MICHAEL BROPHY

I get most of my ideas and images from driving to and fro in the Pacific Northwest and walking up and down in it. Scouting out landscapes and our often fraught relations with the land. I’m interested in the landscape not merely as a backdrop, or scenery, but rather as a character with agency. So these pictures of mine are really a form of landscape portraiture.

I trace this interest back to my childhood on the edges of Forest Park in NW Portland, the largest park within a city’s limits in the US. The Wildwood Trail runs more than 20 miles along the Tualatin ridge. When I was a kid the ridge extended, forested, to the coast range, and a black bear had to be tranquilized in a neighbor’s backyard. Development severed this link, but coyotes are regular visitors.

I used to terrify my mother because I would play behind the houses where the yards met the forest, rather than out front. Playing games like moving around the neighborhood without touching concrete. Like in Opal Whitely’s journal, I remember going on these “explores” from a really early age. Always alone, and this capacity for solitude turned out to be really useful for a painter.

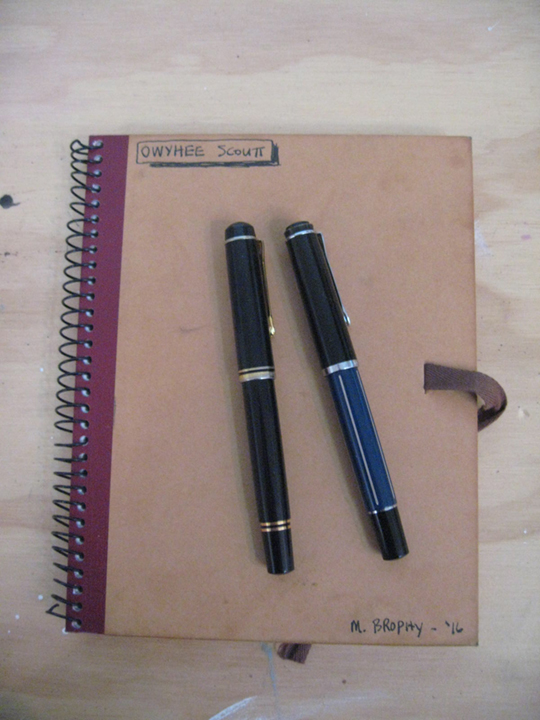

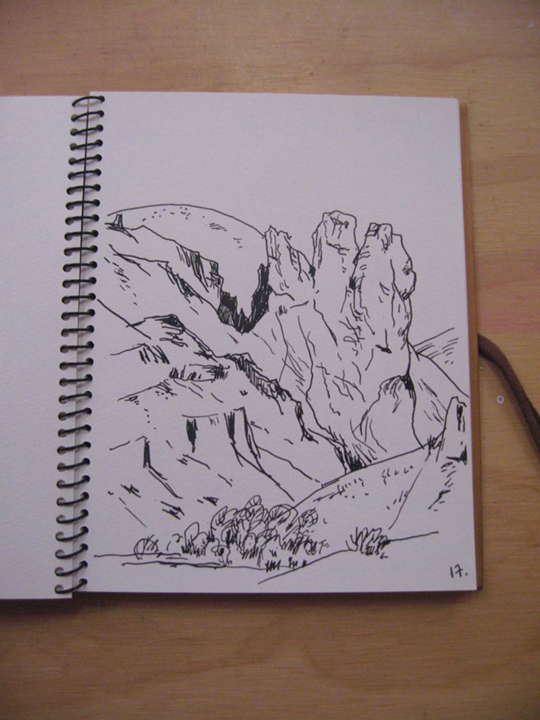

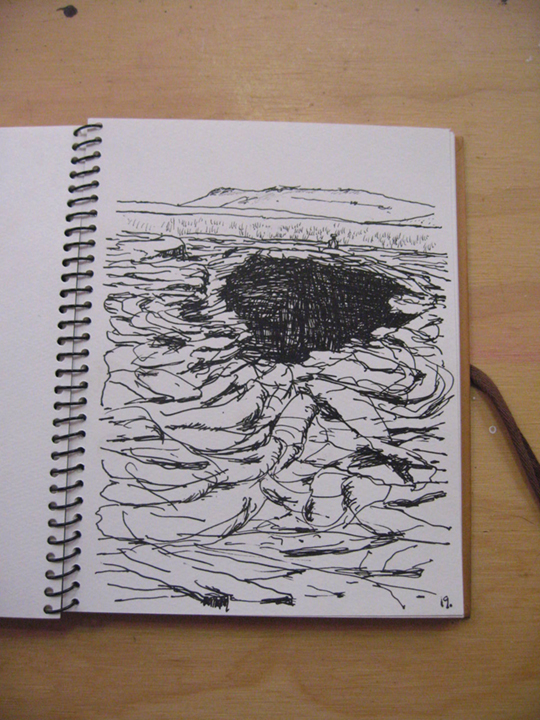

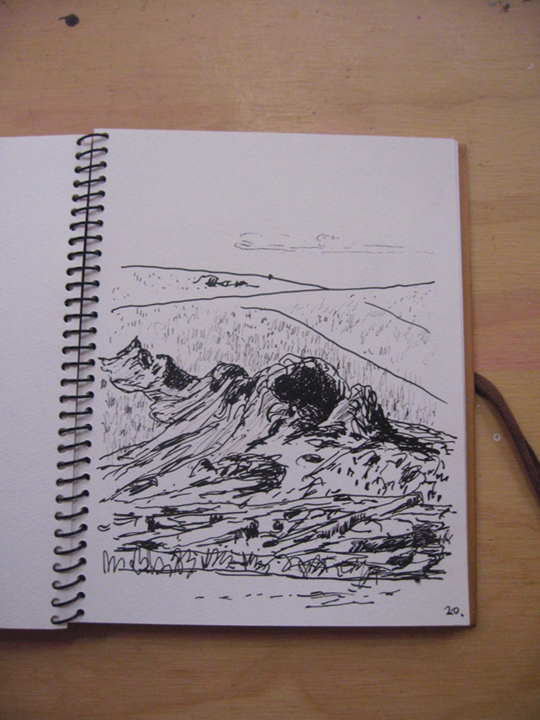

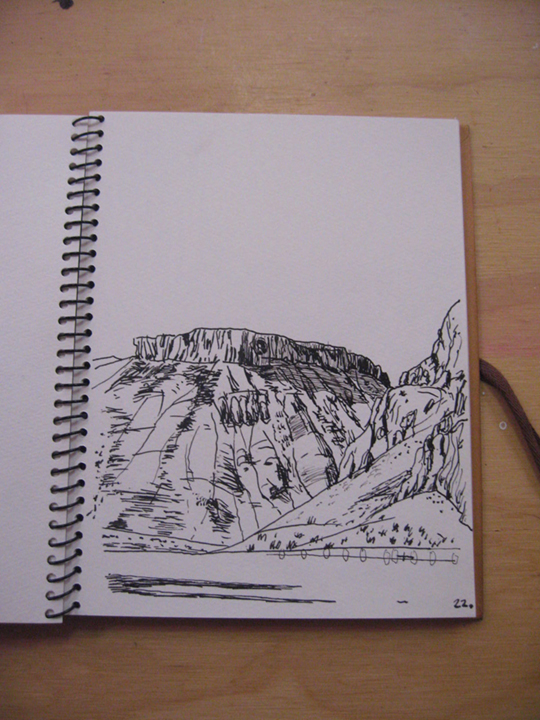

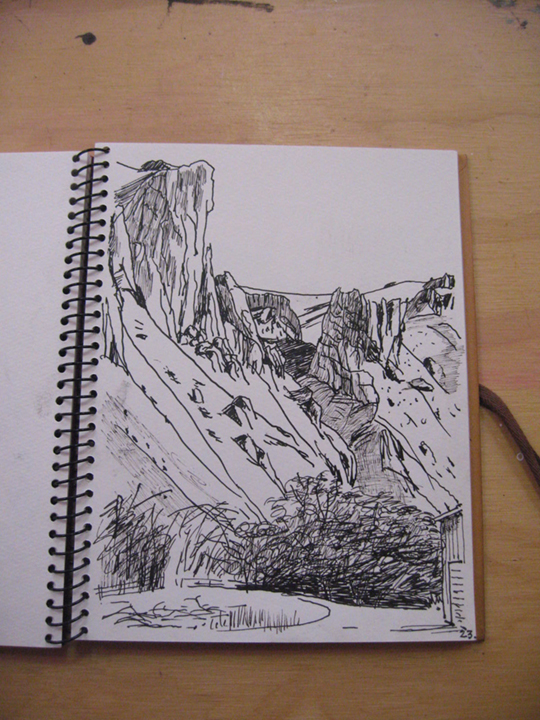

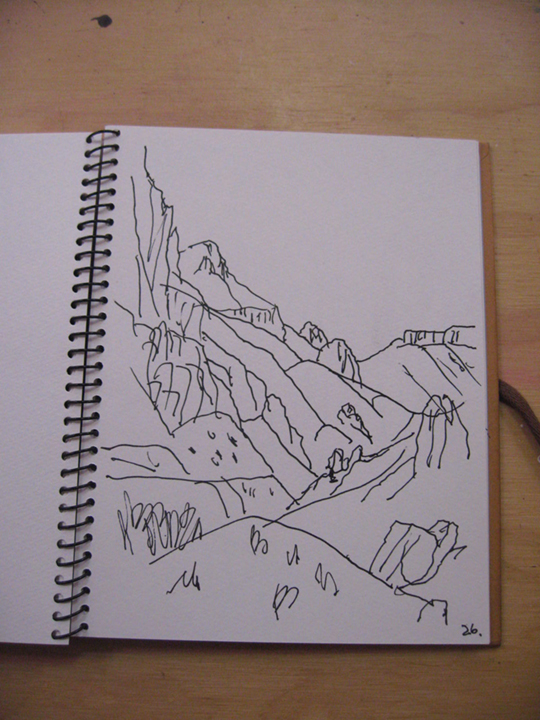

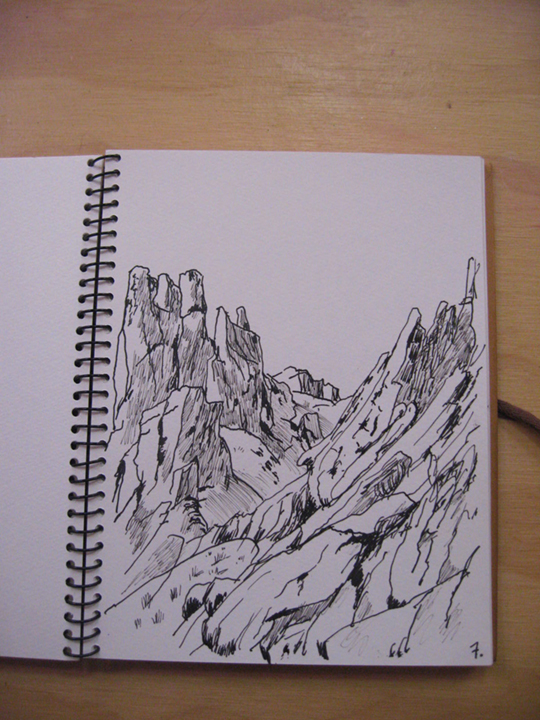

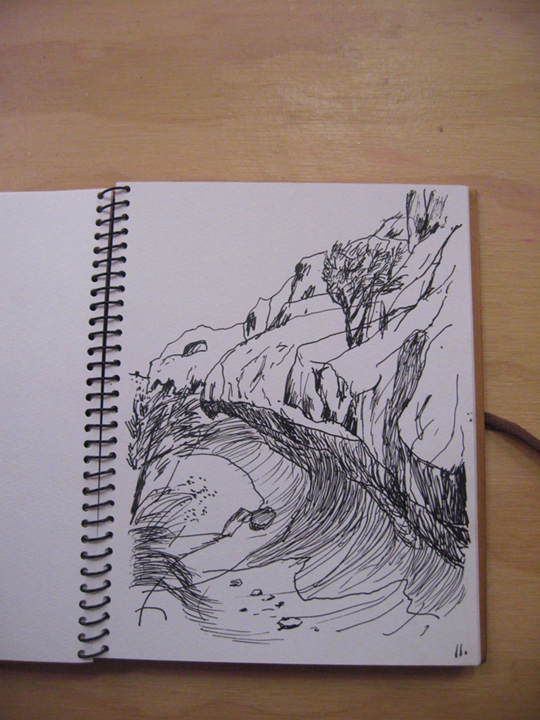

When I go out on these scouts I bring along my kit. Inside a small Filson shoulder bag are sketchbooks, fountain pens, ink, and a camera. I’ve always drawn with fountain pens, and I’ve had the black one for 25 years and the blue barreled one for about 20 years. The first pen I had, a beautiful reproduction of a 1930s pen, bought while still in art school, I lost somewhere. The loss still pains me.

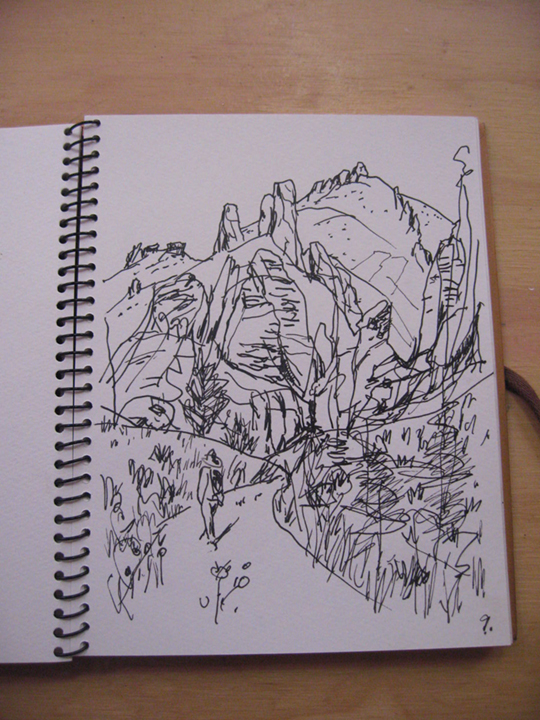

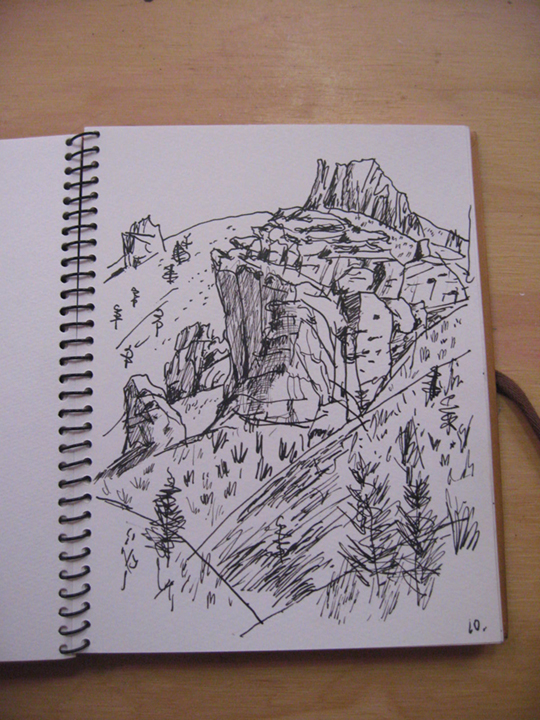

I like the finality of the ink, putting a line down and having to react to, with, or against it. No erasures, just barreling forward. You really see something when you’re drawing it. The camera, now digital, is small and simple. The drawings and photos, though essential, are the raw source material for my paintings, and all the paintings are studio productions.

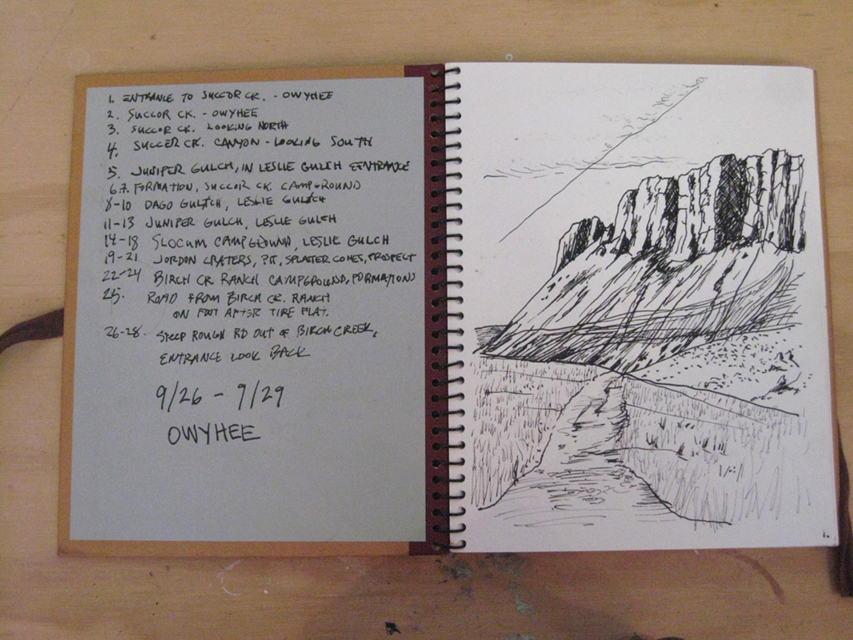

The most recent scout was a trip to the Owyhee, at the end of September. The Owyhee, an archaic spelling of Hawaii, is so named because a pair of Hawaiian fur trappers disappeared in this country in the 19th century. It’s located in the far SE corner of Oregon and is stark high desert, and very remote. A land of towering rhyolite formations, honeycombs, lava flows, basalt, bone-dry yellow grass, sage, a sky so blue as to seem almost black, starry nights, and the Milky Way’s strip from horizon to horizon. Strangely, we didn’t see the moon the entire trip; only a handful of people, cows, and gravel roads.

All the places are named after calamities, disasters, and misfortunes. In fact, the whole county is name Malheur, after the French for “bad time,” “bad luck,” etc.

The first night we camped at Succor Creek (pronounced “sucker”) under the trees that hug the bank. Then on to Leslie Gulch, named for Hiram Leslie, a 19th-century pioneer who was struck and killed by lightning here. The gulch is known for its rhyolite formations of ochre, red, purple, and corpse green. In the morning we were buzzed by two F-16 fighter jets, deafeningly loud and so low as to clearly make out their undercarriages as they banked hard right above us, then were gone.

On to Jordan Craters, a 28-square-mile lava flow from eruptions 3,000 to 9,000 years ago, which in geological time is now. This is a pahoehoe flow, ropey, with splatter cones, enormous pits, precarious footing, and sharp surfaces. During the height of summer, temperatures reach 120° F. A terrifying place and so quiet as to hear the earth’s hum.

Finally, on to Birch Creek Ranch. Thirty miles of gravel road to the entrance of the Ranch road, where a sign warned: “Extremely steep and rough road, extremely slippery when wet, high clearance vehicles recommended.” The road was a single-track dirt and boulder-strewn six-mile nightmare to the river. We crossed four creeks at the bottom, and traveled the six miles in one and a half hours, one way. At the bottom were the ruins of the original pioneer structures and a contemporary house set amongst trees with sprinklers going. We traveled another mile to the large, open, recently harvested alfalfa field between the Owyhee River and rhyolite cliffs, and set up our final camp. A peculiarly warm wind blew through the night (the other nights were very cold) and we awoke early on high alert, worried that rain was coming, making the road back up impassable.

Then we faced our own small calamity, a flat tire. And what turned out to be an ill-fitting tire iron, with no way to reach the recessed lug nuts of the wheel. We hiked to the house with the sprinklers, hoping someone was there with tools. A pickup was out front, empty, with the engine idling, and onto the porch stepped Jim, a BLM employee who lives year round in this isolated spot and who had a wrench that fit. He told us that last winter he went five weeks without seeing another human being, the road being impassable. We were struck by how isolated we were—only three people in a hundred square miles.

One and a half hours on dirt, two hours on gravel, and we were back on concrete for the eight-hour drive back to Portland.

The Owyhee is being considered for National Monument designation. The road signs were ubiquitous: NO MONUMENT.

Owyhee Scout 9.26–9.30, 2016

Miles traveled 1,150

Animals sighted:

Bats, bighorn sheep, chukars, cows, coyotes, flickers, hawks, ground squirrels, many flying insects (flies, gnats, etc.), mule deer, lizards, ravens. No rattlesnakes.

—

Michael Brophy was born in Portland, Oregon, in 1960. For over two decades Brophy has painted the Pacific Northwest landscape. He has shown extensively in the Northwest in both solo and group exhibitions.