SAMANTHA HUNT

— There’s an owl outside, 3 AM, talking to another owl. I imagine the nature of their commentary but I bet I’m wrong.

My mom lost her wedding ring again. Her house is complicated by an abundance of stuff. “I know I shouldn’t be so attached to objects,” she says, then, “Can you look in your house? Maybe I left it at your house.” She asks my dad to help her find it also. He’s dead but she finds the ring soon after, in a coin purse under a bag of hangers in the hall. “I have no idea how it got there.”

|

|

|

|

My daughters ask, “Where’s your dad?”

“He’s a cardinal.”

“A bird?”

“Yeah.”

Later one daughter explains it to a friend. “Our grandpa got the germs from smoking cigarettes. Now he’s a bird.”

It isn’t quite the lesson I intended, but it’ll do. Plus, it avoids mention of his unwashed socks and hairbrush I keep around for company, or inspiration, I guess.

The day I got engaged I stopped in the woods to pee by a pine tree. Under the boughs, someone had stashed treasure: two tiny pistols and a fake gold bracelet. The joy of the day had me temporarily, morally confused and full of myself. I stole the treasure. I’m confounded by my behavior. I hate guns. My friend Patchen was murdered with a gun at twenty-six, and when I work at my daughters’ school store I spend those mornings surrounded by five-, six-, seven-year-olds in the bright open foyer, wondering, when is the man with the gun going to arrive? When is the man with the gun going to arrive?

But I took the loot, the small pistols from under the tree. Miniatures are concentrated divinity, bouillon cubes, and there they were like an offering, a marriage present, or a tunnel back to other treasures I’d lost underneath other trees on other happy days.

My mother bought me six green lemonade glasses for my doll house. I swallowed three of them, tantalizing capsules, wanting their smallness and beauty inside. The tiny hats my grandma Norma Stallings Nolan Santangelo made for me, while similarly irresistible, made a less appetizing meal. The hats remain, the glasses only partially.

|

|

Objects are a problem. If I return the little guns now, my marriage might falter as I’m unsure of the magic they work.

Objects are a problem because they hold the dead. After my dad died I ate his half finished doughnut. I didn’t want to make a monument of his last breakfast treat, carrying an ancient piece of cake with me until it turned to dust. I know me. I have a clear vision of the jangly old woman I’ll become, wheeling my cart full of odd objects through life.

“How much for the bag of hangers, old woman?”

“They’re not for sale.”

“Well, what about that half-eaten donut?”

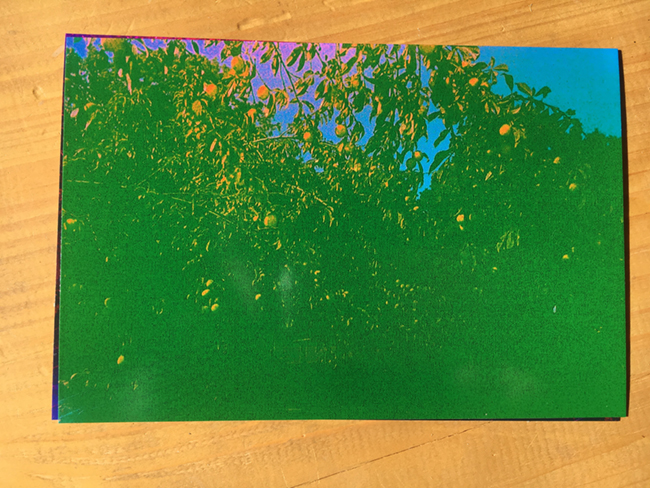

I inherited my neighbor’s end table, full-size. Both her sons were already gone: Vietnam, liver cancer, so I got a lot of her stuff. I found a disposable camera in one of the table’s drawers. When I sent the film out for processing, I won’t lie, I was hoping for a path back to the dead. Dori, Lindy, Randy. Time had really turned up the violet, blue and green in the film. Every image was of her peach tree laden with fruit.

I shouldn’t be so attached to objects either, and I’d like to return all the treasure I’ve stolen but those pistols are hard to decipher. Tiny and powerful. I don’t want to make a mistake with meaning or fortune. They grew that tree from a pit, a stone. And everyone keeps on dying, leaving stuff behind, objects I can’t get rid of because how else will the dead talk to me when birds can be so difficult to understand.

—

Samantha Hunt was born in 1971, in Pound Ridge, New York. She lives in upstate New York. Her novel about Nikola Tesla, THE INVENTION OF EVERYTHING ELSE, was a finalist for the Orange Prize and winner of the Bard Fiction Prize. Her first novel, THE SEAS, earned her selection as one of the National Book Foundation’s 5 Under 35 that year. Her novel, MR. SPLITFOOT, was an IndieNext Pick. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, McSweeney’s, Tin House, A Public Space, and many others. Her collection of short stories, THE DARK DARK, was published by FSG Originals in 2017.