LUCY SANTE

MY TWENTIETH

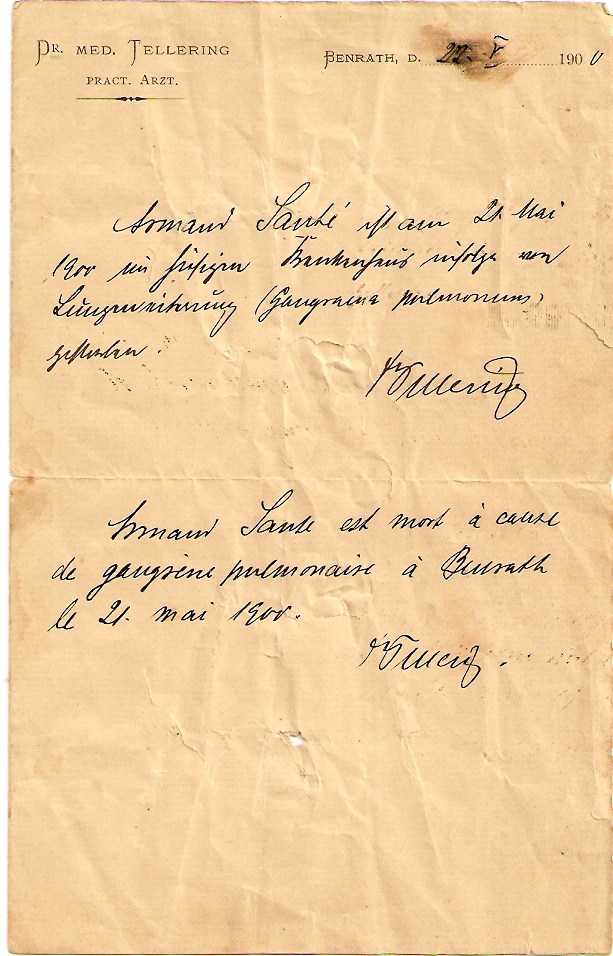

1900. My great-grandfather Armand Sante dies, age 49, of pulmonary gangrene, whatever that entails. How he, an illiterate day laborer from southeastern Belgium, came to die in a suburb of Düsseldorf is something I will probably never know.

1910, approximately. My maternal grandfather, Édouard Nandrin, a country boy from the tiny village of Odeigne, is sowing his wild oats in the big city, in this case Liège, where he is employed for a while as a streetcar conductor and inhabits the role with military bearing. It gives him probably the greatest authority he will enjoy in his life.

1920, or actually 1921. My father is born, the one and only postwar issue of his parents, who are by then aged 42 and 33. His father works in the textile mills while his mother stays at home to look after the infant and his older sister, Armande, who is 8. They live in Verviers, in a tenement near the river, in a neighborhood that has been home to the family for centuries.

1930 or so. My mother’s family, tenant farmers from the Ardennes, undertake the hejira to the city in the face of the worldwide economic collapse. My mother is here shown outside their farmhouse, charged with entertaining rusticating city-dwellers who have stopped on their walk for a glass of milk. Very soon she will be living in a tenement flat, surrounded by textile mills.

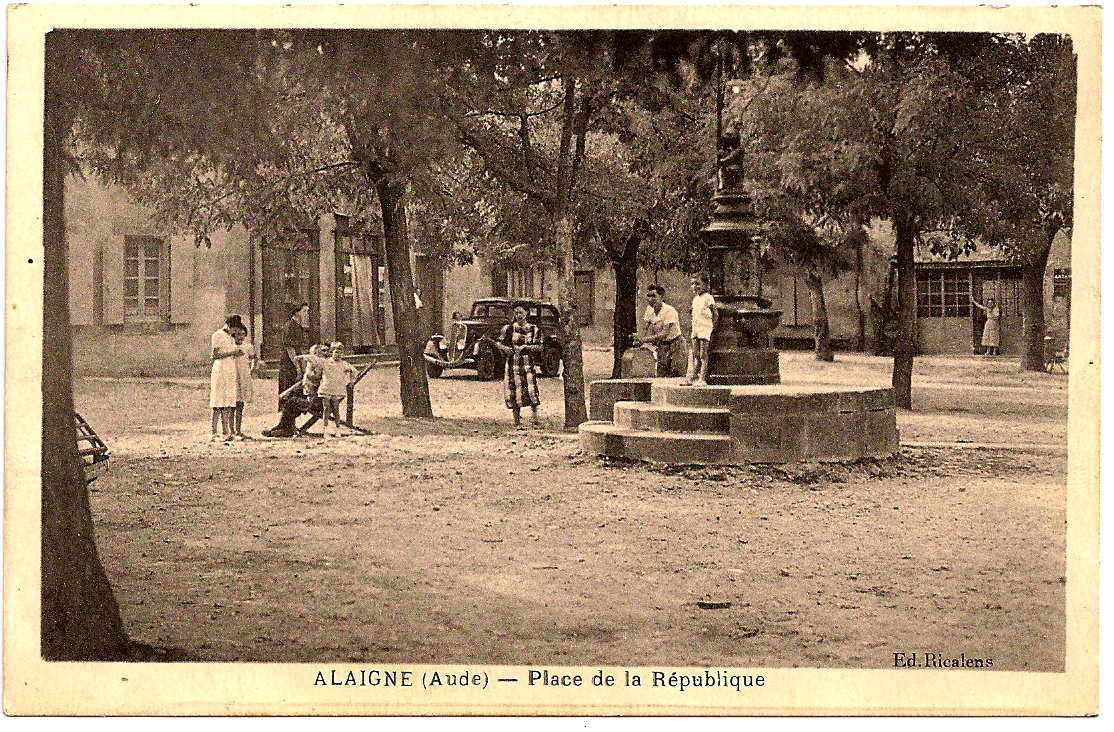

1940. My mother’s family flees the approach of the German army, for whom Verviers is the first stop in Belgium. By bicycle, foot, and train they will eventually reach Alaigne, in the foothills of the Pyrenées. They will stay for a few months, eating primarily rabbits trapped by my grandfather, until Belgium calls back all the exiles in 1941. My father spends the war in disguise, avoiding being sent to a labor camp in Germany.

1950. My parents marry, in February and wearing dark postwar colors. My father’s prospects are good–he is bright and energetic–although he is largely uneducated, having left school at 14, and he will always stand just a few steps down from the landing on the stairway of success. My mother, who stayed in school until she was 16, works as a secretary in the state family welfare agency. After a few tragically unsuccessful attempts at bringing forth progeny they will finally succeed with me four years later.

1960, or the very end of 1959. My father and I stand by the S. S. Tervaete, the Belgian freighter that will take us on our de-emigration journey from New York to Rotterdam. My parents and I had arrived in the United States the previous February, but they didn’t like the place. Because of various familial tensions, however, we will return to America within six months. My parents will attempt to return to Belgium three more times, the last when they have retired from their jobs, but they will die in New Jersey.

1970. I am in high school in New York City, to which I commute by train and subway two hours each way every day from the New Jersey suburbs. Here I am at an antiwar rally in Central Park (that’s me with the peace button on my shirt). I have arrived at what I think of as the summit of the world. Everything is within my reach in New York, and the intoxication of it is such that I will be expelled from that high school before the end of the year.

1980. The framing and focus of the photograph reflect the circumstances. I am out at night–here at Tier 3, on West Broadway and White Street–and I probably have ingested a complex pharmacopeia of substances. This is what I do most nights. I get by on minimum-wage jobs, intend to become a writer without doing anything much about it, and live most fully within the music that surrounds me.

1990 or actually the last months of 1989. I am receiving an award, wearing a suit, impersonating an adult, with assistance from the male-pattern baldness that has afflicted me in waves since age 17. I am actually a writer by now, with clips to show for it and soon enough a first book. The money that accompanies the award is the first significant sum that I have ever seen. For better or worse I am now charged with an additional load of responsibility.

2000, or to be more precise September 11, 1999. My son, Raphael, is born in Cooperstown, New York, the first and to date only Sante ever to be born outside an eight-block area in Verviers, Belgium. I am a terrified and psychologically unprepared father, and I am just grasping that people are born with personalities. Raphael as an infant is no more a blank slate than I am. His theatrical inclinations and I could almost say his sense of humor are apparent almost the instant he exits the womb.

—

Luc Sante’s books include LOW LIFE, EVIDENCE, THE FACTORY OF FACTS, KILL ALL YOUR DARLINGS, and, most recently, FOLK PHOTOGRAPHY. She teaches writing and the history of photography at Bard College.