PETER HUTTON

THE LANDSCAPE OF BERLIN 1980

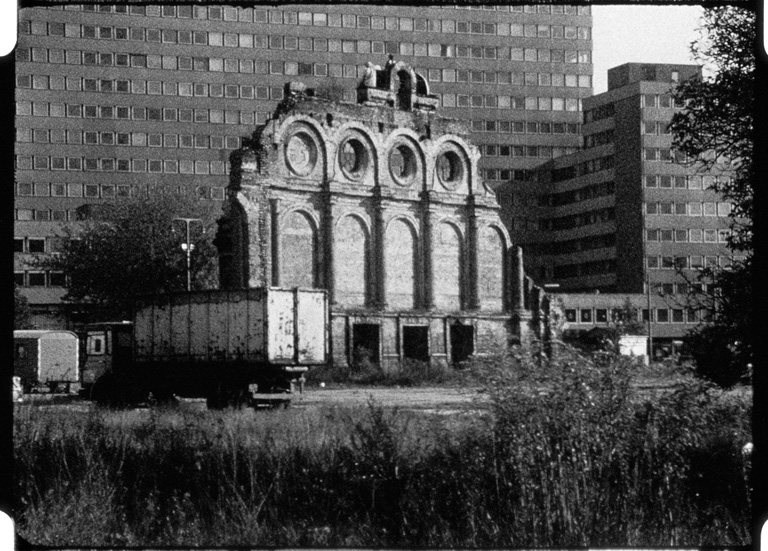

— In 1980 I spent a year in living in West Berlin as a guest of the DAAD (Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst). They provided me with an apartment, a stipendium and the resources to complete a silent film study of Berlin. It was dreamlike. I’d never been treated so well. I told people it felt like I had won a Nobel Prize. I was initially situated in Wannsee, a bucolic suburban section outside of the city where many rich German industrialists lived during WWII. Far from the city center, Wannsee, with its trees, lakes and spacious homes, was in stark contrast to my image of Berlin, an image based on Walter Ruttman’s film Berlin Symphonie der Großstadt. Two weeks later I moved to an apartment near Berlin Mitte and began wandering around with my Bolex. The Berlin of 1980 was steeped in the atmosphere of a John la Carré novel. The cold war was on. Reagan had just been elected president in the US. The city I saw felt more like Ruttman’s Berlin after a lobotomy: vacant lots, ugly modern architecture, a lot of negative space. It was also in color, albeit a brownish gray. Clouds of coal ash would drift over the wall from the east on certain nights, adding a sulfuric patina to the atmosphere. I spent a considerable amount of time wandering around an area between Kreuzberg and the Tiergarten. The landscape was more rural than urban. There were a great many open spaces, no man’s land evoking scenes from Ozu’s, I was Born…. But, where the boys played baseball in the fields between the city and the country. There were modern structures here and there, but I was attracted to the abandoned quality of the landscape. I rarely met people when I was shooting, but when I did, I filmed from a distance. Almost everything I filmed at this time was either damaged architecture or a broken landscape that was reminiscent of another time (the 1920s or the 1950s). A feeling of alienation pervaded this area. In retrospect, I realized that I was attempting to construct in film a scale model of the city as it existed in a time period shortly after the end of the war, about the same time my knowledge of German history stopped. I was drawn to one particular area in Kreuzberg: an overgrown field behind the Anhalter Bahnhof. A chunk of the original façade of the train station remained standing, like a piece of brown bread that had been partially eaten by rodents. Behind the façade was a vast field, crisscrossed with many worn paths, where trucks occasionally parked. Beyond the field were old industrial structures, including a bunker, originally part of the railroad yards, now collapsed and overgrown with trees and bushes. The area was both mysterious and foreboding. This was my favorite piece of landscape, and I returned to it many times throughout the year. The site became popular with punks who used it as a kind of nihilistic playground. German punks were scary.

One day I was quietly filming a configuration of plants that had grown through a broken window in one of the crushed buildings. Someone had given me some hashish, which I had been smoking. I became transfixed by the quality of light in the shattered window, which evoked an image from Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast. Suddenly a tiny woman jumped out of the bushes. I just about had a heart attack! “Mein Gott!” I said. “Was machts du?” “Und Sie?” she responded. “I’m looking for history,” I said. My German was terrible. Realizing I was not a native speaker, the woman answered in English: “I’m a botanist and I’m collecting plants.” I was a bit stunned. I wanted to make a portrait of her, but I didn’t want to make her uncomfortable. She went on to explain that in this particular area of Berlin there were more species of plants than anywhere else in Europe. “Why is that?” I asked, still not sure if I was talking to a real person or a hallucination. She explained that trains came to Berlin from across Europe, carrying on their surfaces hundreds of seeds and spores. Upon arriving in Berlin the trains were washed. The seeds then germinated, and many species of plants that had not been indigenous to Berlin began to grow. Because the train station was almost completely destroyed during the war and had remained virtually untouched for 40 years, the plants continued to proliferate. ”This is my laboratory,” she said, surveying the ruins. I was dumbfounded and feeling a bit uneasy. I thanked her, picked up my camera and wandered off. The woman disappeared into the bushes.

I’m currently editing the footage I shot 30 years ago, and I still wonder if the little woman was real. The larger question is why it has taken me 30 years to finish this film. I think Berlin was a “work in progress” in 1980. The wall was a point of immense psychological fascination—a symbol of what was beyond, further to the east. West Berlin was culturally familiar to me despite being foreign. I made several trips to the USSR via East Berlin during this time and shot footage in Moscow and Leningrad. In the years following my Berlin adventure I made films in Hungary (Memories of a City) and Poland (Lodz Symphony). The cold war was for me a time of forbidden pleasures, a time to wander across a landscape frozen in another era and fraught with abstract danger. It was exciting and mysterious. I became a peripatetic spy stealing dead history with my Bolex. In the Eastern Bloc countries I traveled to and filmed, I was frequently stopped by police and questioned. This never happened in West Berlin, despite all the anarchy of the 1980’s and the feeling of living in a police state. I was, however, occasionally stopped from filming by radicals who thought I was the police. This was really weird.

Recently I discovered Google Earth and went to Berlin on my computer. It was amazing how tiny and alien the landscape was from outer space (I’ll never find that woman now), and how little I could recognize from the city I knew in 1980.

Peter Hutton was born in 1944, in Detroit. He is one of cinema’s most ardent and poetic portraitists of city and landscape. A former merchant seaman, he has spent nearly forty years voyaging around the world, often by cargo ship, to create sublimely meditative, luminously photographed, and intimately diaristic studies of place, from the Yangtze River to the Polish industrial city of Lodz, and from northern Iceland to a ship graveyard on the Bangladeshi shore.