CATARINA VASCONCELOS

THE POPPY AND THE VOLCANO

May is the month in which the flowers are stronger than the city’s concrete. The month of May always makes me believe that if we raise the city ground, we will find entire gardens beneath it.

In Portugal, May is also the month of Spike Day: the day that marks a timeless tradition related to the earth, where we pick daisies, an olive branch, spikes, rosemary and poppies. We gather them into a bouquet and place it behind the door of our house, so it will watch over us until the next year, when the bouquet should be replaced. Each component of this bunch has a meaning. The spikes, which should be an odd number, symbolize bread, the main source of sustenance. The daisy represents wealth and earthly goods. The olive branch refers to peace and light. Rosemary conveys strength and resilience. The poppy signifies life. But, for me, the poppy has always been a flower between life and death: its great beauty didn’t seem to belong to this world and its utter fragility made me think that its passage through this life was necessarily brief.

I was born in the outskirts of Lisbon, in a paradise of reinforced concrete where the flowers and weeds had to fight hard against the cement to gain the right to exist. But high up on my 12th floor we could see a mountain, the proof that nature was our only salvation. My only daily contact with nature was through my eyes, which every day peeked at the mountain from the 12th floor.

In the week of Spike Day, the fragments of nature that resisted the concrete became essential. My mother, who never cared for Catholic traditions (“Yes, Catarina, Jesus might have existed, but to say that he brought people back to life takes a leap greater than Armstrong’s on the moon!”), but who had an inexplicable relationship with all things natural, felt the need to pick that bunch in the middle of the city. From early on, my brother and I got used to my mother’s impulses, who despite not believing in God was the most ardent believer in nature. Nothing could stop her. The mountain that we could see from the 12th floor became our main pilgrimage site. It was there that we learned how to make the Spike Day bunches. Poppies were always the hardest to find. Nonetheless, we sniffed out their color and when we finally made out a sliver of red in the landscape, my brother, my mother and I ran towards it as if it were the Holy Grail. And it was. For us, the poppies had to come from the center of the Earth, from that place that is also painted red and where the gods of the underworld reign. We couldn’t have invented any of this, since for the Greeks (and my mother taught us to believe in them) the poppy was the symbol of sleep, oblivion and death. In the part of Greek mythology concerned with mystery, poppies are abundant and cover entire fields: Hypnos, the god of sleep, with wings sprouting from his head, carried poppies with him. He inherited the symbol from his mother, Nyx, the night, so frequently crowned with the red flower. Morpheus, god of dreams, capable of taking on any human shape and appear in anyone’s chimeras, walked around in eternity holding poppies. When the Romans came along they dragged the poppy from the invisible world and made it the symbol of Ceres, the goddess of plants, fields and fertility. In the Middle Ages, Christians placed the poppies inside Christ’s body and believed they saw his blood in them. In the 20th century these red flowers became the symbol of the soldiers killed during the First World War, since it is said that poppies bloomed in the fields where they died.

When we finally pulled the poppies from the earth, we knew that we had in our hands a treasure as fragile as our existence. Finding the poppies on Spike Day meant finding the element that brought the most joy to the bouquet and also its most ephemeral: from the moment we plucked the poppy we knew that it was only a matter of days before its petals started falling like silk paper and the poppy quietly returned to its invisible world.

While writing The Metamorphosis of Birds it often occurred to me that cinema, like art, lives between life and death, in an endless plunge into the center of the Earth and of ourselves. With The Metamorphosis of Birds I was lucky to spend six years working in that limbo where the poppies live: between the invisible world of our dead and the world of nature, which is full of consolation. During those six years I carried with me the passage that begins the film The Beaches of Agnès: “If we opened people up, we would find landscapes. If we opened me up, we would find beaches.”

This year, after not having done so for a long time, I went back to the mountain to gather the spike bouquet: it had rained a lot that week and the poppies had all returned to the earth. Like in the movies, when I was about to give up, convinced that the poppies had become invisible to my adult eyes, they appeared in the moment when day and night meet.

I thought:

If I were a landscape, I would like to be a poppy field.

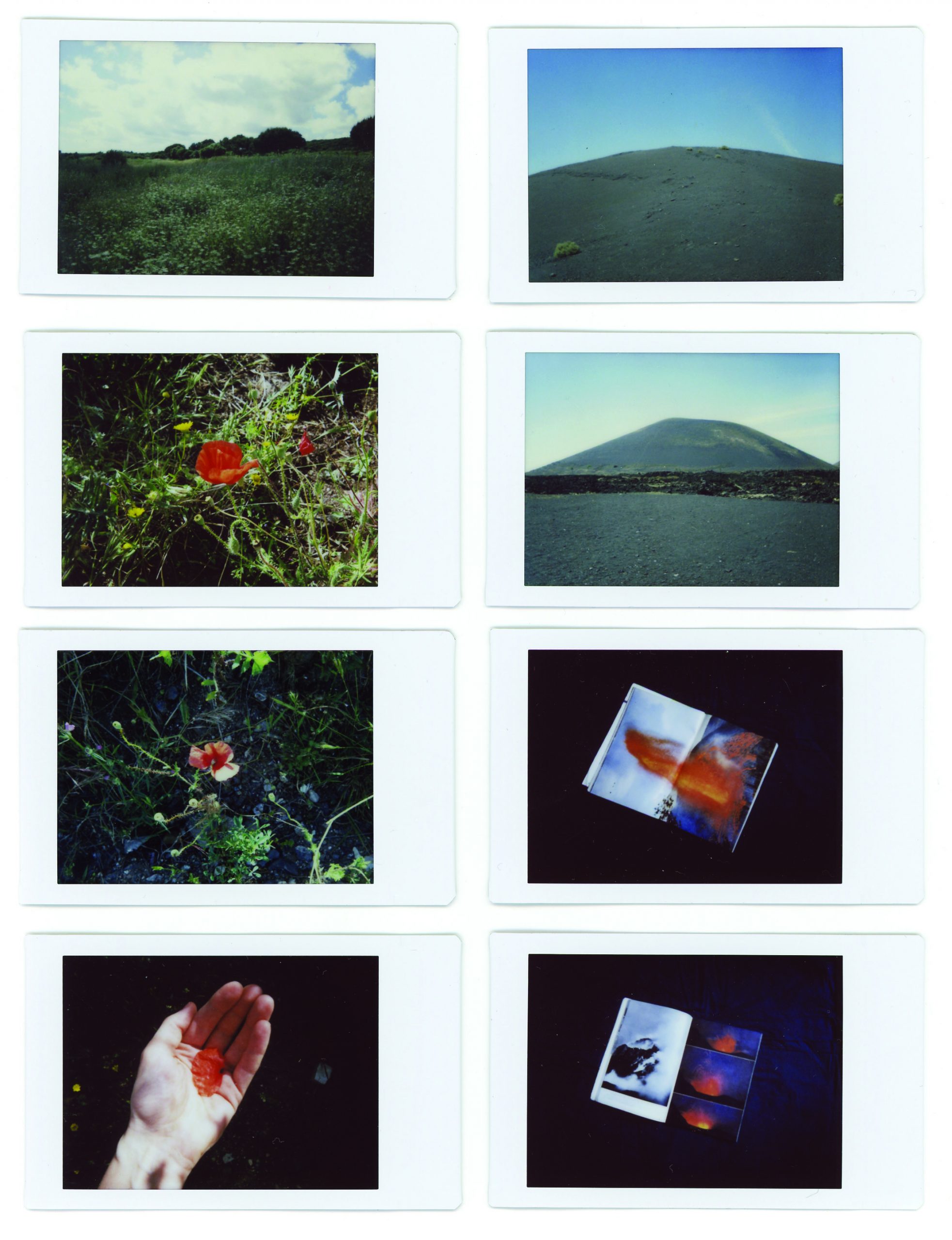

Polaroids by Catarina Vasconcelos (Lanzarote, 2021. Carnaxide, 2021)

—

Catarina Vasconcelos was born in Lisbon in 1986. She holds a B.A. from the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Lisbon and completed a post-graduate course in Visual Anthropology at the ISCTE-IUL. She received a Master’s degree from the Royal College of Art, in London, where her final project was the short film Metaphor, or Sadness Inside Out (2014). The film premiered in the Cinéma du Réel festival, where it received the award for best short film. It also screened in numerous festivals, including RIDM – Montreal International Documentary Festival (Best International Medium-Length Film Award), DokLeipzig, Moscow International Film Festival and Doclisboa. Her first documentary feature The Metamorphosis of Birds premiered in the new Encounters section at the 70th Berlinale, in February 2020, where it received the FIPRESCI award of the International Federation of Film Critics. Since then, the film has been shown in various festivals, such as New Directors/New Films or San Sebastian-Donostia International Film Festival where it was awarded best film in the Zabaltegi-Tabakalera section. The film won as well the best film award at the Vilnius Kino Festival, in Lithuania, the Special Jury Award at the Taipei Film Festival, best film award at New Horizons, Poland, among others. In this moment, Catarina Vasconcelos is preparing her first feature fiction, ‘Pintura Inacabada’ (Unfinished Painting) which is taking part of Torino Script Lab 2021.