RUDY WURLITZER

— Recently I have been informed that sometime in the near future I will be confronted, if that is the right word, which it probably isn’t, with the re-release of my first novel, Nog, followed in rapid order by two other novels, Flats and Quake. All three novels were written in the late nineteen sixties and early seventies, as far as I, or should I say, Nog, can remember. In the spirit of not knowing where this paragraph or contribution or possibly memories are electronically flying off to, or who it is that they might be addressed to, or why, I offer up the first paragraph of Nog. I have no traditional memory of who I was in those unhinged, free-for-all deluded days, nor, for that matter who I, or Nog, might be perceived now, although that isn’t really true and certainly not relevant. Or is it? At least I can be assured that nothing in particular and certainly nothing in general, is true inside this long-winded paragraph, a reassurance that offers a certain momentary relief. Such confusions, however deliberately perverse, allow Nog, or at least the memory of Nog, after forty or so years, to ruminate on himself, and where he might be crouched these days, burdened as he was and no doubt still is, with deliberate strategies bent on demolishing prescribed conventions of story telling, conventions which, for the most part assume that omniscient narratives are more comfortably accessible and authentic if arranged in linear progressions, insisting on a beginning, middle and satisfying conclusion, rather than allowing for a spontaneous process or non-process, one that involves Nog’s journey, a journey that consists of circular or cyclical chords that much like a manic jazz improviser exist furiously and exuberantly inside the present moment, establishing in their flow invented rhythms and unexplained shadows, illuminations that exist only to revolve endlessly around themselves. But to come back to Nog, not that Nog is or ever was away from Nog, given his engagement towards uncovering the illusions of self, or what used to be the ‘self’, as far as he can remember. In his desperation to free himself from the arrogance of omniscient reporting, Nog insists on releasing himself from what went on before, in order to free himself from what is going on now. In this way Nog defends himself from the agony of mechanical entertainment, agonies that, in his mind, always try to please and satisfy the reader, not that there are any readers, not now, or then. Nog’s promise to himself was to turn off, or delay or if not that, at least sabotage invented arrangements of words and used up insights, preferring out desperation to rely on a rush of elliptical passages arriving nowhere in particular, but still arriving, somewhere, anywhere, even if that somewhere is nowhere: a process that, along the way, embraces secret internal delights and obscure shadows; ironic surprises and humorous redundancies that seek to avoid, the literary stench of old fashioned information; information that is good, bad or indifferent, but that seeks to imprison him inside structural arrangements of time and space, which is not to say that Nog falls back on a nihilist or solipsistic view. Rather he embraces a spontaneous flux, a flux whose echoes are perfectly acceptable, given that such a flow releases egoic imprints of memory and narrative authority, imprints that depend on the illusions of memories for their location, and thus, even, perhaps, point towards false deliverance and redemption. No doubt Nog, despite his lack of ambitions, misses the usual attachments that make up recreational enjoyments and dramas, a lack which makes him attempt to corral them once again. But such attempts inevitably fail, leaving Nog even more exhausted than when he began and yet more determined than ever to push forward his attempts at inventing and re-inventing himself, In the end, or what passes for the end, he embraces his own drift, content to romp along for its own sake, and yet, despite all his efforts, coming back again and again, full circle, as it were, to himself, or what passes for himself. In this way, after all is said and done, Nog manages to breathe in and out, for his own sake, with no rewards in sight, continuing his hopeless journey to nowhere, walking and waiting at the same time, as if he has already arrived, only to find himself starting off again, towards nowhere in particular. Or so it seems.

NOG

Yesterday afternoon a girl walked by the window and stopped for sea shells. I was wrenched out of two months of calm. Nothing more than that, certainly, nothing ecstatic or even interesting, but very silent and even, as those periods have become for me. I had been breathing in and out, out and in, calmly, grateful for once to do just that, staring at the waves plopping in, successful at thinking almost nothing, handling easily the three memories I have manufactured, when that girl stooped for sea shells. There was something about her large breasts under her faded blue tee shirt, the quick way she bent down, her firm legs in their rolled-up white jeans, her thin ankles — it was her feet, actually; they seemed for a brief, painful moment to be elegant. It was that thin-boned brittle moment with her feet that did it, that touched some spot that I had forgotten to smother. The way those thin feet remained planted, yet shifting slightly in the sand as she bent down quickly for a clam shell, sent my heart thumping, my mouth dry, no exaggeration, there was something gay and insane about that tiny gesture because it had nothing to do with her.

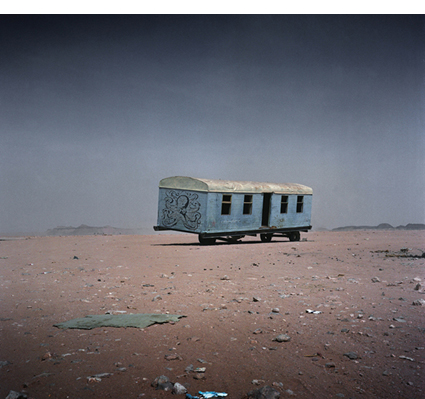

NOG, Lynn Davis, 2009

—

Rudy Wurlitzer is an American novelist and screenwriter. While he is best known for his classic screenplays TWO-LANE BLACKTOP and PAT GARRETT AND BILLY THE KID, Wurlitzer also co-directed CANDY MOUNTAIN with Robert Frank and has written over half a dozen produced films. Wurlitzer has authored five novels, including his most recent DROP EDGE OF YONDER, and one non-fiction book, HARD TRAVEL TO SACRED PLACES. His classic first novel NOG will be re-released this summer by independent New York publisher Two Dollar Radio, followed in short order by two other early novels, FLATS and QUAKE.