JAKE SKEETS

MAPPING THE FIELD FROM THE CAMERA ROLL

There is something about living in the place where your family has lived for thousands of years. I feel like there is a misbelief that because I am from these lands that I should know how to navigate them with ease. The precursor to that misbelief is the navigation of land, the way around it, the way through it, the way you maneuver within it, the breaking of the land to the organizational structures of the human mind. In the phrase, “I know this place like the back of my hand,” the land becomes synonymous with a part of the body, something that is known, familiar, something with utility like the hand, something always seen like the back of it. In fact, the ancestral homelands of my community and people remains largely a mystery to me. Each trip through Dinétah becomes one of discovery, journey, roaming (quite literally because of cell service), and exploration. There is an unconscious mapping that happens within the mind, one that aims to look for the familiar within the landscape, to position oneself in relation to other things. This happens perhaps for convenience. Perhaps mapping happens because one wants to conquer the land, to break it. After all, the first step to breaking a wild horse is the roping. What is a map if not a lasso? So in thinking through the things that influence me, I kept returning to the land. The various adventures in and the way I mapped the places not with conquest in mind but with language and image in mind. We map things but it is up to us to map things for the right reasons. The landscape is mapped best when it is mapped with memory and story. Scrolling through my iPhone camera roll today, I heard the stories and memories. I rolled out a map.

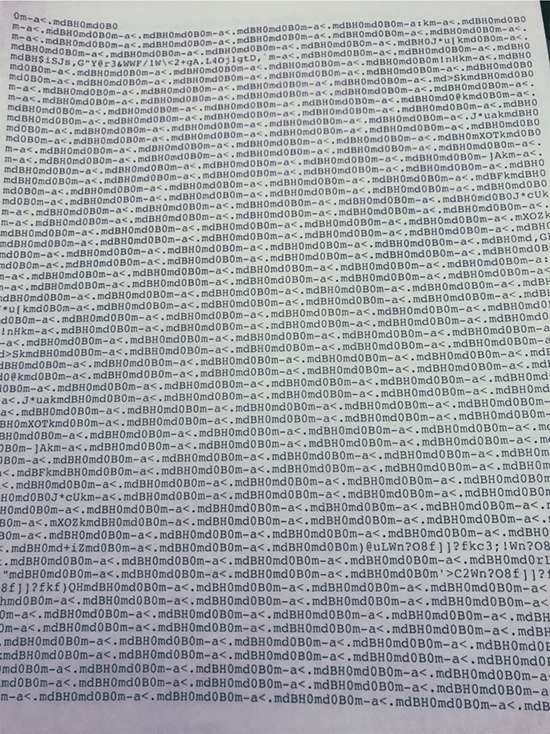

We need maps in our lives. We need patterns. We need familiarity. We need the things to repeat so as to know when things do not. The first image here is my first attempt to print my poetry manuscript for my first book. I knew I would lose the pages so I took this picture. Somehow, this entire page of coding came out instead of the poetry manuscript. I figured it was the map, the warp, the pattern of the poems. You see, the second image is of my partner warping a loom to begin weaving. It starts with the warp, its pattern, its structure, that will hold the design in place. I realized a Microsoft Word document is filled with coding that acts like a warp, pattern, structure, which will hold up the poem. Our world is no different. We can think of gravity, magnetic fields, gases, pressures, winds as the warp to our world, the pattern, the structure that holds us in place. There are small moments where we encounter this warp and these are the moments that inspire me the most, the reminder of energies, the reminder that we belong to a system, to a machination of small miracles.

The third image from my camera roll that stuck out to me is this image of Marble Canyon in Arizona. At the mouth of the Grand Canyon, one can see time in the flesh. Each layer holds time, holds story, holds a moment of the world. There one sees, again, the warp of the world, the pattern, the structure that holds us in place.

I do not assume that the universe is not revealed in urban structures. An entire city is a machine of systems, movement, energy, pressures that are hidden behind the noise and currents. A machination of small miracles. Even a building has a loom, a warp, a pattern, a structure. Each person who steps into an elevator, onto a floor, into a room carries with them a story, or what is known as live load in architecture. It can sometimes be felt when a person zooms by and a paper flutters on the corner of a desk. Now, imagine a poem too standing and daring it could withstand wind, gravity, and hold the weight of stories. Each element of a poem that steps into the poem’s elevator, line, room carries a weight, a story, a poem’s live load. It can sometimes be felt when you are forced to turn the page in a poetry collection, you feel something flutter.

It is said that they traveled by rainbow. You don’t need to know who, to where, from where, how, or for what reason. Trust in the miracle. Trust in the poem. Trust what you see in front of you. A rainbow. A small miracle.

We notice the ways the climate is changing. Pictured above is the Grand Canyon from the east rim on your way back to the Navajo Nation. My partner, my good friend, and I stopped to witness the setting sun and the canyon. We immediately noticed the smoke. A fire was burning on the north rim and I decided not to capture the plumes aching into the sky. Instead, I caught the after light, the after smoke that settled deep into time. Each rim, each lip, each cliff seemed to shush themselves as the smoke snaked down to the river. We notice these things changing but there seems to not be a way to change ourselves. The after smoke of our lives is embracing the warp, the loom, the pattern, the structure of this world. When my partner hits a snag or noticing something amiss in his rug, he mends the mistake of his design and continues. He never starts a new loom, a new warp, a new pattern, a new structure. That is not what one does. It is impossible.

I do not want to end this mapping on a darker tone. Rex Lee Jim, a Diné poet and traditional practitioner, told me once that the body is a machine. The body breathes in oxygen and transforms it to carbon dioxide. The body can change elements. So Jim said that the body can transform positive energy into negative energy and vice versa. The Earth is also a body. Laura Tohe, the current Navajo Nation Poet Laureate, said mountains have kidneys and stomachs, each one alive, full of energy. The Earth will move to mend its body, even if we are not here to witness it. One day, it will want to return to the sea, to the sun. I think we all do at some point, too. So when I am out for a walk, I see these small miracles happen, though I tend to not walk far from home as I have an unreasonable fear of the woods. I snapped this picture of this single wild flower blooming. It had just rained and I was excited for the new semester but also extremely stressed. My book was going to be released the following month and I was nervous and afraid. I kept thinking about all the worst scenarios in my head and numbering all the things I needed to complete. Then, I saw this flower, took out my phone, snapped a bunch of pictures, and continued walking. For a moment, I had forgotten about all the things, all the moving pieces, and I was reminded of the loom, the warp, the pattern, the structure of the world beneath and above me. Coming across this picture again, I was reminded again of that momentary quiet from the noise, that small moment where I could listen and see, that small miracle. I took the picture then and saved it to my camera roll. Today, I rolled it out as a map.

—

Jake Skeets is Black Streak Wood, born for Water’s Edge. He is Diné from Vanderwagen, New Mexico. He is the author of EYES BOTTLE DARK WITH A MOUTHFUL OF FLOWERS, a National Poetry Series-winning collection of poems. He holds an MFA in poetry from the Institute of American Indian Arts. Skeets is a winner of the 2018 Discovery/Boston Review Poetry Contest and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Skeets edits an online publication called CLOUDTHROAT and organizes a poetry salon and reading series called POLLENTONGUE, based in the Southwest. He is a member of Saad Bee Hózhǫ́: A Diné Writers’ Collective and currently teaches at Diné College in Tsaile, Arizona.