PETER TSCHERKASSKY

THE TOM GUNNING, OR: HOW THE COCK GOT ITS TAIL

— A few weeks ago I received an e-mail from my dear friend Nicole Brenez asking me to write a “Love Letter to (one of) your favorite artist(s)” on the following occasion: “The wonderful online film journal, La Furia Umana, edited by Toni d’Angela, is preparing its first printed issue: In a nice turn-around of things, the best of the internet will become a physical publication. This first, special issue will open with a series of letters from filmmakers: each is invited to write about a favorite artist, freely chosen from the past, the present, or even the future… from any field, but above all, of course, from film.” Well, in response I wrote a letter to Pat O’Neill, who probably had the biggest influence on my own filmic aesthetics (as I have pointed out in several interviews throughout my career.)

Anyway, if I had been asked to write a similar letter to “one of your favorite film theoreticians,” I would have undoubtedly chosen Tom Gunning. By now I have known Tom for almost twenty years and I have had the honor of inviting him to two symposia I organized in Vienna: The Modernist Vision in 1996, and Early Cinema and the Avant-Garde in 2002.

During preparations for The Modernist Vision I went with a friend of mine, (then) film journalist Claus Philipp, to a cocktail bar to discuss how things around the symposia had evolved. When the waiter came to take our orders Claus was so absorbed by our topic that he didn’t ask for his favorite cocktail, a “Tom Collins,” but ordered a “Tom Gunning.” Instead of reacting bewildered, the waiter simply turned around and left (appearing a few minutes later with a perfectly mixed “Tom Collins”). I myself took this wonderful incident as an inducement to commence a kind of structural/linguistic investigation as to what a cocktail called “Tom Gunning” is made out of – not least because I wanted to present the drink to Tom as soon as he arrived in Vienna. I sent the result of my research as a letter to Tom in advance of his visit:

Dear Tom,

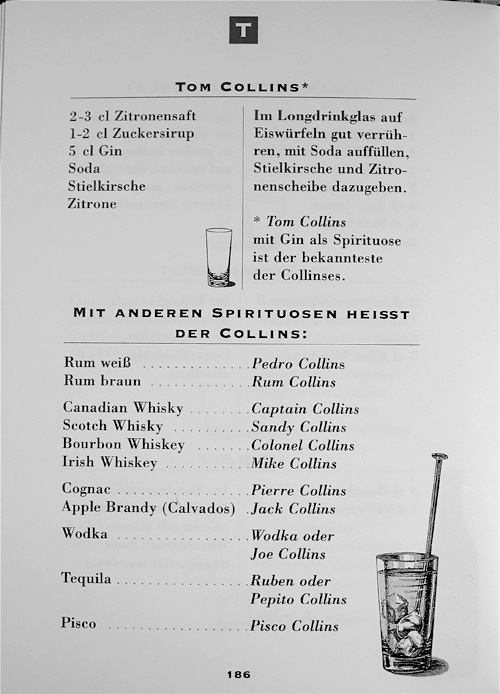

Finally – after long and intensive investigations I found out what a TOM GUNNING is made out of. The following results of my research are based on the TOM COLLINS as definded by Charles Schumann in his book American Bar. The Artistry of Mixing Drinks (1991). Despite his first name Mr. Schumann is a German, a former boxer and one of the great authorities on mixing drinks. He resides in Munich where he runs his famous bar Schumann’s. For many passionate drinkers he’s simply the best.As you can tell from the enclosed photocopy, a TOM COLLINS consists of gin, fresh lemon juice, liquid sugar (sugar syrup or “treacle” or “molasses”, as my dictionary suggests), combined with soda (in German “soda” always means “soda water”), decorated with a cherry and a slice of lemon. If you change the basic liquor, the first name of the COLLINS changes: with white rum it becomes a PEDRO COLLINS, with cognac a PIERRE COLLINS, and so on.Now let’s compare TOM COLLINS and TOM GUNNING. Since both of them are Toms, we easily can tell that TOM GUNNING’S basic liquor is Gin. A quick solution to an important question. But things get more difficult as we approach the surname. There are some remarkable and very instructive structural similarities between the two names which suggest splitting the names as follows:

CO/LLIN/S – GU/NNIN/G

Remember – a COLLINS contains lemon juice – and if we investigate the “CO” we discover that it recalls the citron! GUNNING starts with GU; so if we look for a fruit with a G as its first letter and consisting of two syllables (like the citron), we discover not only the grapefruit but also that the third letter of the second syllable is a u – just as the o in ci/tron:

C O/LLIN/S – G U/NNIN/G

ci/tron – grape/fruit

1 3 – 1 3

And this was step Nº 2!

Next step.What significantly differs are the very last letters of the two names: S and G. Well, the TOM COLLINS gets filled with soda water – and of course the S is the signifier for soda. Since the S vanishes, there must be another modifier for the TOM GUNNING – something with a G. My very first thoughts directed me to Grenadine syrup, but that differs much too much from soda – totally unsatisfying. And then I had the idea of ginger ale! Even so, in the beginning I was not really convinced though I was quite sure that this could very well be the solution… and I went on to solve the riddle of /LLIN/ and /NNIN/.These two little beasts really gave me a hard time, especially since they resemble one another so much. I was sure that within /LLIN/ must be the sugar of the COLLINS. I thought if /LLIN/ stands for treacle the /NNIN/ might be powdered (confectioners’) sugar. But I was absolutely convinced that He, who is behind all of this, positively couldn’t want us to pour more sugar into the TOM GUNNING than the ginger ale already contains! Well, the solution came when I found out that the N alone simply stands for sugar!N = sugar! (Seemingly simple things always hold the greatest difficulties in life, don’t they?) And of course /(L)LIN/ means liquid sugar. So instead of dividing GUNNING like GU/NNIN/G we have to read it as GU/NNI/NG – with the /NG/ for “zuckriges Ginger Ale” – which translates as: sugary ginger ale!And what’s more: the German word for ginger is “Ingwer”. And if we read GUNNING as GU/NN/ING, we have the INGwer as well – the very last proof that ginger ale must replace the soda.But now the mysterious /NN/ still has to be decoded. We see that there is no deeper meaning to the first L in COLLINS (besides making it very liquid) which allows us to dismiss the first N in GUNNING. And we have to stick to the version of GU/(N)NI/NG to find the hidden meaning of the /NI/. It’s in the center of the whole thing, tiny and important as a heart. It has to harmonize, has to support the flavor of the other elements. As it is in opposition to the /LI/(quid sugar), it must be something bitter – and which of those three magic bottles, Grenadine, Orange Bitter and Angostura – flavoring parts of so many great cocktails – could it be? Right. It’s OraNge BItter!Here we are. Dear Tom, I’m proud that I was able to reveal that the TOM GUNNING consists of gin (and I would strongly recommend the dryest of all – Tanqueray), grapefruit juice, Orange Bitter and ginger ale. The open question as to the exact amount of each component is proof that this drink is a freshly discovered classic within the wonderful world of cocktails and the answer has to be found out during many nights of excessive studies with lots of different versions of TOM GUNNING.*)(Peter Tscherkassky, 1996)

*) And we did find out: It’s 5 cl Gin, 6 cl grapefruit juice, 5 cl ginger ale, and some dashes of Orange Bitter.

Okay. So much for what you can taste as my obeisance towards Tom. And now comes what you can see. In 2010, nearly fifteen years after the discovery of the “Tom Gunning,” I made a film called Coming Attractions – strictly hand-made in my darkroom. Coming Attractions and the construction of its images are woven around the idea that there is a deep, underlying relationship between early cinema and avant-garde film. Tom Gunning was among the first to describe and investigate this notion in a systematic and methodical manner, in his well known and often quoted essay “An Unseen Energy Swallows Space: The Space in Early Film and Its Relation to American Avant-Garde Film” (in: John L. Fell [ed.], Film Before Griffith, Berkeley 1983).

Coming Attractions additionally addresses Gunning’s concept of a “Cinema of Attractions.” This term is used to describe a completely different relation between actor, camera and audience to be found in early cinema in general, as compared to the “modern cinema” which developed after 1910, gradually leading to the narrative technique of D.W. Griffith. The notion of a “Cinema of Attractions” touches upon the exhibitionistic character of early film, the undaunted show and tell of its creative possibilities, and its direct addressing of the audience.

At some point it occured to me that another residue of the cinema of attractions lies within the genre of advertising: Here we also often encounter a uniquely direct relation between actor, camera and audience. The impetus for Coming Attractions was to bring the three together: commercials, early cinema, and avant-garde film.

Coming Attractions is divided into eleven individually titled chapters, all eleven related to either a famous early film (by Auguste & Louis Lumière, Georges Méliès, Birt Acres & Robert W. Paul, Henri Chomette, Fernand Léger and Jean Cocteau), or to an influential publication on the field.

Chapter #1, “Cinema of Attraction”, attempts a literal re-interpretation of a cinema of attractions. Chapter #2, “Cubist Cinema №1: An Unseen Energy Swallows Face” of course refers to Tom Gunning’s above mentioned essay “An Unseen Energy Swallows Space.” Here it is, with its soundtrack by Dirk Schaefer:

And here is Chapter #6: “Cubbhist Cinema №3: The Path is the Goal (Natura morta with Tulips, Guitar, Pork Roast and My Wife in the Bush of Hosts).” The chapter title refers to Standish D. Lawder’s influential book, The Cubist Cinema (New York 1975). Meanwhile it also represents a playful allusion to the Buddhist saying that the path is the goal. It is based on a commercial for stockings. We see a woman running across a meadow over and over again, seemingly without a goal she could ever attain. The imagery makes use of common motifs in Cubist paintings (mainly Braque and Picasso), and playfully refers to that wonderful record by Brian Eno and David Byrne, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (1981) – using a lot of found footage in the form of radio preachers. I inserted woven fabric into the meadow (in early cinema dream sequences sometimes were filmed through tissue), some Brakhage-Mothlight bushes, some coffee party hosts, some Natura morta – “dead nature” in the form of cooked food – and I got my lady running.

—

Peter Tscherkassky, born in Vienna in 1958, started making films in 1979. Today he is acclaimed as one of the most significant artists in the field of avant-garde filmmaking. His films have been honored with more than 50 awards including the Golden Gate Award (San Francisco), Main Prize at Oberhausen, and Best Short Film at the Venice Film Festival. Tscherkassky earned his Phd. in philosophy in 1986 with a dissertation entitled FILM AS ART and started teaching in 1988. He has organized several film festivals and curated countless film programs. Since 1984 he has published numerous essays on avant-arde film and in 1995 co-edited the book PETER KUBELKA with Gabriele Jutz. in 1991 he co-founded sixpackfilm. In 2005 INSTRUCTIONS FOR A LIGHT AND SOUND MACHINE was premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and a bilingual (English/German) monograph entitled PETER TSCHERKASSKY was published. His light box installations have been exhibited throughout the world, including a one-person show at the renowned Gallery naechst St. Stephan/Rosemarie Schwarzwaelder. 2008: Lecture and world premiere of the original 35mm version of PARALLEL SPACE: INTER-VIEW at the Louvre in Paris. 2010: World premiere of COMING ATTRACTIONS at the 67th Mostra internazionale d’arte cinematografica di Venezia (Premio Orizzonti Cortometraggio). 2012: Publication of the book FROM A DARK ROOM. THE MANUFRACTURED CINEMA OF PETER TSCHERKASSKY (English/Spanish; Mexico City: Interior 13, Alumnos 47). Editor of the book FILM UNFRAMED: A HISTORY OF AUSTRIAN AVANT-GARDE CINEMA (Vienna 2012). In the 2012 ranking of the Greatest Films of All Time, published every ten years by the BFI film magazine Sight & Sound, OUTER SPACE was honored with the ranking of position #322 (Filmmakers poll) and position #377 (Critics poll), based on 846 top-ten lists of cinephiles including directors, academics, distributors, curators and writers from 73 countries who collectively cited 2,045 different films. INSTRUCTIONS FOR A LIGHT AND SOUND MACHINE was honored with the ranking of position #894 (Critics poll).