HEDI EL KHOLTI

— Last year I went to see Peter Hook, the bass player from Joy Division/New Order, perform their debut album Unknown Pleasures at the Henry Fonda Theatre. I was with my friend Stephanie. We got tickets without thinking too much about it. As the event drew closer, it became obvious that it was terrible idea. Still, I was hopeful that Hook and his band could somehow pull it off. Maybe he knows what he’s doing and this isn’t just a way to make some quick cash now that he’s left New Order.

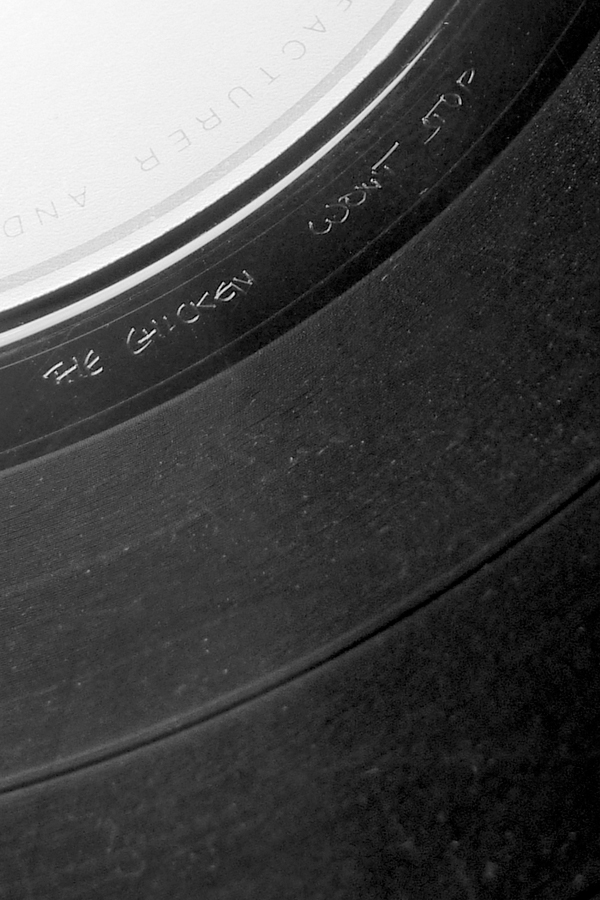

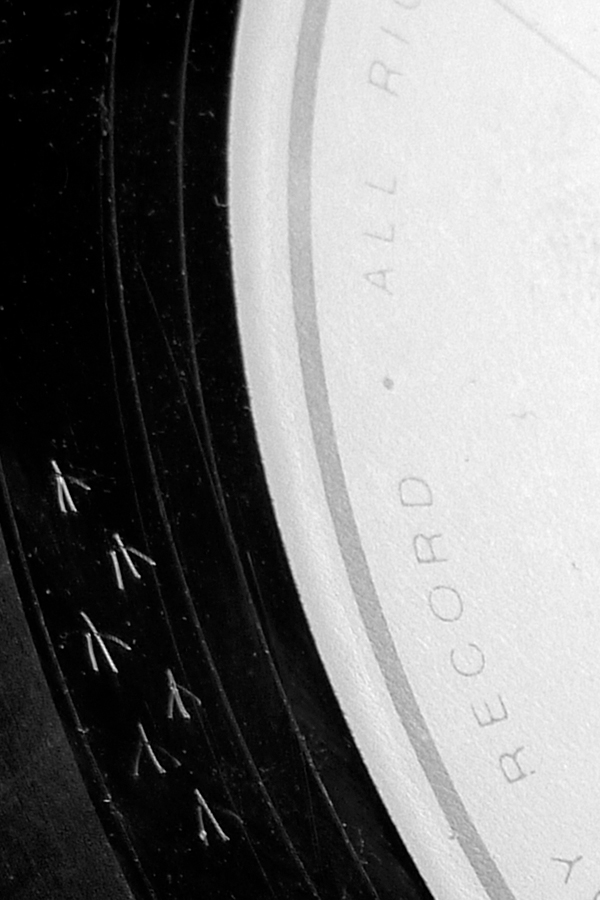

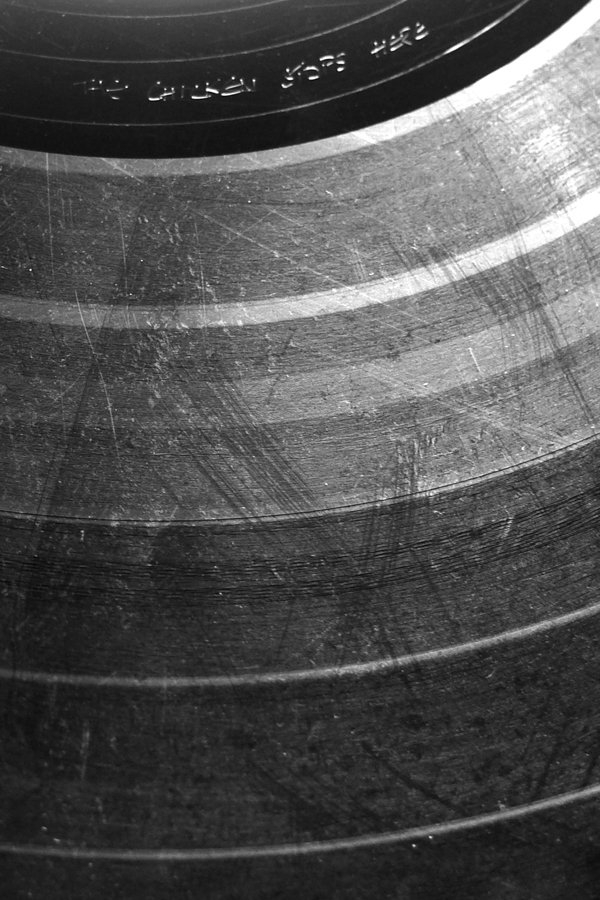

The place is packed. Old and young people, couples with kids are standing around waiting for the show to start. A transmission of knowledge. We sit at a booth and exchange trivia about Joy Division with a couple, while a documentary retracing the band’s career is projected on stage. The show finally starts and after hearing the first song, we completely lose hope. Stephanie leaves during the third song to go to our friend Heather’s Christmas party. She wants to buy a t-shirt but I convince her not to. I promise her that I’ll make her one. I think about the band’s off-grooves etchings and describe them to her. The one on Still, released after Ian Curtis’s suicide, says, “The chicken won’t stop” and “The chicken stops here.” The chicken tracks across the grooves on the opposite side would make a cool t-shirt. They reference the ending of Werner Herzog’s 1977 movie, Stroszek, where the character played by Bruno S., a street musician, leaves Berlin for the US, to escape the constant bullying his girlfriend’s ex-pimp subjects him to. After his trailer gets repossessed, and an absurd attempt to rob a bank, he ends up committing suicide. The film ends with a sequence showing a chicken dancing. Presumably this is the last movie Curtis, who was a fan of Herzog’s, saw on the BBC the night he hanged himself. All of this, and pretty much everything else, is common knowledge now, and features in the film’s Wikipedia page.

I walk upstairs to smoke a cigarette. I am vaguely hopeless but not angry as I gaze dreamily at Hollywood Boulevard. I think about what Joy Division meant to me then, what the sound signified and triggered. A floating atmosphere of defeat. Things that would unfold later, once I’d patiently deciphered the clues and researched the influences contained in the records. The two news stories I remember most from that time: the Tenerife Airport disaster in ’77, the deadliest accident in history and so close to Morocco. Jim Jones’s Guyana cult suicide on the cover of Paris Match in December ’78, a green-tinted black and white photo of bodies face-down on the ground. Leaders of men, made a promise for a new life.

An atmosphere in search of a sound. Where I grew up in Morocco, the only music we ever heard on the radio or at home was hippie music, preferably from those who had spent some time there in the ’60s—The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, Tim Buckley. Or reggae and Arabic pop music. Flashbacks of hanouts, tiny Moroccan convenience stores, plastered with posters of Bob Marley playing soccer or Bruce Lee. They both died tragically. Men out of work hanging out inside smoking and drinking mint tea. How to describe it? Shanty towns a couple of blocks from my father’s house; the poverty, Sunday weddings, a procession, donkey carts, wild dogs tortured by children, unpaved dusty roads, a pungent smell of garbage in the summer that is almost sugary and pleasant. None of it belongs to me.

The country, in economic turmoil, stopped importing goods in the late ’70s, and the record stores that remained open just kept selling their stock as if history had stopped. The first 7-inch I remember buying was Visage’s Fade to Grey during a summer vacation to France in 1980. It was a total aesthetic shock to hear that particular mix of dance music tainted by melancholia, the sound that would later be perfected by New Order, Depeche Mode, and the Pet Shop Boys. An atmosphere in search of a language. ESL, half-understood lyrics, words became triggers. The meaning was always delayed by the discrepancy between the music and the lyrics.

I remember how unhappy I was then while listening to Closer. The drum roll at the beginning of Atmosphere a secret signal, “Don’t walk away in silence.” I can’t listen to their music very much anymore. Its meaning has been emptied out. “Oldness comes to rile the youth who dream suicide,” sang the Red House Painters. I think of the last page of Pierre Guyotat’s Coma, about what replaces that space, “a heart that only pumps blood, and blood that is no longer warming.”

Hedi El Kholti is a cultural presenter who has worked with Tony Duvert, Abdellah Taïa, Gary Lee Boas, Grisiledis Real, Holy Shit and other intellectual luminaries. He is Managing Editor of Semiotext(e).