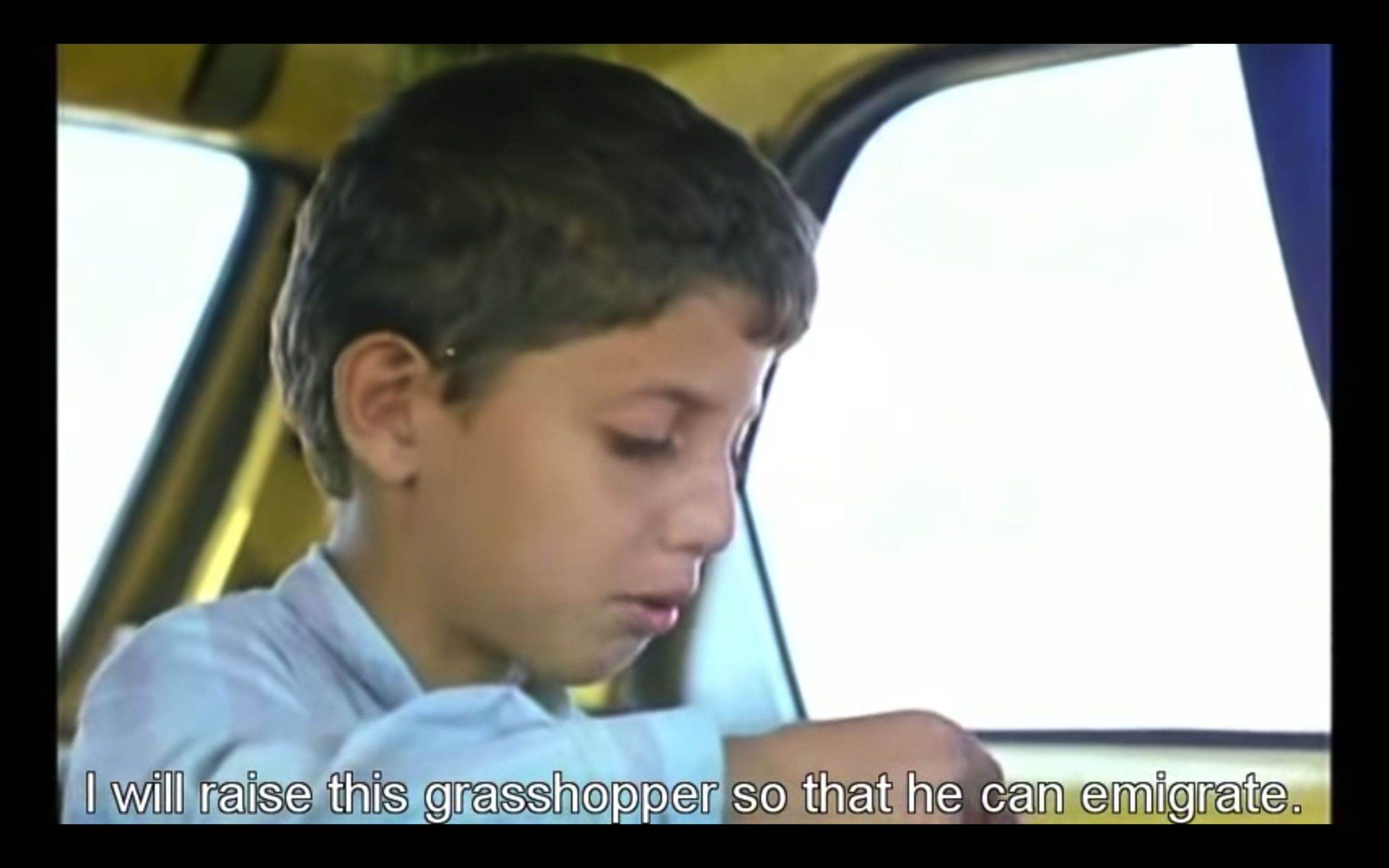

While I attended the National Danish Film school in 2018, a part of the program was to go and make a film abroad on your own. I was sent to Tunis in Tunisia. I had never been there before. Through Facebook I found a little room I could rent in Salammbo. It was late March, which is winter there and very cold at night. The guy I rented the room through told me that the bricks that the building was built with were made of a fabric to keep the heat out. With colder and colder winters in Tunisia, we were both freezing a lot at night, so he gave me several blankets that would keep me warm. I felt like I was sleeping outside some nights. I would keep all of my clothes on when I would sleep. The first week I spent a lot of time wandering around the streets. I noticed that there were a lot of wild cats everywhere. This was a very atypical view for me, because where I’m from in Denmark, most cats are domesticated. You would never see cats gather together in groups like this on the street in Denmark. It was like they were living parallel to the city and its people. The cats later came to play an important role in my short film, Nature Sacrée. I later met up with a Tunisian girl, Siryne, who I met at an exchange program at my school. She was a filmmaker too. We had become close friends. I went and stayed with her for a few days. She spoke with me a lot about not feeling able to express herself in her country. Most of her days, she spent time dreaming about living in Europe. She told me, “One day I will go to Europe and study, this is my way out of this prison”.

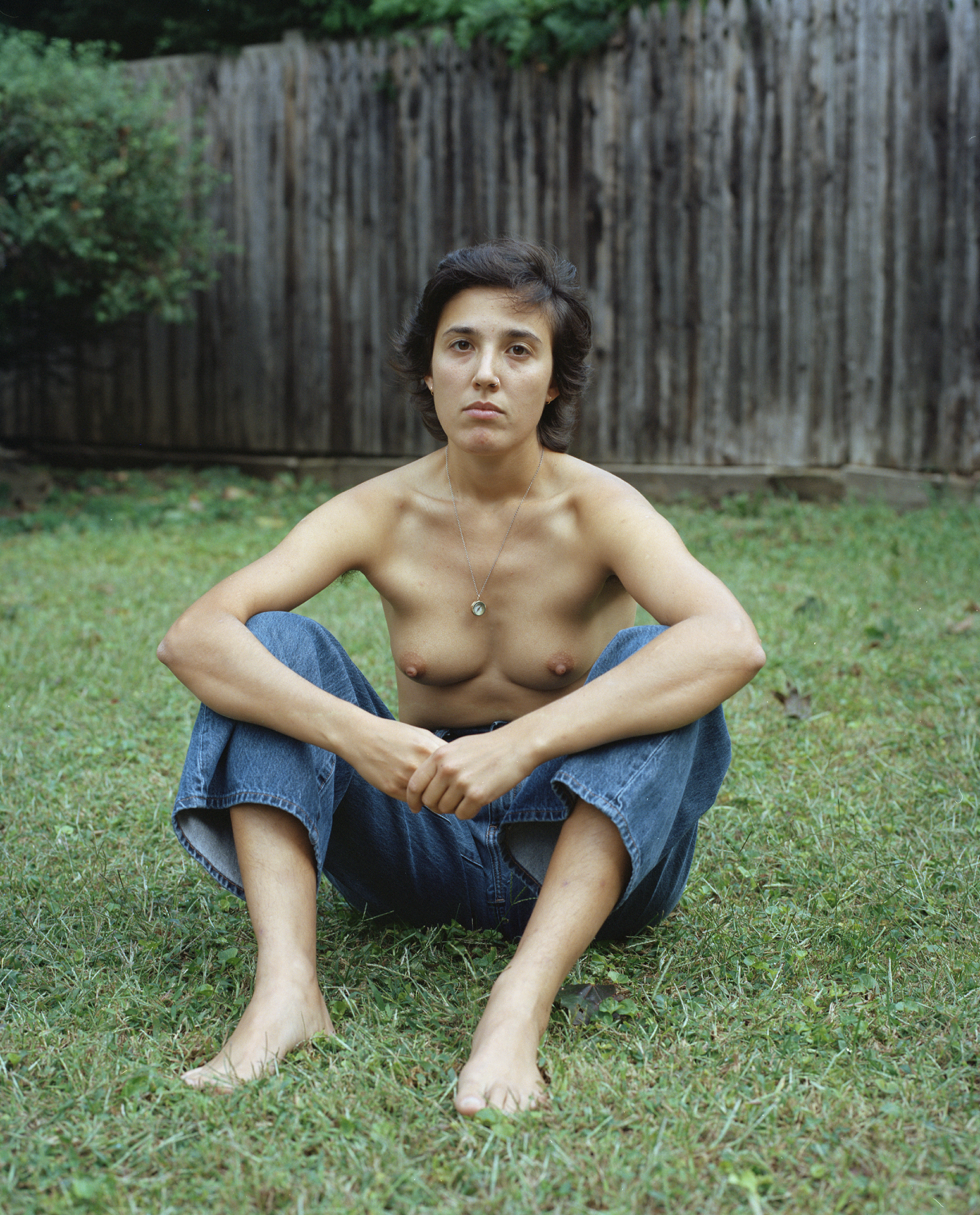

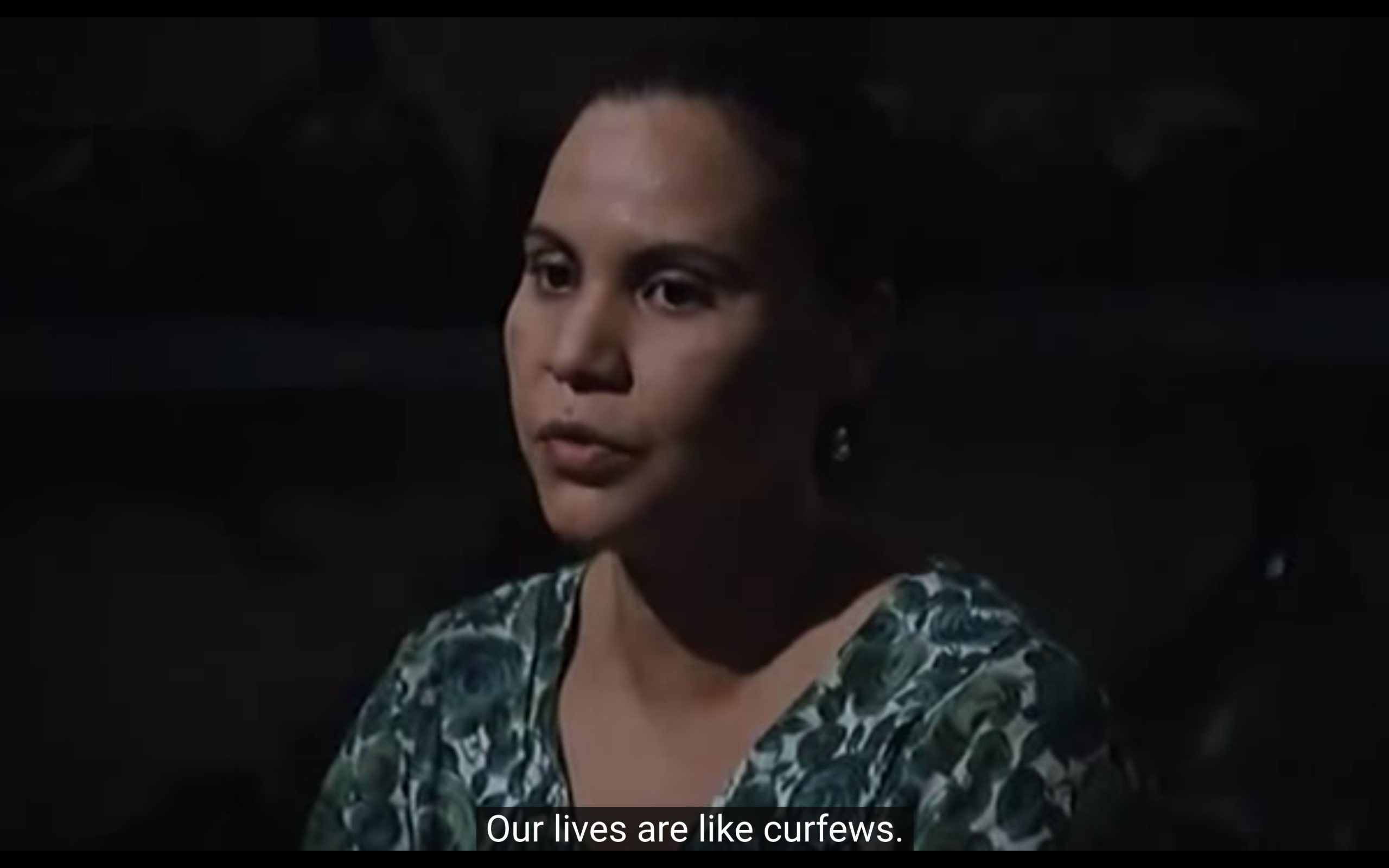

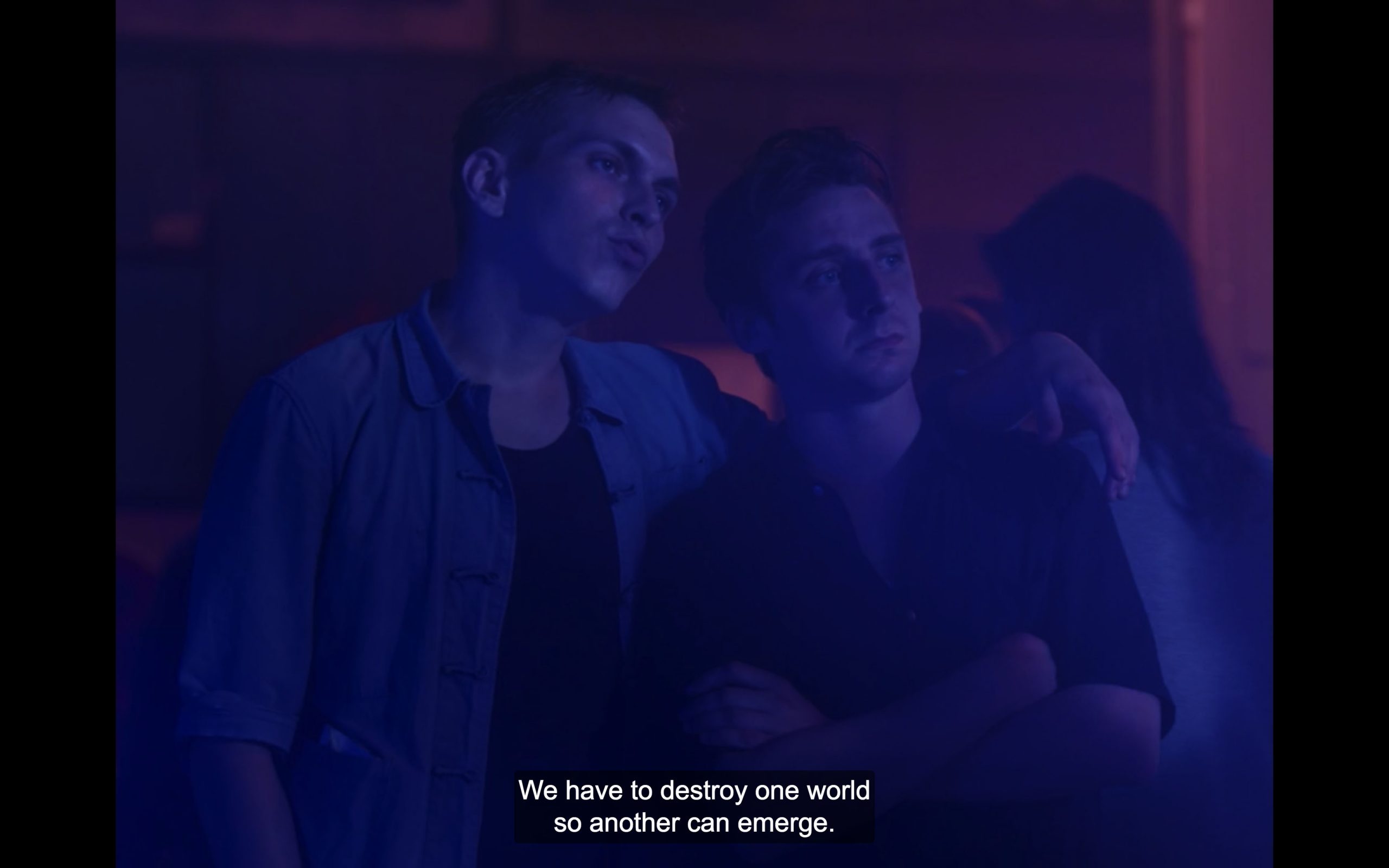

She explained to me that in Tunisia it is illegal to kiss on the street. Most cafés were only for men in her area. I had already noticed this myself. She was not allowed to bring any boys home or go out at night. Instead, she would rent a place to date a boy and meet them secretly during the day. I then had an idea for my film to create a space where she and her friends could move and express themselves in juxtaposition to the rules and the government, like the cats in the street. A place where you could kiss and study each other. A place where you could feel free to be yourself. She helped me get in contact with her friends, who said yes to be a part of it as well. We then found an apartment that we could borrow for it.

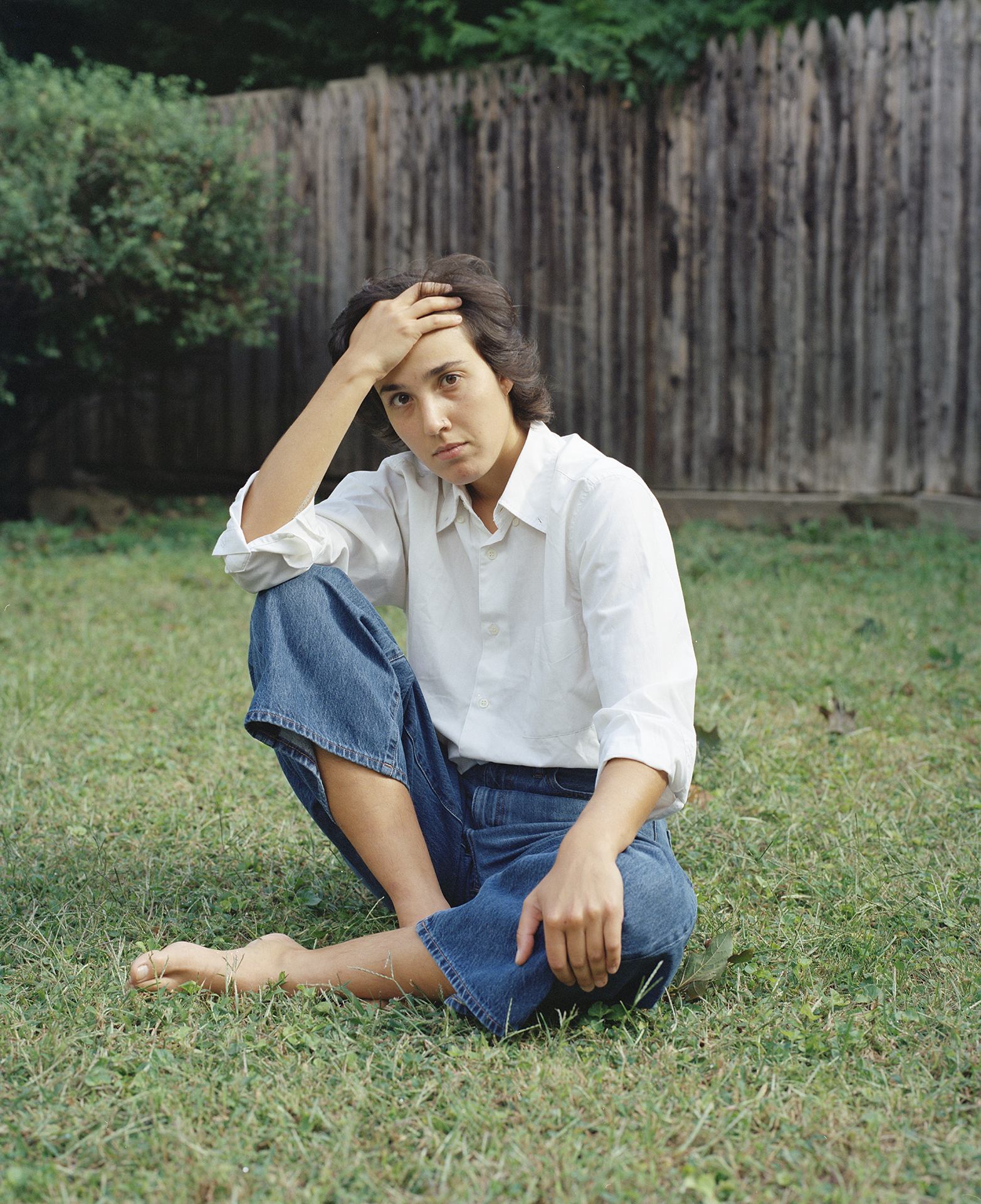

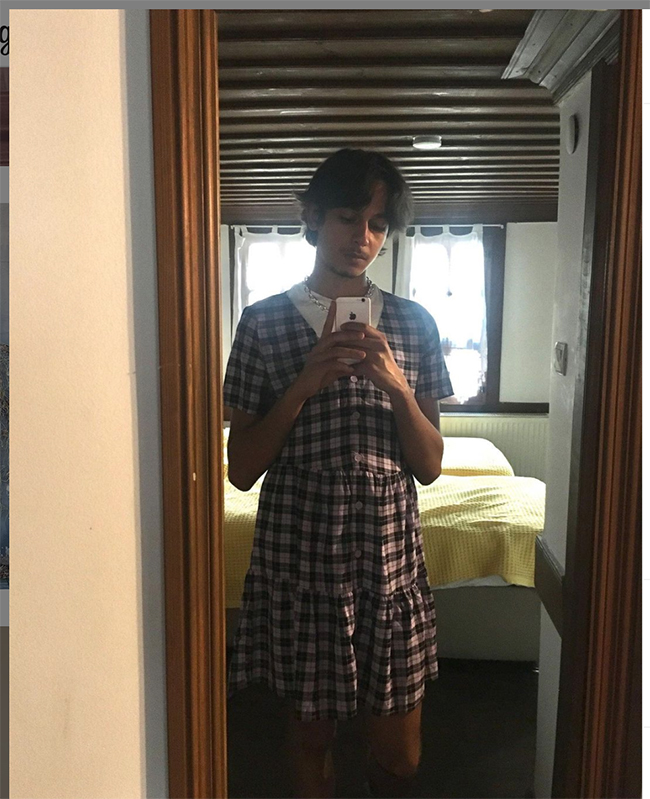

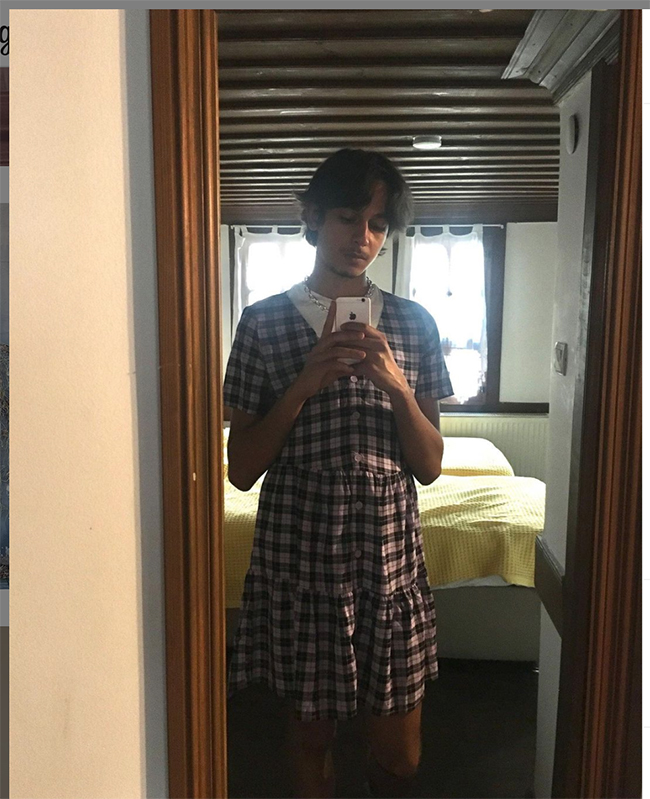

We all met on the street outside the apartment. I remember everyone feeling shy and excited at the same time. When we got up in the apartment, we were told we could only use the place for an hour. I remember feeling really nervous, because I knew that I was about to ask strangers to make out in front of my camera. We had all agreed that this was going to happen, but I was still nervous and worried about it becoming awkward or it not being a valuable experience for them. This is where I met Achref for the first time. He was very shy. He had this angelic way of moving his body around. He didn’t say much and had this expression on his face that would make anyone smile. I remember everything went so fast. We only stayed in the place for an hour. It felt really special filming them all. I remember my hands were shaking when I stopped the camera for the last time. It felt like I had seen something extremely real in all of them, and especially in Achref something magical appeared in front of us all. This memory has stayed with me up until today. After we left the apartment we found a little café, where we went and sat down and ate some food. I don’t remember what we ate or what we spoke about. I remember I shared my contacts with Achref and told him I wanted to see him again. He told me he wanted to move to Paris and work as a model. I told him I would help him if he came. We said goodbye and I didn’t see him ever again. We kept in contact on social media. I would often see things that he would post online that would touch me.

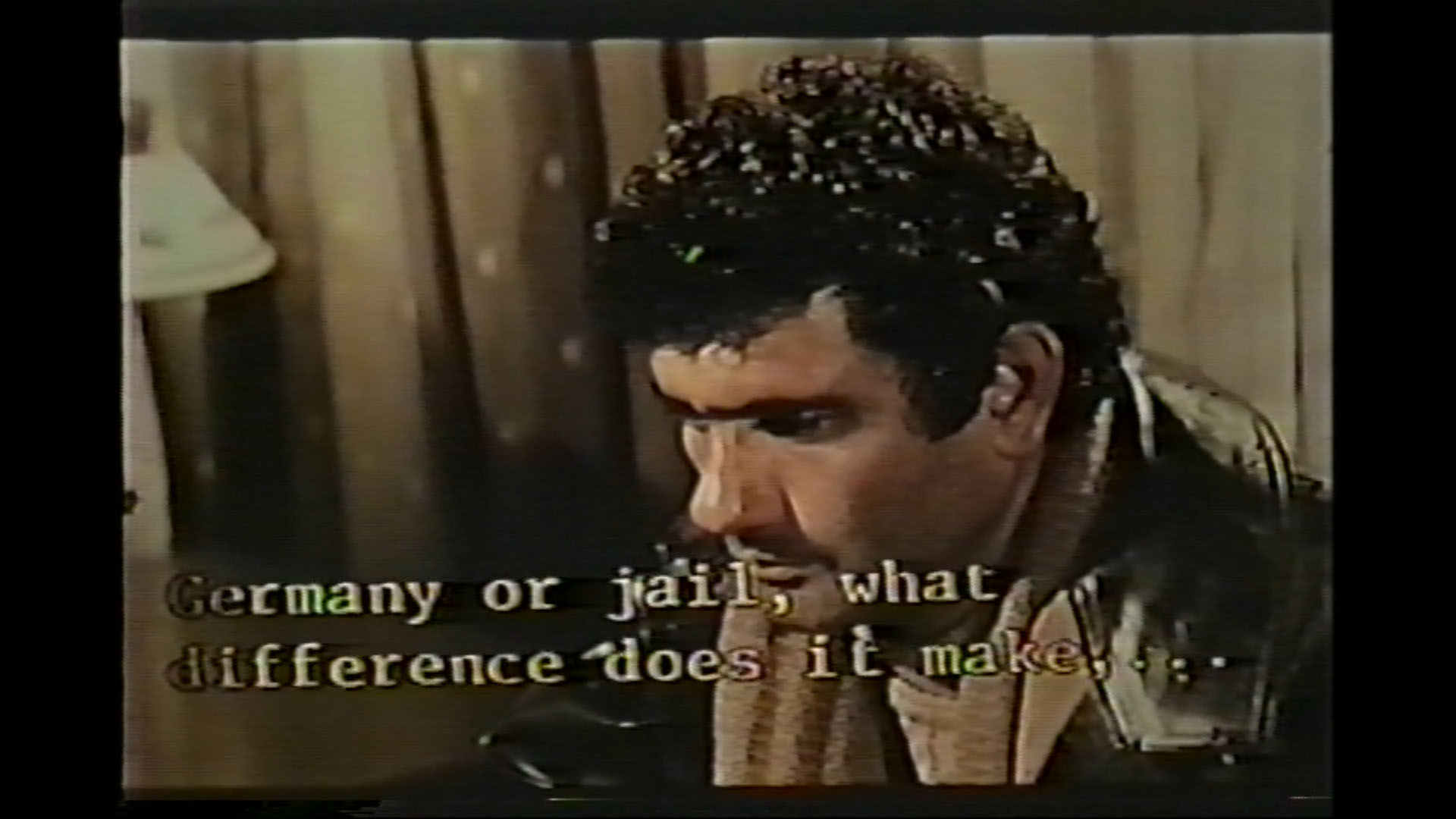

One day in December, of the past year, I read that he was happy to announce that he had got his residency in Germany. He was going to be able to be himself and love whoever he wanted without fear for his life. It saddened him to think of all the friends he had left behind and of the fact that people are still in danger, living in fear because of ignorance and violence. Their crime is love and self-expression. To my queer friends I say, I am sorry and we will as a community continue to keep fighting for change. Always.

When I was asked to contribute something for “This Long Century” I knew I wanted to share my experience with Achref and give him space to say something about his experience, his thoughts on the world and his current situation in Germany. It was two years ago, when I had filmed him and I had grown older, reflecting a lot about how I as an artist could give people in front of my camera space to express themselves, give them a voice and not only be seen through my eyes, through the camera. I asked Achref a week ago to watch the clip that I had filmed of him two years ago, to share with me his thoughts on it and let me know about his situation today. This is what he wrote:

“My only clear memory of Michella is of her sitting under the shade of a tree with Siryne eating a Shawarma sandwich in a coffee shop, wearing sunglasses in Tunis. She seemed distant, her camera felt like her way to grasp this world, to hold it, and to understand it. That’s how she exists in my mind. When I was filmed by her it felt like I was being seen for the first time. I didn’t need to speak. I was never good at that. Words seem to escape me and my attempts at communicating and connecting with others have always been lost, leaving my mouth only to find a barrier between myself and whoever I was trying to reach. It is probably one of the many survival mechanisms that I developed to hide behind, but for a moment sitting there in silence I managed to express what I was never able to. Through the lens of Michella, I was able to be free in this liminal space. Being queer and non binary was an offense in my country, something that can land you in prison, and definitely get you ostracized from the rest of society. This is where I found myself on the fringe craving freedom and belonging. Freedom for me is to be able to express myself without fear, to have the space to authentically be and for the first time this year I was able to experience that. It really hurts my heart that so many of my LGBTQ friends can’t experience it as I am typing this, and maybe never will. It really shouldn’t be like this. Coming to Germany wasn’t really a choice for me. I couldn’t live in fear in Tunisia anymore. It was eating at me from the inside and it felt as if I was holding my breath for too long. I needed freedom and community. I needed to breath. I thought I’d find that here, in Europe. I found safety, but I gave up on community. I didn’t think I would be confined by the Government to a small district for a year because of my nationality and to Saxony for a few years. I thought I’ll go to Berlin and meet other people like me, that I’ll belong, but instead I found myself alone and isolated, with a lot of trauma and emotional baggage to try to heal. I think I’ll always be on the outside looking in.”

The last conversation I had with Achref was on facetime, Friday the 18th of July. We spoke about freedom and what it meant for both of us. We both felt that social media is a strong weapon to connect between the people you relate with, a tool to find connectivity and light. We can create forces that can change things for us. I told Achref that I will soon be seeing him. My heart hurts to think of him alone in Germany. Instead I choose to think of that moment on the bed, when he felt free, and it seemed like his light came out and maybe for the first time we are looking at him from the outside.

Edited by: Tyí

—

Photography-based visual artist and documentary filmmaker Michella Bredahl (1988, Denmark) was educated at the Danish Photography School (2011) and the National Danish Film School of Denmark (2019). In her work, she focuses on certain groups of people and communities, such as teenage girls and mothers, capturing the vulnerability of her subjects. Her latest short film Chassé premiered at the International Film Festival Rotterdam (2020). She lives and works in Paris. Filmography: Nature Sacrée (2018), Chassé (2019)