Growing up, my father owned a travel agency in New York called Merillon Travel. Merillon coordinated all of the flights for Major League Baseball’s National League umpires. This provided my dad with special access to Mets games, which came in handy as a kid, as the Mets won the World Series in 1986, when I was ten and cared about baseball. More importantly, Merillon supplied my family with discounted airline tickets, which allowed me the luxury of visiting Europe for the first time at the age of eight.

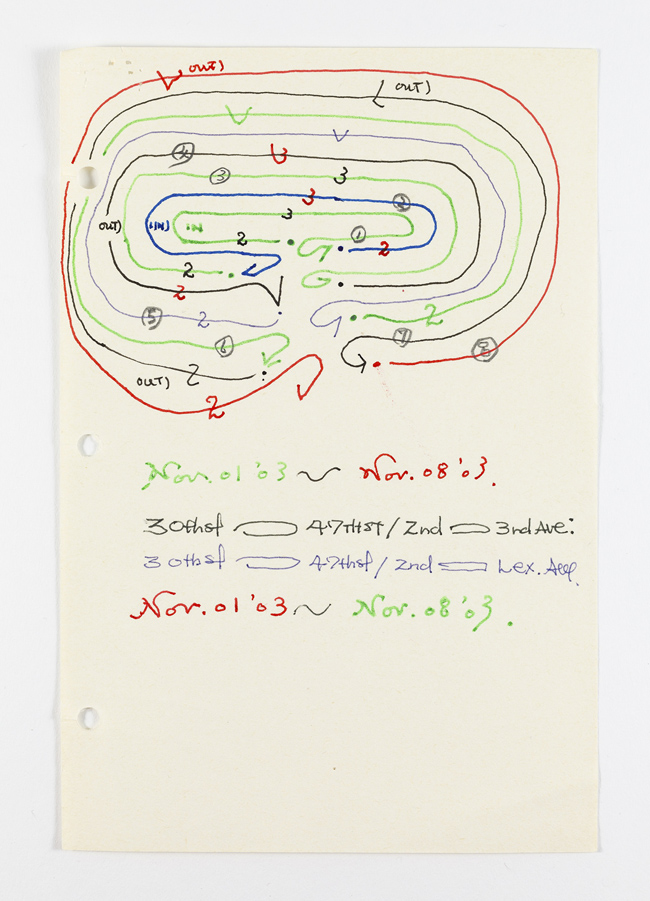

In 1988, my father sold the travel agency to one of his employees and opened a bar-restaurant in up-and-coming Long Island City, Queens. Unlike Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Long Island City had a much slower process of gentrification. Coupled with the economic downtown of 1987, the bar closed after six years of business. My dad went bankrupt and was hired by a former regular as the trucker for a now-defunct art-moving company called Modern Art Services. My father was born in Brooklyn and raised in Queens, which helped in navigating the city, and he perfected the timing of what became known as his “no-lunch lunch”—his unrecorded lunch hour. I don’t remember what the connection was, but Modern Art Services often employed Irish and Scottish artists who were in New York for their studies or for art residencies. My dad worked on his truck with an Irish artist named Gerard Byrne. Gerry’s first significant video, from 1997, is called “Why it’s Time for Imperial, Again” and it costars my father as the former Chrysler CEO Lee Iacocca in conversation with an actor portraying Frank Sinatra. The script for the video came from an advertisement that ran in National Geographic. The intro text to this ad stated that Iacocca and Sinatra sat down for a conversation on July 18, 1980, to talk about Chrysler’s 1981 luxury car, the Imperial. Gerry’s video went on to be screened at various international venues and returned to New York for inclusion in a group show titled “The American Effect” held at the Whitney Museum in 2003. I was in grad school at Columbia University at the time, and was inspired by the way Gerry had used a seemingly inconsequential advertisement to perfectly frame the conservatism of 1980s America.

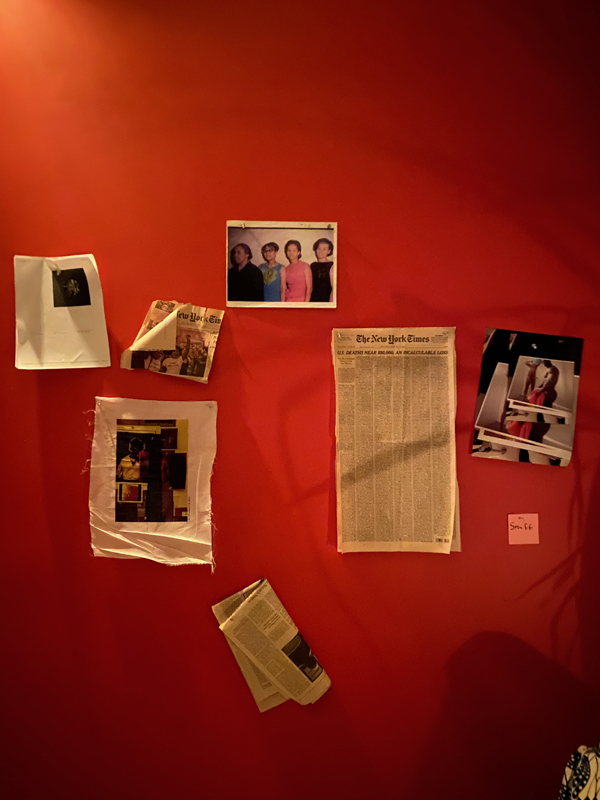

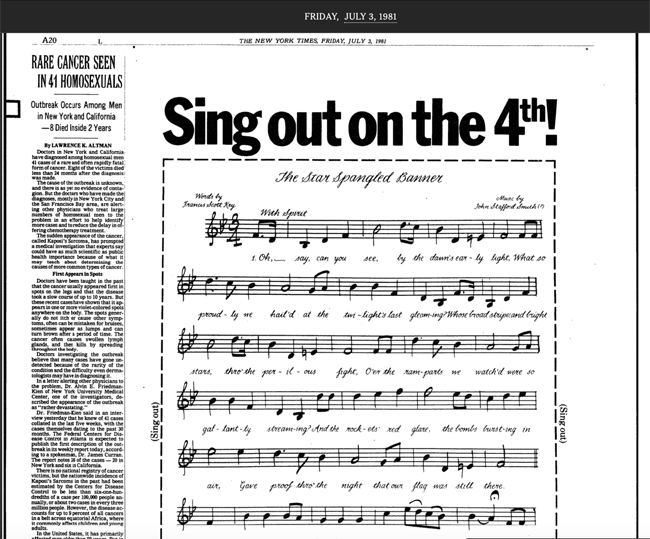

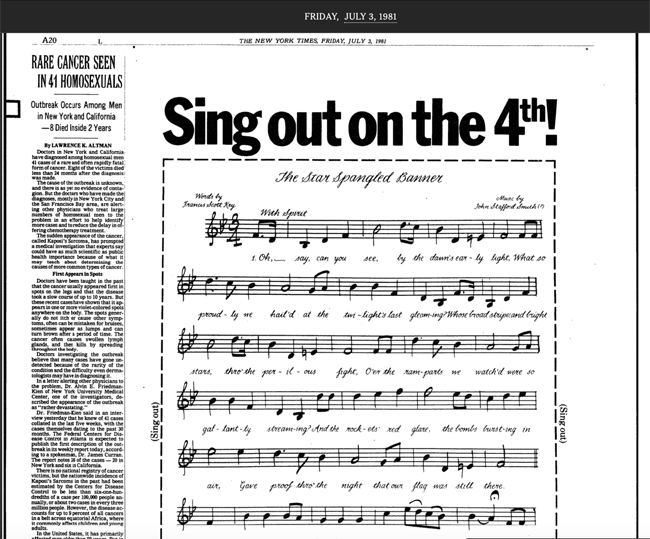

On July 3, 1981, a year after Frank and Lee talked about the perks of that year’s Chrysler Imperial, the New York Times ran its very first article about the “Rare Cancer seen in 41 homosexuals” that would later be known as AIDS. The article mentioned that most of the patients resided in New York or the San Francisco Bay Area. It quoted Dr. Alvin E. Friedman-Kien of New York University Medical Center describing the appearance of the outbreak as “rather devastating.” That same week, the Federal Centers for Disease Control, in Atlanta, published its first description of the outbreak. Dr. James Curran, a spokesman from the center, was quoted as saying that “there was no apparent danger to non-homosexuals from contagion.” As the death toll continued to grow over the following year, the crisis did not receive significant coverage. It met with utter disregard from the Food and Drug Administration and President Ronald Reagan, as was glaringly evidenced by an October 1982 interview with White House spokesman Larry Speakes:

Q: Larry, does the president have any reaction to the announcement –– the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta, that AIDS is now an epidemic and have over 600 cases?

Mr. Speakes: What’s AIDS?

Q: Over a third of them have died. It’s known as “gay plague.” [Laughter] No, it is. I mean, it’s a pretty serious thing that one in every three people that get this have died. And I wondered if the president is aware of it?

Mr. Speakes: I don’t have it. Do you? [Laughter]

The first Times report on the emergence of AIDS appeared on page A20 to a near-full-page ad for Independence Bank that featured the lyrics to “The Star Spangled Banner” to be sung the following day to celebrate the Fourth of July. Independence was my bank at that time; I can remember the passbook my mother gave me as a child. Every time I would deposit birthday or holiday money, the bank teller would stamp it. This passbook is long gone, but I remember that it was close to the size of my passport and had the same pleather exterior. The correlation between income and literal mobility was made clear.

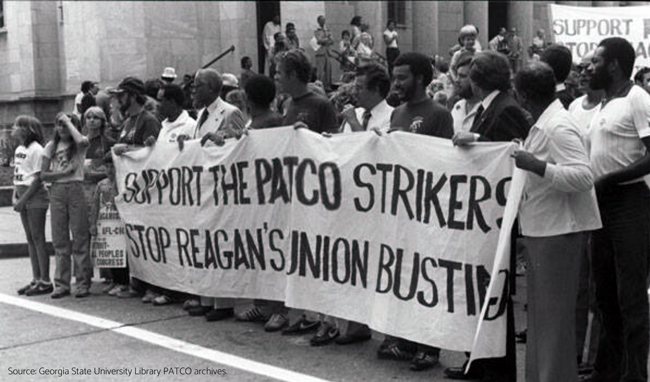

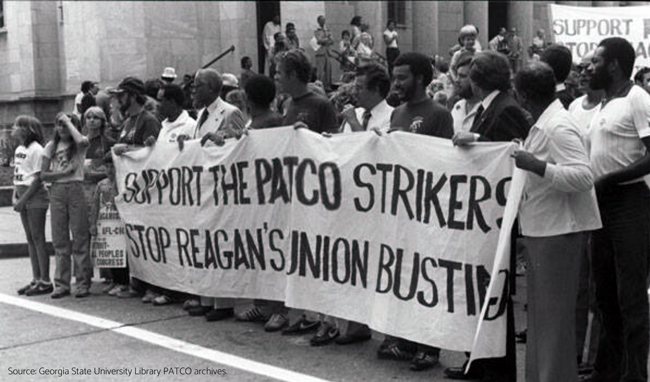

On August 3, 1981, exactly one month after the Times’ story, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Association striked, leading to an unprecedented firing of federal employees by President Reagan. After they ignored his decree to return to work, Reagan fired 11,345 striking air-traffic controllers. This firing is regarded as the single most public and impactful attack by government on organized labor in this country. Thirty years later, on February 7, 2011, the Republican governor of Wisconsin, Scott Walker, pulled out a picture of President Reagan and said to his advisers, “You know this may seem melodramatic, but thirty years ago, Ronald Reagan had one of the most defining moments of his political career, not just of his presidency, when he fired the air-traffic controllers.” Now it was time to follow his example. Walker went on to present a bill that would remove public workers’ right to participate in collective bargaining via their union representatives. This, as author Joseph A. McCartin points out, misrepresents Reagan’s full handling of the PATCO strike and also ignores his earlier stint as president of the Screen Actors Guild, where Reagan led a strike in 1952, and his signing of collective-bargaining legislation in California when he was governor in 1968. In his book Collision Course, McCartin writes about how the emergent social conservatives used PATCO as a sign of a broader cultural shift. Conservative columnist George Will wrote that “in a sense, the ’60s ended in August 1981.”

My first and only tattoo, on my right wrist, is of an airplane. It was a gift for my twenty-fourth birthday from my first love, Boris. The airplane came from a par avion stamp, and I got it because I felt like my life in New York was beginning and also as a physical reminder to always travel. In 2013, I had my first solo exhibition in Lisbon, Portugal. Email correspondence and intermittent phone calls with a friend’s mother, Helena Cardoso, helped to generate the content of the show. In 1968, Helena became a flight attendant for TAP, the national airline of Portugal. At that time, Portugal was under a dictatorship and few people were traveling, let alone a woman in her early twenties. Helena fell in love with Rio, Angola, which was then a Portuguese colony, and New York. She traveled to these cities over the next twenty years, before retiring in 1988. I keep returning to the thought of being in the air for that many years and seeing cities change both incrementally between each trip and significantly over decades. And I love thinking about how much time she had been in the air in total. Based on the travel time from New York to Lisbon, I guessed it to have been a full year—Helena says it was approximately 19,000 hours, or just over two years. Over two years, hovering between locations and their ever-changing population and political landscapes.

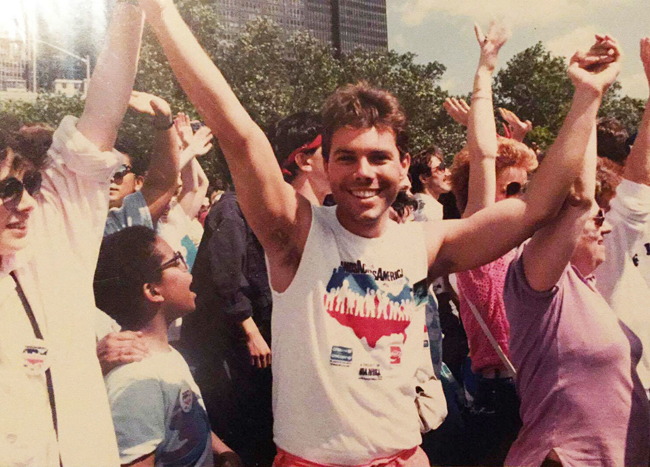

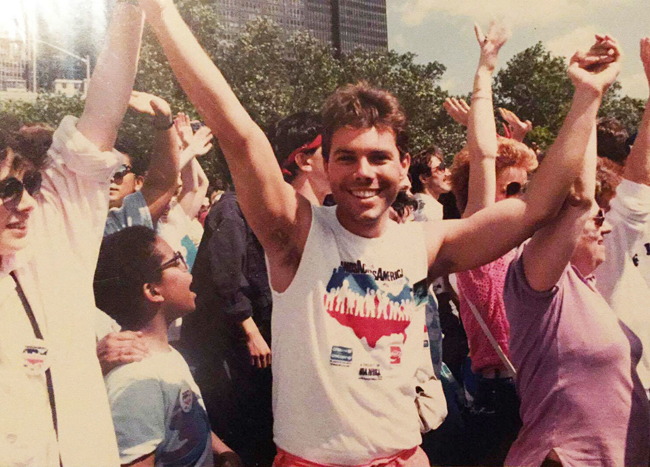

In 2007, I was commissioned to make an artist book by the New York nonprofit Printed Matter. At the same time, I was invited to have my first solo exhibition in Los Angeles. These two projects developed in tandem. I knew that I could not have a solo exhibition on the other side of the country, in the fall of 2008, without addressing the impact of the second Bush administration, the fractured state of this country, and the forthcoming presidential election. While thinking about the potential content for both book and exhibition, I remembered “Hands Across America.” A national event that occurred on May 25, 1986, in which people joined hands between Battery Park, Manhattan, and Long Beach, California, in support of America’s homeless population. Although it was a failure as a fund-raiser, millions of people participated, including President Reagan and First Lady Nancy. I found this event fascinating for a variety of reasons, foremost among them that Reagan and his administration worked meticulously to undo social programming for the impoverished of this country. Secondly, the AIDS crisis, by this point, had entered the public consciousness, but Reagan did not speak about AIDS until May of 1987 and American citizens were far from establishing countrywide support for AIDS advocacy. In fact, the same year Hands Across America took place, the Supreme Court held up Georgia’s sodomy law, “dismissing the notion of constitutional protection for gay sexuality.”

In the summer of 2007, I made a cross-country trip along a route loosely based on the original Hands Across America map, meeting with mayors between New York and New Mexico and making casts of their hands. I stopped in many small towns as well as larger cities, including Minneapolis, Oklahoma City, and Santa Fe. It was a fascinating way to see parts of the country I had never traveled to before and to get a sense of the local and civic levels of government in this country.

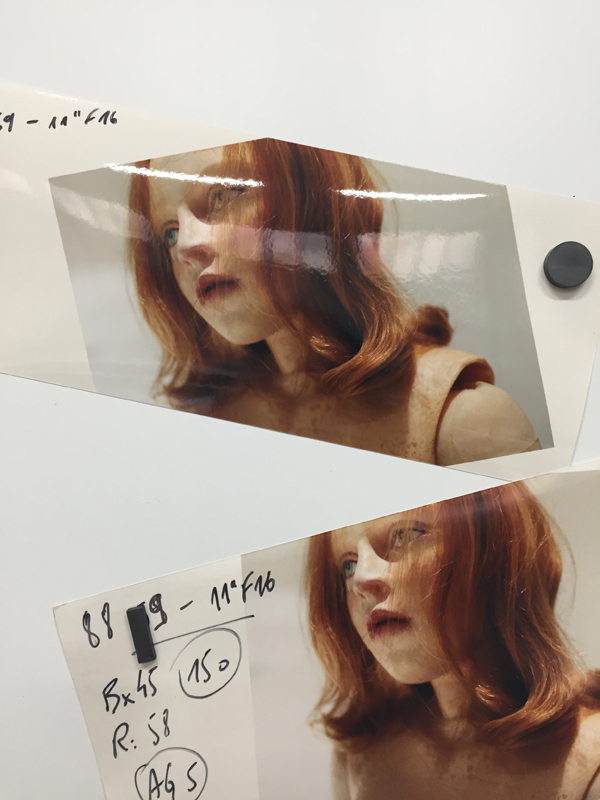

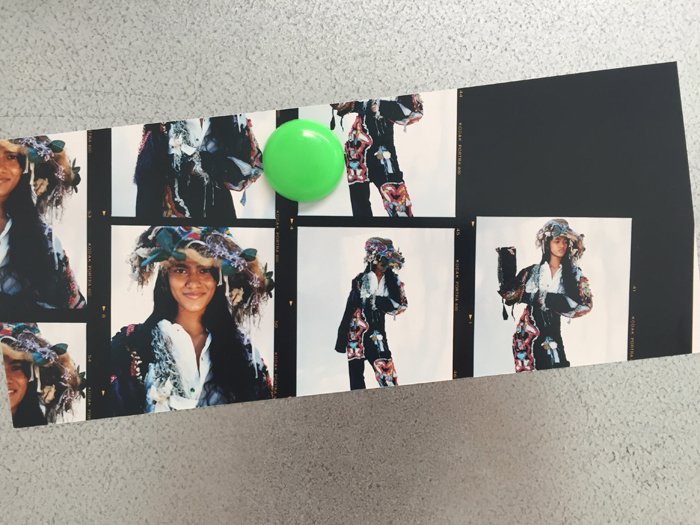

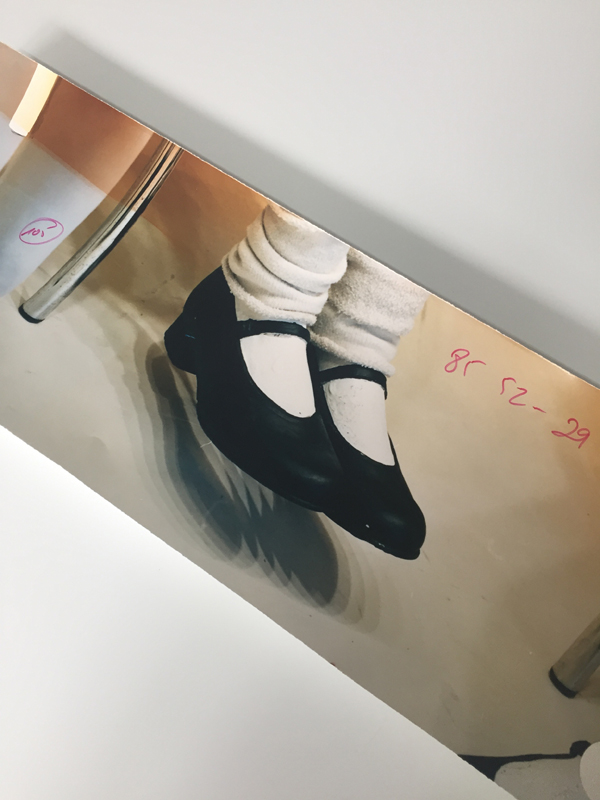

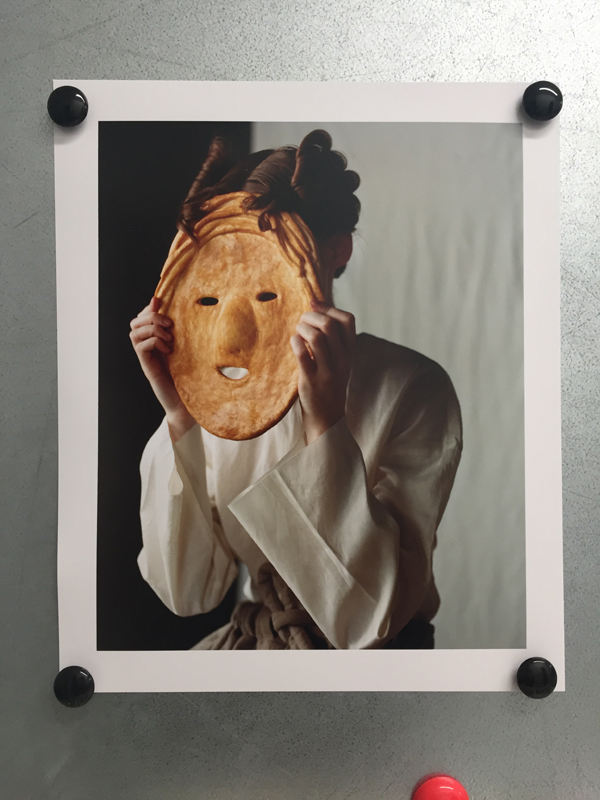

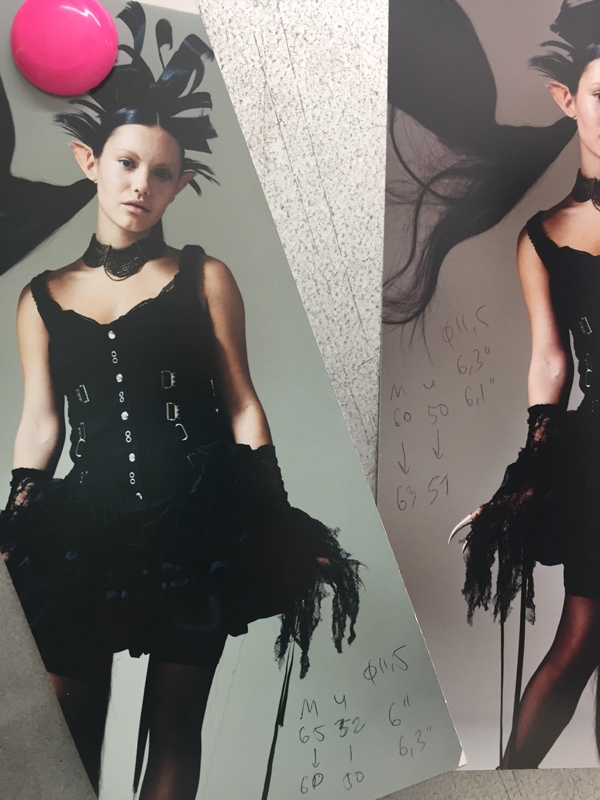

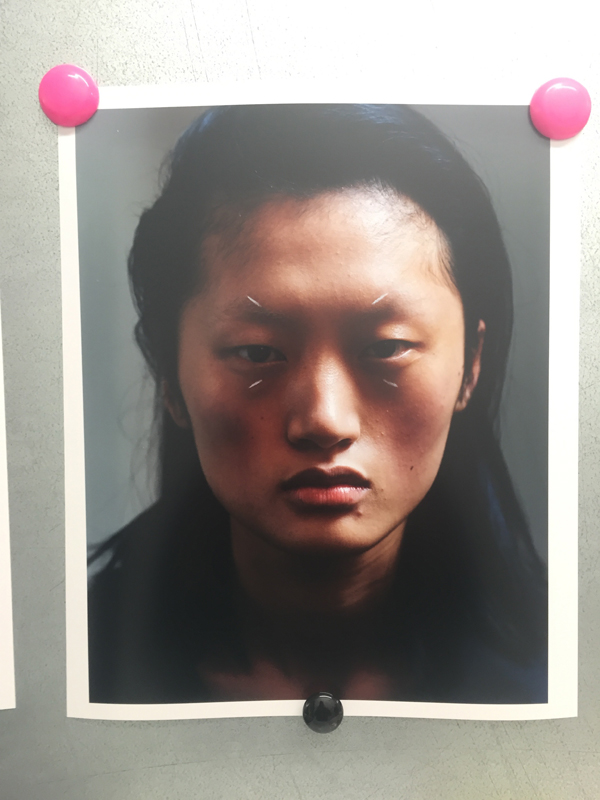

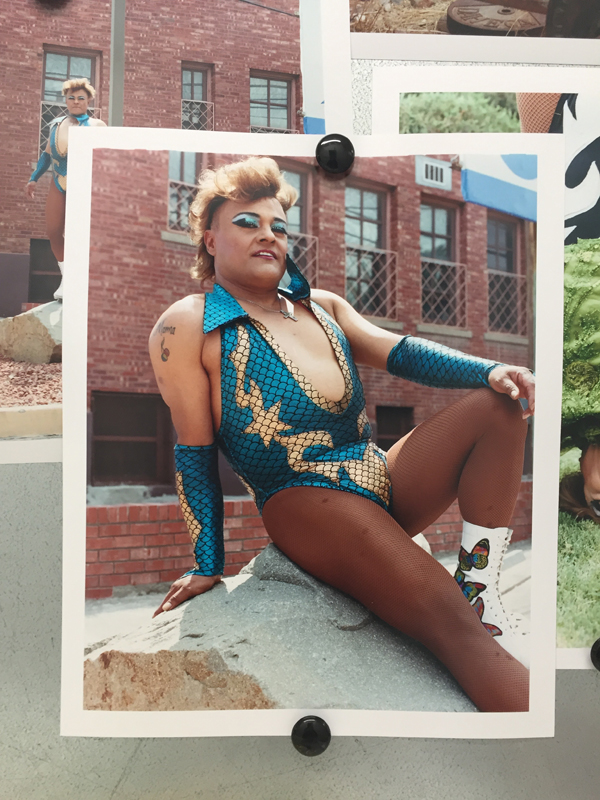

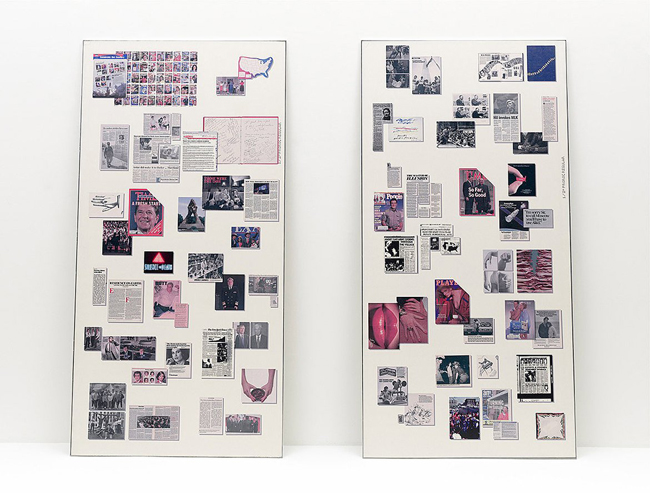

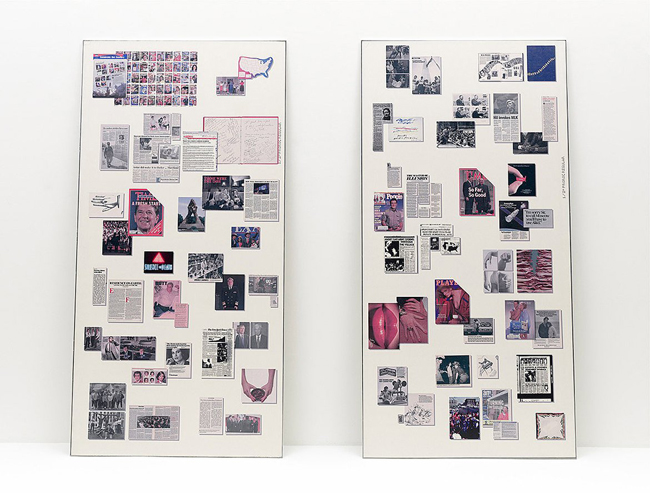

After completing this road trip, I realized I did not want to make a book or show that revolved around Hands Across America and became focused on the similarities I found between 1986 and the lead-up to the election of 2008, in which Reagan emerged as a totemic figure invoked by both Republicans and Democrats as a politician whose legacy we should uphold. I conducted interviews with artists Mark Dion, Daphne Fitzpatrick, Elizabeth Peyton, Collier Schorr, and T.J. Wilcox and reprinted writing by Gregg Bordowitz; all had graduated from School of Visual Arts in 1986 and 1987. Additionally, I photographed twenty-three arts-related students who were born in 1986 and about to finish college at New York–area schools in 2008. Generationally, I fall between these two groups, and I was interested to hear about the older artists’ earlier lives in New York and their activism. I was also interested to hear about the frustration they had with what they viewed as apolitical twentysomethings. I then asked these younger participants how they would respond to this portrayal of their generation.

Last fall, I released a book called 1996 that looks back on that year to assess the rightward shift of the Democratic party under the two-term presidency of Bill Clinton. AMERICAMERICA served as a template for this book, for which I interviewed Becca Albee, Malik Gaines, Chitra Ganesh, Pearl C. Hsiung, Jennifer Moon, Seth Price, Alex Segade, and Elisabeth Subrin, all of whom finished undergrad in 1996. Again, I photographed a group of people born that year. I’m closer in age to the ninety-six graduates, and like them, I also voted for Clinton when I first came of voting age.

—

Matt Keegan lives and works in New York. Keegan’s work has been widely exhibited in venues including the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts (Cambridge, Massachusetts), Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Grazer Kunstverein (Graz, Austria), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim Museum (NY, Bilbao and Berlin), The Kitchen (NY), The Art Institute of Chicago, and the New Museum. In 2019, he presented a public sculpture commissioned by SculptureCenter (New York, 2019). His book ‘1996’ was published in 2020, by New York Consolidated and Inventory Press. He’s a Senior Critic in the Painting and Printmaking Department at Yale University.

mattkeegan.info