MARK RAPPAPORT

Wednesday, March 13th, 2013CHILDREN OF PARADISE, CHILDREN OF LIFE

— Let the pro-lifers and anti-abortion crowd argue about when life begins. I’m much more interested in an even thornier issue—when does nostalgia begin? How old do you have to be before you can be nostalgic about something? Can you be nostalgic for experiences you never had, or memories that weren’t yours, or a history that belongs not to you but to others? In other words, is nostalgia fungible? Let me go back to the middle of the last century. I am about 10 years old—maybe a little older, probably a little younger. In the bottom drawer of the fake Chippendale secretary that everyone had at that time, mixed in with the family photo albums, are a few copies of Life magazine and The New York Post, which in those days, was a liberal paper. Huge headlines. STALIN DIES. ROSENBERGS EXECUTED. It was that kind of family. The newspapers didn’t interest me very much. It was the issues of Life that always got my attention. There were all those pictures. Sometimes, on very rare occasions, let us say a rainy, wintry afternoon when I was home alone and filled with undefined feelings of re-visiting a past I never had, I would swaddle myself in a linen shroud of the recent past which I had no memory of and knew nothing about and I would go through the old issues. There was something very visceral about it. It was like exploring an attic, replete with spider webs, that filled your nostrils with the smell of dusty wood, or descending into a rank musty damp cellar. I was especially taken with one issue of Life in which there were pictures of a film I never heard of, but I liked the title. Children of Paradise. The images were magical and stuck with me. There were, strangely enough, only of scenes taking place on stage. I remembered very vividly photos of Arletty, as the statue of a muse, lyre in hand, while Jean-Louis Barrault, in his Pierrot costume, is asleep on the bench next to her, dreaming of her. It occurs to me now that those stills were probably the reason I loved the idea of theater, if not theater itself. You probably know the stills as well, even if you’re not familiar with the movie. The same stills even today are invariably used whenever the film is revived or written about.

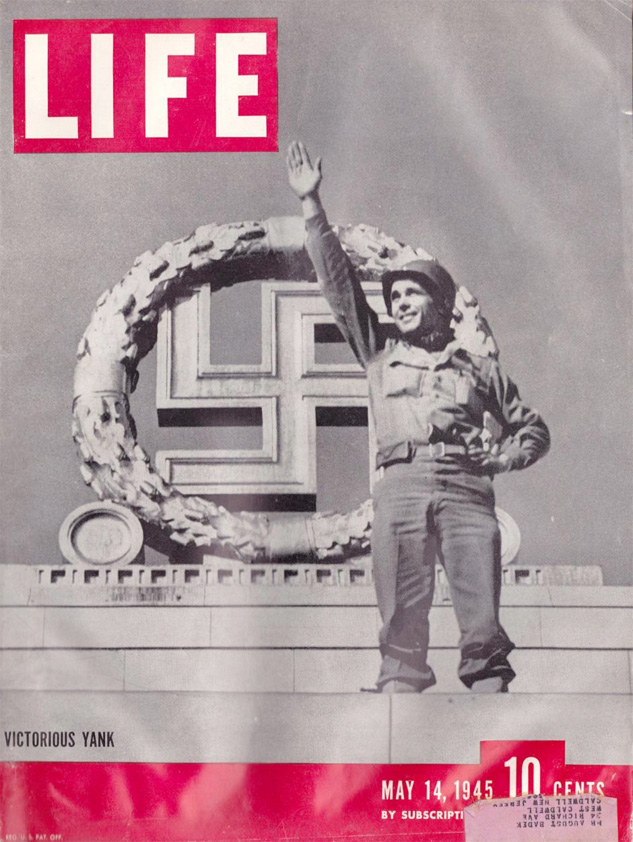

Decades later, after my mother’s death and all the artifacts in the house were long gone, I wanted to get that particular issue of Life. It cost $54. If you want to run your nostalgia to ground, be prepared to pay for it. The issue with the photo spread of Children of Paradise was dated May 14, 1945. The reason my parents kept it is because the issue documented the surrender of Germany. A historic issue. The cover picture is of an American soldier in Nuremberg standing in front of an ornate sculpture of a swastika wreathed in a garland of sculpted flowers. He is in the stadium of Nuremberg, mise en scène courtesy of Albert Speer and immortalized, and lasting longer than the Thousand Year Reich, in a film by Leni Riefenstahl. The American soldier is raising his arm in a mock “Heil Hitler” salute. I remember this picture.

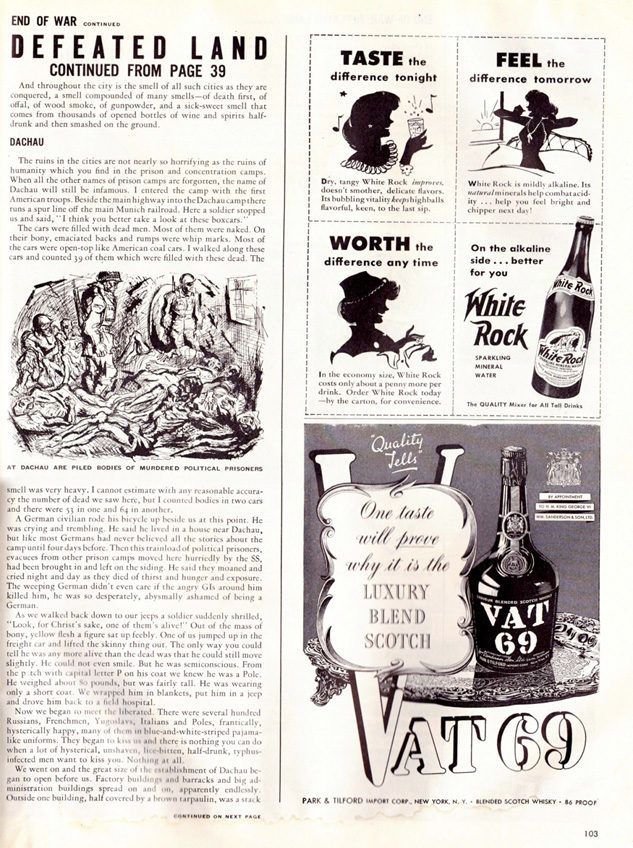

It was taken by Robert Capa, whose name I didn’t know as a kid but was a famous photo-journalist. I recently found out that he had a very torrid affair with Ingrid Bergman. It wouldn’t have meant anything to me then and it probably doesn’t mean very much to anyone now. Their incompatible lifestyles apparently were the model for the couple played by James Stewart and Grace Kelly in Rear Window, another factoid that probably has no special resonance for anyone but interests me. There was also a full- page photo of an Allied prisoner of war about to be decapitated by the sword of Japanese officer. I remembered that, too. It’s a classic of documentary war photography, although at the time it was just a news photo bringing the horrors of war home to your living room. There were also articles about Germans committing suicide rather than surrendering—with photos. An article about Dachau—with charcoal drawings. Actual photos would have been too upsetting for us Life-rs. There was more than that, too. A picture spread of a new Broadway musical called Carousel. Pictures of Mussolini’s death, all of this smashed cheek-to-jowl with ads for consumer products. The Dachau article was the centerpiece of a triptych, flanked by advertisements of men in underwear, home appliances for women, shaving cream, liquor, and so on.

The juxtapositions seem breathtakingly grotesque and insensitive to us today (or do I mean incredibly contemporary?) and without any intention of ironic counterpoint, even if you wanted to be or could be ironic about the war and concentration camps. Unless you think, of course, of today’s newspapers which similarly ignore the casually brutal juxtapositions of articles about poverty in Third World countries and wars around the world yoked together on the same pages with ads for women’s fashions and luxury goods.

The trivial, jokey ads, the unmitigated horror contained within the context of the articles themselves all indiscriminately thrown together, each democratically vying for attention, suggesting that life, as well as Life, is a grand smorgasbord in which one can pick and choose but no priorities are assigned in the placement or sizes of images. Post-modernism before the fact—trash-mashing the ghastly with the frivolous, history and horror trumped by consumer products, the grim and the soothing, the high and the low together, sleeping in one Procrustean bed.

Speaking of which—at some film festival or other, I met a German filmmaker, now dead, who called himself the Little Godard. He wanted to know if I knew anyone who had a VHS of Holocaust, the TV mini-series which first put Meryl Streep’s cheekbones on the map. He wanted to show the series, complete with commercials, in Germany. I also recall watching a TV movie by someone I knew about white American journalists—what else?—in Ethiopia taking pictures and writing articles about starving children. In between the segments, there were commercials for Weight Watchers and other weight-loss programs. To quote that great American philosopher, Jack Parr, “I kid you not.”

Back to Children of Paradise. Movie stills offered a promise that the films themselves could only partially measure up to, where a moment could last forever, unlike its screen counterpart, a fleeting elusive image that disappeared before you could fully possess it. Until the movie itself was seen, they not only stood for the movie, they were the movie. Maybe if the other photographs of that particular issue that I would look at so bemusedly on a chilly afternoon had had as strong an impression on me, I might have been interested in becoming a historian or a still photographer. But it was the images of Children of Paradise that held me. And still do.

So, how is it that these same publicity stills, used over and over again, a tiny part of the movie that is frozen in amber, comes to replace the movie because it’s nailed into your brain and when you think of the film, the first thing that comes to mind are the stills that are permanently engraved there? Why do these stills, a handful of images from a film that contains around 260,000 of them (the movie is 3 hours long), printed with ink that dried almost 70 years ago, in a magazine that hasn’t existed for decades, copies of which are scarcer than hen’s teeth, still feel like precious slivers of the true cross?

—

Mark Rappaport was born in 1942. Rappaport is a filmmaker, whose films include; THE SCENIC ROUTE(1978), IMPOSTORS(1979) and, more recently, ROCK HUDSON’S HOME MOVIES(1992), and FROM THE JOURNALS OF JEAN SEBERG(1995). A collection of some of his writings’ THE MOVIEGOER WHO KNEW TOO MUCH, is available as an e-book. Rappaport currently lives in Paris.