LOVE IS FLEETING. PASSION IS FOREVER, JEAN-PIERRE BEAUVIALA

When asked to contribute something to this journal, I went back through my projects to see if there was something that might be appropriate to the forum and help me in some way rethink my process. I came across the beginnings of a project I had started with the inventor, Jean-Pierre Beauviala. In a notebook I had started for the project, I found the epigraph to this essay, a quote from JP when I had interviewed him. I was reminded of all the reasons I found him to be a fascinating figure: he was an engineer involved in an extremely structured mechanical device, he was a passionate human being who loved his practice, his friends, co-workers, and lovers, and he was committed to re-envisioning society to make room for these interests. For him, work and love were the same thing. I rethought my own relationship to cameras in general and my Aaton and the films I made with it. I also thought about the theme of love in my films, one that, in retrospect, was the undercurrent of everything I’ve done, but that I rarely spoke about and always submerged beneath a rigorous structural approach.

In 1994 I made my first film, Khalil, Shaun, A Woman Under the Influence, a combination of disfiguring makeup tests and a reworking of the last scene of Cassavetes’ film. Having never made a film before, I hired a camera operator to take care of the technical requirements. I found the physical nature of film provided a very satisfying structure to work with. The size of the magazine provided very distinct and limited time segments based on the repeated opening and closing of the shutter, and the fixed lenses defined the image in a similarly limited and structured way. I also discovered I was much more effective in front of the camera with the subject, moving back and forth between the view behind the camera and in front of it, communicating physically. What I had originally seen as a handicap (my inability to operate the film camera) turned into a positive way of engaging the image for twenty plus years.

My next three films, Goshogaoka, Teatro Amazonas and No, were all defined in part by the technology that produced them (the 400-foot magazines of 16mm cameras, the maximum time you can get out of a 1000-foot 35mm magazine shot on a 3-perf camera, and the optics of a normal lens’ field of view). But, looking back, each of them really was about the people in front of the camera and my relationship to them. Goshogaoka became something of a community project over the three months I spent working with the girls and their families and, after the project was completed, I continued to stay in touch with many of the girls years later when they had their own children. Choreography, meanwhile, worked as a great device to help me negotiate my relationship in front of and behind the camera. It gave a structure to those relationships that mirrored the repetitive, mechanical operations of the camera. One might miss the tender relationship between the husband and wife in NO and the months I spent getting to know them and their land because the rigorously structured optics and choreography of the film are foregrounded.

It was in the midst of the NO project that I began researching 16mm cameras to make a film of children in a small rural town in the foothills of California’s Sierra Nevada mountains. If I brought a camera person or a team of the size I had worked with on the previous three films, I knew that it would alter the results. There had to be a level of intimacy in the process and, since the film would be shot amid the landscape, the camera had to be fairly mobile. I was looking for a model that was easy to operate and had a large viewfinder for the kind of precise framing that had been an important part of my practice. I spoke with filmmakers, tried out their cameras and read everything I could about different models. I was discouraged by the complexity of most cameras and how it was impossible to frame an image due to their small viewfinders. Eventually, my research led me to the Aaton camera and then to its inventor, French engineer Jean-Pierre Beauviala.

The Aaton was completely different in its approach. It was designed to be nimble, quiet, easy to use and repair, yet logical and precise in every way. It was designed for filmmakers and not camera technicians. I purchased an Aaton LTR-7 with a 25mm Zeiss lens and two 400-foot magazines, and it was perfect for the project that I had bought it for.

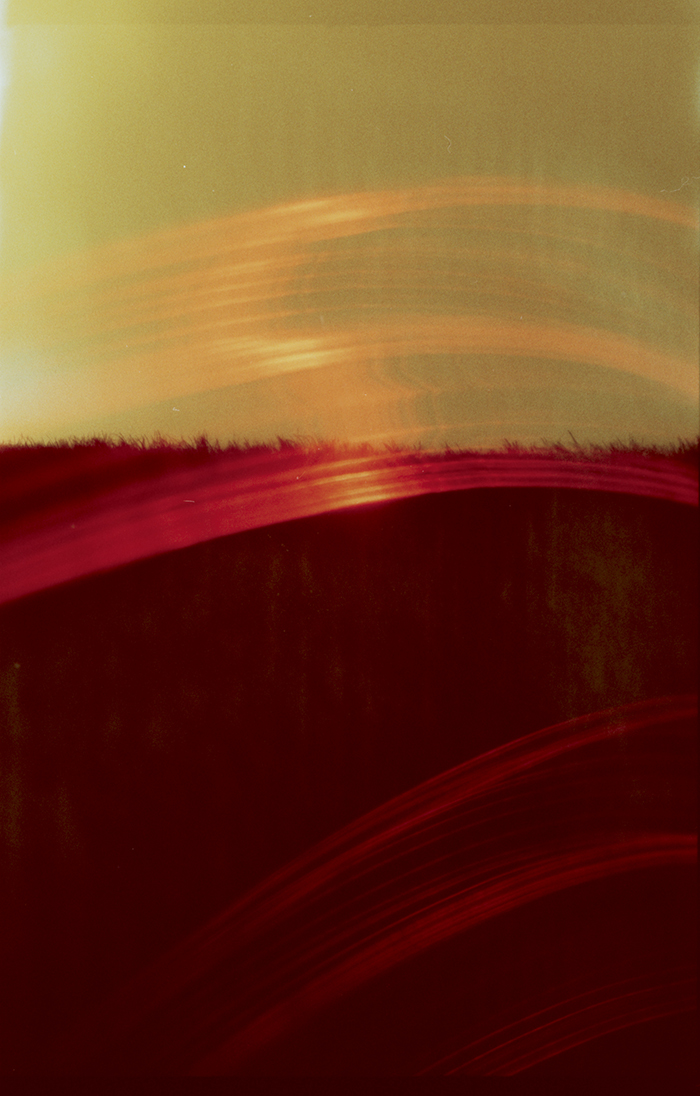

Shot over the course of three years, Pine Flat was different from anything I had done. It took years to make and I got to see many of the children grow up in front of the camera. We formed a strong bond that grew even tighter than the community I formed during Goshogaoka. Although the twelve ten-minute takes again used the maximum footage a 400-foot magazine could produce, each shot was set in a different landscape and planned out with my subjects based on activities they enjoyed. Together with the children I scouted locations, lugging the camera up hills, to waterfalls, down river embankments, in rain, snow, and hot summer days. Over those years I grew to love my Aaton. Its relative mobility allowed us to film in truly beautiful and somewhat remote landscapes. Its quiet mechanics allowed for intimate shots with very simple sound recording. Its large viewfinder and diopter allowed me to precisely frame each shot and show the children what the image was going to look like. They became experts at knowing the frame they were performing in and how the light moved within it. I loved the daily labor of loading and downloading the film and cleaning the camera after each shoot. The camera’s physical attributes—the way it sat on one’s shoulder like a cat, the smooth, hand-carved walnut grip—were unique. For me, the Aaton was a truly remarkable machine.

Through my camera research and in the production Pine Flat, I became more and more interested in, and curious about, the inventor of my camera. In the winter of 2002, I was invited to Harvard University to screen Goshogaoka and begin conversations about an exhibition. My initial proposal was an exhibition engaging Beauviala’s archive. I decided to visit Grenoble for a week, meet Jean-Pierre, interview him, and approach him about developing a project.

He was incredibly welcoming. In my first encounter with the archive, everything was dusty; letters and drawings were rotting, prototypes were haphazardly thrown in boxes. It consisted of boxes and boxes of important but unorganized history. JP was more interested in the invention he was working on in the moment than looking back at his past, but he humored me by going through boxes and introducing me to his team. What struck me about all this material was the very personal nature of it all. I loved the many humorous advertisements he made and the films he shot of his girlfriends, always while testing inventions. In many ways they were like home movies, recording the history of his love life, yet each one was shot in service of his camera and recorded the history of its development and life in the world. For example, I remember a girlfriend, naked in bed, reading a book about philosophy or mathematics. He worked like an artist, engaging the world around him. There was no rigid separation between work and life. I wanted to make a film out of his tests, a film about his love life and his passion for cinema. I imagined an ode to love constructed of bits and pieces gathered from the archive, a history of both camera and passion.

He was resolutely local and thought of his manufacturing site as a response to urbanist critiques of the 1960s. His laboratory/factory was located in the center of the city amongst a set of storefronts on either side of a small street close to shops, cafes, and restaurants. JP prided himself on joining his collaborators daily in the shop windows on both sides of Rue de la Paix. People would always tell him he was wasting his time (and money) going back and forth between the locations. He insisted upon a resistance to a functionalist approach to production, saying, “We will never leave to an industrial zone, the so-called functional, which translates to me as car, work, sleep. At Aaton, a lot of people come by bike or foot.” He liked the glass storefronts and believed that passers-by should be able to look in and see what was being built and that workers should have an engagement with the street and be part of the fabric of the neighborhood.

Among the founding principles of Aaton was that labor should not be invisible. On my visit, he introduced me to everyone who worked for him. He was not interested in the normal hierarchies of the workplace. He claimed, “decisions here are the responsibility of everyone.” At Aaton, the organization of the workplace and the products they created were political. The simplicity of the Aaton cameras allowed a more flexible, mobile kind of filmmaking and revolutionized documentary film. Not surprisingly, there was a humanism present in everything they did. For example, in Jean-Pierre’s office, and where possible in the rest of the site, there was no artificial lighting. He told me, “when the light leaves us, that is the end of the day.” Although, at the time, he was working on groundbreaking digital cameras and sound recorders, he had an appreciation of the analog. He asked me not to use a recording device when interviewing him, saying the words had go straight through my hand.

As we poured through the boxes of materials, we encountered a virtual history of the last half-century of French cinema. For instance, I found a wonderful original negative reel of Godard with a color chart on the banks of a river. The film was a product of a lengthy collaboration between him and JP. Godard’s wish was that the camera would fit in his glove compartment. JP was so pleased that I liked the footage, he casually ripped off a foot of the film and handed it to me. I had to refuse his offer and admonish him for not giving these materials their due. On another occasion he showed me the first synch-sound test that worked. My memory of the test is that it was shot in a mirror, reflecting the camera, his little son, Julien, sitting on a table, and the scene of cars going by outside the window.

His collaborators included many of the figures I saw as role models and they would visit him in Grenoble to test new equipment and repair their trusted cameras. On a later visit to Grenoble, Raymond Depardon was there because his camera had fallen in water while he was filming. That same visit I photographed a copy of the LTR made of tin soda cans by participants in one of Jean Rouch’s African films. JP had never really thought of these bits and pieces of his life and research as interesting to those outside his close circle of friends, but I knew that this history needed to be preserved. I was introduced to someone at the French Cinematheque, and eventually the institution was able to purchase the archive in its entirety.

In the end, the interview never took a form one could read, and I never got to make the film I envisioned. After the Cinematheque had purchased everything, my experience with the material was different. There were rules in place limiting interaction. A great deal of the archive had been moved to Paris and JP had a different sense of his and the archive’s importance. It was clear, at this point, that there was no way to move forward with my project.

Yet many of the ideas that my encounter with JP inspired became part of my later work. My next project was about labor and I thought a lot about Aaton’s windows onto the street as I researched and filmed Lunchbreak. Exit, a document of workers leaving the Bath Iron Works shipyard, was filmed with my Aaton, as was Double Tide, a document of a woman clam digger on a rare occasion of two high tides in one day. In all of those three films I was hoping to address the invisibility of labor. Double Tide had a particularly satisfying rhythm of shooting, downloading and reloading the magazines, sleeping three or four hours and then repeating the whole process each day for a week. For each 45-minute shot we had four magazines. The film would not have been possible without the ease of replacing those magazines quickly.

Jean-Pierre’s ideas about the vibrancy of city life were present, as well, when I filmed Podworka in the Polish city of Lodz in the summer of 2009, again on an Aaton LTR. The last time I used my Aaton was for a short film I made in the summer of 2014 with one of the children I met in Lodz and kept in touch with, Milena. Milena had lost both her parents and was living in an institution when we discussed making a film about her life. We ended up recreating the final sequence of Truffaut’s 400 Blows on the Polish Baltic coast. If this was the last time I ever used my Aaton, it would be a fitting end because it really was a work of love.

In 2009 I also started a project that would allow me to work with an archive as a kind of portraiture. The project involved working with the archive of Noa Eshkol, a choreographer in Tel Aviv. Together with her collaborators I was able to honor her life and activities in a project that included archival materials, two film installations, and a suite of photographs. In many ways Eshkol’s activities mirrored Jean-Pierre’s. She was a maverick who insisted on her own way of doing things and was surrounded by a group of devoted collaborators. As I met the women of the Eshkol foundation a year after her death, they lived a fairly communal lifestyle in their workdays. Eshkol was also an inventor, having invented the only system of movement notation able to account for all animal locomotion, and she kept her process close to her daily life. It was only fitting, then, that the sound recordist for the films I made with Eshkol was a huge fan of Aaton’s Cantar digital audio recorder.

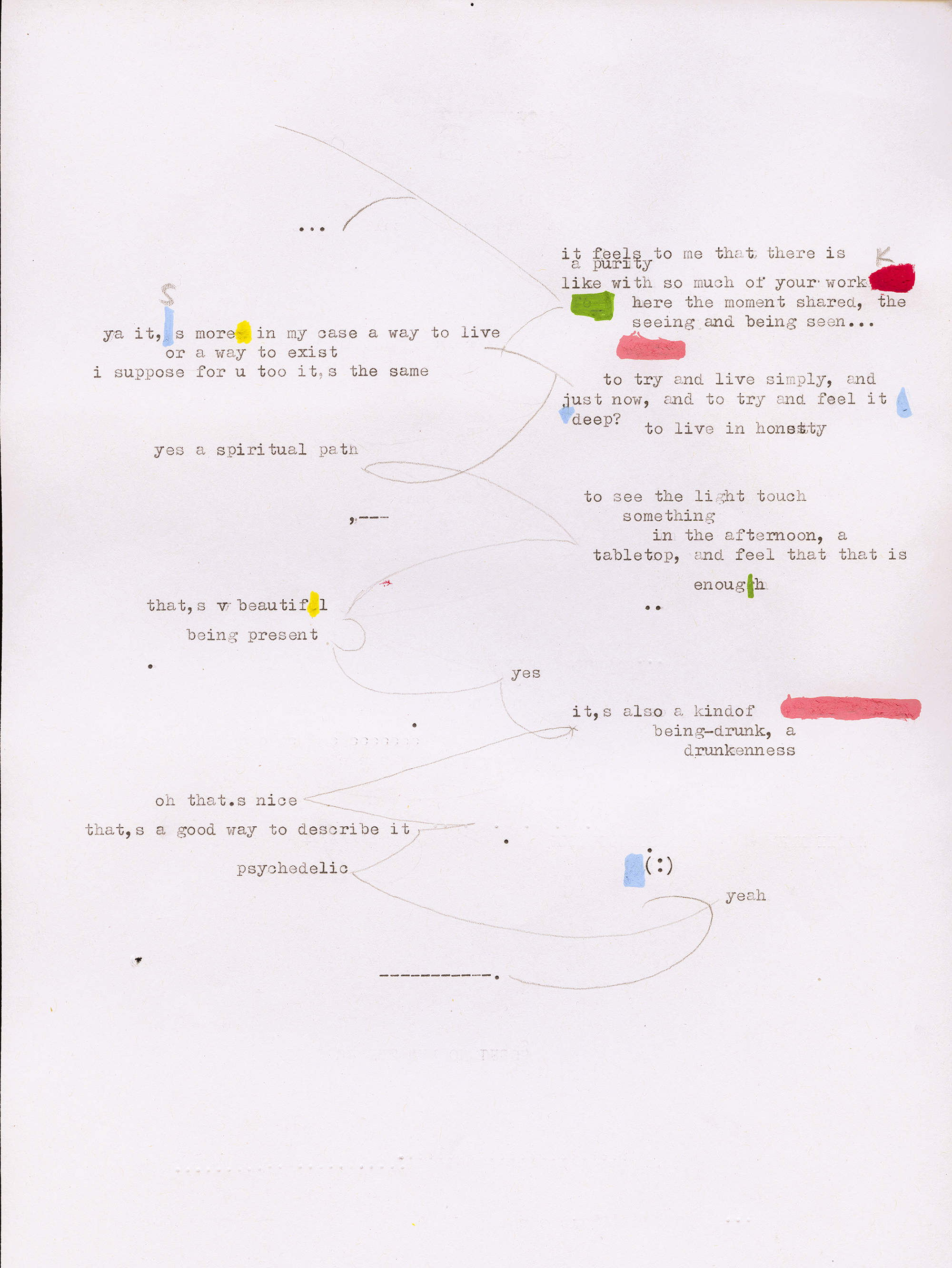

As I reflect back on the connection between the work I had envisioned with the Beauviala archive and what I was able to do with Eshkol, it strikes me that film is a medium of love. When I encounter compelling objects, landscapes or people, I use film to share them. As a way of avoiding the sentimental or nostalgic, I often submerge these relationships under a structure that might allow a viewer to experience them anew. There were seven dusty wire spheres hanging in the corner of Noa Eshkol’s dance studio. I asked the dancers what those sculptures were, and they replied that they were just diagrams Noa had used and had been there as long as anyone could remember, so the dancers had stopped noticing their presence. Each sphere was a model for describing the movement of a limb on the axis of a joint. We took them down, polished them, and photographed them in a studio rotating like a spinning dancer. Jean-Pierre and his archive were lost subjects for me. Perhaps it would be better to think of it as a lost love.

[First published in Les Saisons Cinema Journal]

Sharon Lockhart

cat-on-the-shoulder, for Jean-Pierre Beauviala, 2011

20×25 inches

chromogenic print

—

Sharon Lockhart was born in 1964, in Norwood, MA. She lives and works in Los Angeles. Educated at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, CA and the San Francisco Art Institute, Lockhart teaches at CalArts in Southern California. Working with communities to make films, photographs, and installations that are both visually compelling and socially engaged, Lockhart’s practice involves collaborations that unfold over extended periods of time. Her practice often involves architectural elements, extensive periods of research, and longterm relationships with her subjects and collaborators.

www.lockhartstudio.com