JEANNETTE MUÑOZ

LUIS BELTRAN, PHOTOGRAPHER

L’amateur ~ The amateur

The Amateur (someone who engages in painting, music, sport, science, without the spirit of mastery or competition), the Amateur renews his pleasure (amator: one who loves and loves again); he is anything but a hero (of creation, of performance); he establishes himself graciously (for nothing) in the signifier: in the immediately definitive substance of music, of painting; his praxis, usually, involves no rubato (that theft of the object for the sake of the attribute); he is—he will be perhaps—the counter-bourgeois artist. — Roland BarthesDon Luis Beltrán, my neighbor in the house across the street, was an amateur photographer. He was also a door-to-door almanac salesman, a bricklayer, a builder, and a staunch supporter of the dictator Pinochet.

Everything I know about him comes from what I remember as a child and teenager. He died in the early 90s when I started studying photography at the art school in Santiago de Chile. Don Luis had a passion that I admired: portraiture.

The street, the place where my friends and I would meet to play, was for Don Luis the setting for his photographs. He always asked us to pose in groups or individually, always in the afternoon and with the sun shining in our faces.

I cannot speak about his artistic ambitions. I don’t know how important it was for Don Luis to perfect his craft. His photographs inhabit a mysterious zone. There are more mistakes than one would ordinarily allow. There is magic in them.

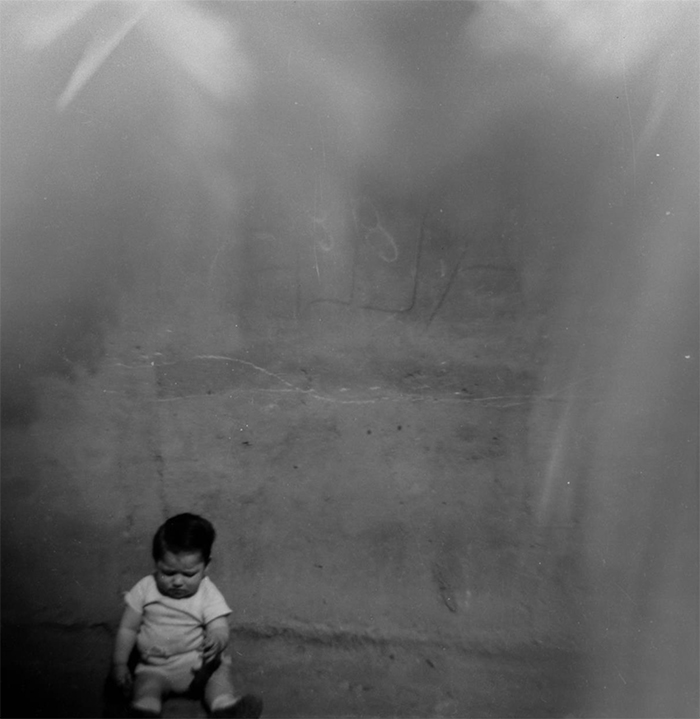

His niece asked me if I wanted his negatives, some documents and personal letters. I did. Among them there was only one photograph that he had not pasted in an album. A black-and-white portrait of a baby, framed in glass with a border of gold paper. On the back handwritten, the name Alejandro Beltrán. Possibly his son.

I do not know why Don Luis started a new life in Santiago. He was born in the South. Order prevailed in all aspects of his family life and work. I was always surprised that in spite of the dirty street, his shoes were impeccably shined. His house and front yard were also impeccably tidy; nothing was ever out of place. He made all the furniture himself in light-colored wood. The sofas had a custom-made slipcover to protect them from dust. Light came in from all sides and I loved being there. At night the blinds were always closed. I never saw artificial light through them.

Every other year my family would receive a formal invitation to their home for Christmas dinner. It was a very special occasion and highly valued by my parents.

While the adults were talking, sometimes engaging in heated political debate, I would look through the albums. They were each like a little universe that not only contained family and close friends but also neighbors and above all many children. He pasted in all of the pictures chronologically, regardless of subject. I saw myself growing up as I flipped through the pages. In some of the photos we children were unkempt and dusty, in others we were in our Sunday best. I loved finding pictures that were familiar but it was also fun to look for pictures that seemed funny to me. There were portraits where children had burst into the frame uninvited, testifying to moments of chaos in which the photographer’s patience was put to the test. Everyone wanted to be in the picture.

Within the chronological order, there was a remarkable variety of almost wild and insurrectionary visual otherness. The more I looked the more astonished I was and I would concentrate on a particular aspect, for example, the stains. I found the inclusion of these images in the album mysterious. Sometimes light had filtered in and in the color photographs there were real dramatic emulsion burns. In the black-and-white film the light leaks produced dreamlike backgrounds where the characters seemed to float in a thick fog. All the photographs were printed in 9×8 or 9×9 format, arranged side by side, and covered with the plastic typical of albums in the 1980s.

Don Luis seems to have been indifferent to the technical errors that his camera produced as long as some detail of the person or object portrayed could be recognized. One of the envelopes of developed pictures returned from the laboratory specifically states that the client requested copies of all negatives, including those ordinarily discarded.

To me, this act of reclaiming the full negative prints signifies a generous validation of the “distorted” and “defective” images. I could imagine he was disappointed or disillusioned by his early photographs and that he gradually accepted them because they were unrepeatable and unrecoverable. Don Luis was a very enthusiastic amateur photographer. A photograph that portrayed a loved one, a familiar street or some local children became a loved object that is difficult to reduce to the error or success of technique or artistic expression.

When I was studying photography, these memories intrigued me and I went to look for Don Luis’ camera. It was a plastic toy camera of very simple construction. I remember that I was quite disappointed because, in my memory, Don Luis was a proper photographer with a proper camera.

Plastic cameras built in China were cheap and users were often fully aware of their poor quality. But for someone like Don Luis it was by no means a cheap activity. The financial investment was significant: the film, the development of the negatives and the prints were a luxury that very few people in my environment could afford.

The light leakage, blur and vignetting of the plastic cameras were inherent qualities. Don Luis’ photos transcend these factory imperfections, although not intentionally, of course. In his photographs we find double exposures that are hard to believe were intentional. They must be the result of defective or erratic transport of the film. The framing is so unusual that it borders on the intrepid. Some pictures show severed heads and amputated bodies. There was a dramatic humor in those pictures and my childish eyes interpreted it humorously as well. Possibly, since Don Luis wore glasses, framing with a direct viewfinder camera may have been difficult for him.

What is remarkable to me is that these photos also find a place in his final selection. They have a value in themselves. Just like a classical statue that has lost its head or a painting cracked and blurred by the ravages of time. He included them systematically in his albums; he accepted them all with the same generosity and tolerance.

What emerges most beautifully at the intersection between various forms of non-intentionality is indebted to both maker and apparatus; the result eloquently brings to light what has always been there—the world.

All photography copyright © Don Luis Beltrán

Translation by Catherine Schelbert

—Jeannette Muñoz was born in Chile and is based in Switzerland. As a independent artist-filmmaker, she makes 16mm films since 2001 that circulate primarily in a non-fiction film context and art galleries. Her films have been exhibited in many festivals and venues including; Centro de Bellas Artes Madrid, S8 Mostra de Cinema Perisférico, l-e Tokyo Japan, New York Film Festival, Rotterdam FF Spektrum, Images Film Festival Toronto, Media City FIlm Festival Ontario Canada, Arsenal-Berlin, Ourense Film Festival, Festival Punto de Vista Pamplona, CGAI Centro Gallego de Artes da Imaxe, Xcèntric CCCB Barcelona, Palais de Glace Buenos Aires, Festival Internacional de Valdivia, Videoex Zürich, and many others.