GLENN LIGON

PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG MAN

— In 1976, when I turned sixteen, I realized I was on my own. That is, I realized the world I wanted for myself was distinctly different than the world my parents wanted for me, because the world I wanted for myself included art. Now, my parents weren’t against art; in fact they saw art appreciation as part of a well-rounded education, an education they were struggling to send me to an expensive private school to get. Because they believed in the value of art they also scraped together money for me to attend pottery classes in Greenwich Village when I was ten, a neighborhood very distant from the South Bronx housing project where we lived, and, when I was older, they sent me to after-school drawing classes at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. No, it wasn’t that my parents were against art; it’s just that they didn’t understand what being an artist meant. “The only artist I’ve ever heard of,” my mother told me, a whiff of terror in her voice, “is dead.” I knew she meant Picasso, whom she had probably read about in a profile in Life magazine, but what she really meant was she didn’t know anybody making a living as an artist and she was scared about my future. Like my mom, most of my relatives were civil servants, working in the Post Office, Department of Motor Vehicles, or some other government agency. For my relatives, just one generation away from a sharecropper’s cabin in rural South Carolina, the notion that one could be an artist, much less raise a family on an artist’s salary, was foreign to them. Art was ultimately something for white folks and although my mother thought that I should know about things that white folks do (hence the pottery classes) she did not necessarily think I should emulate their behavior.

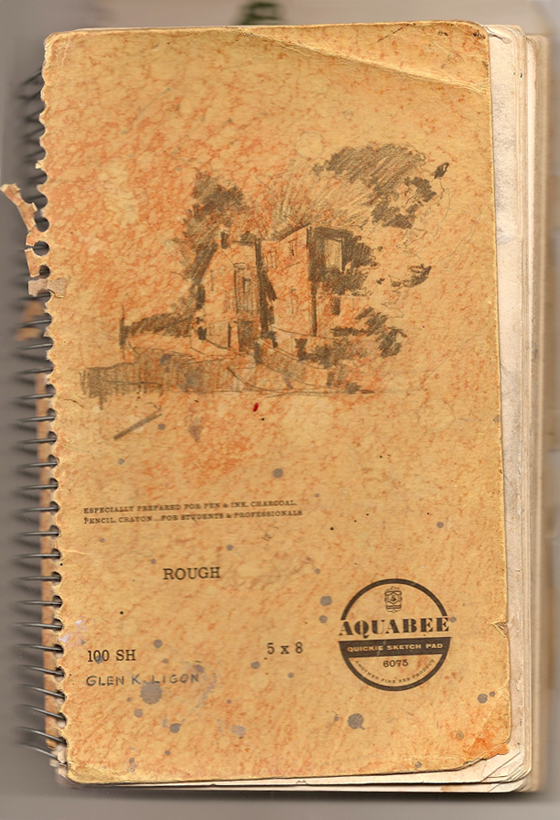

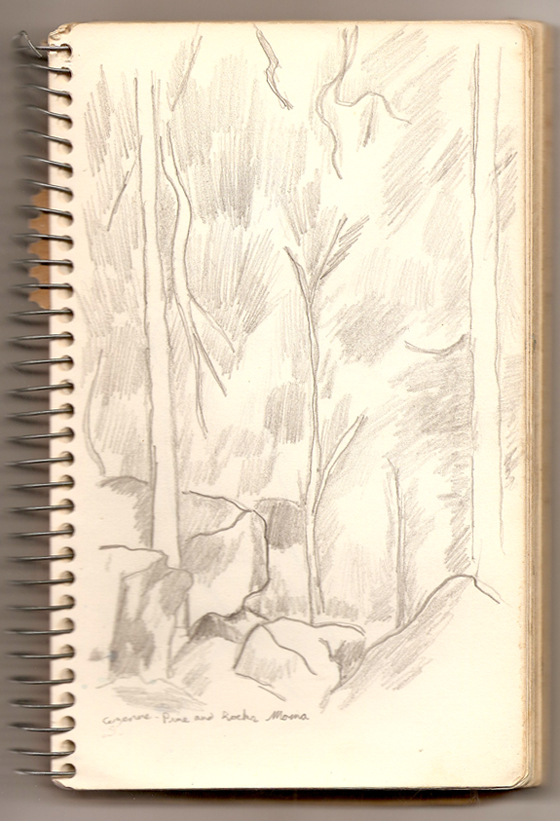

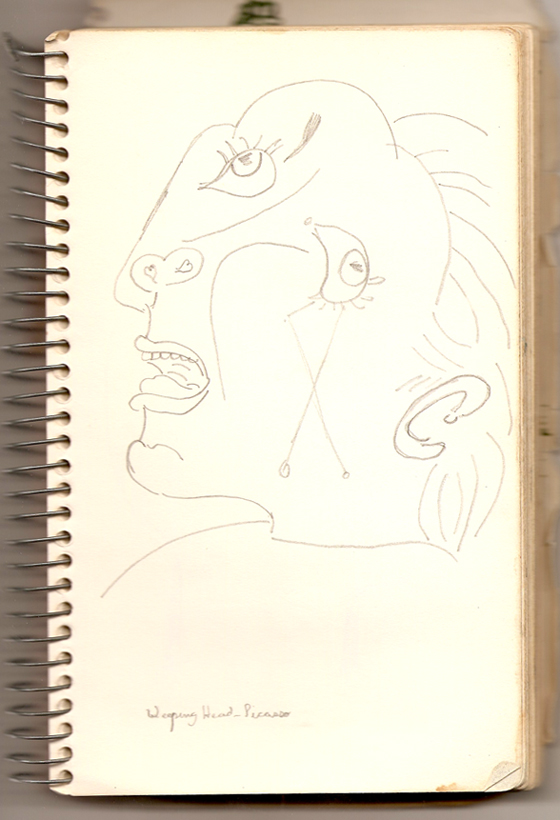

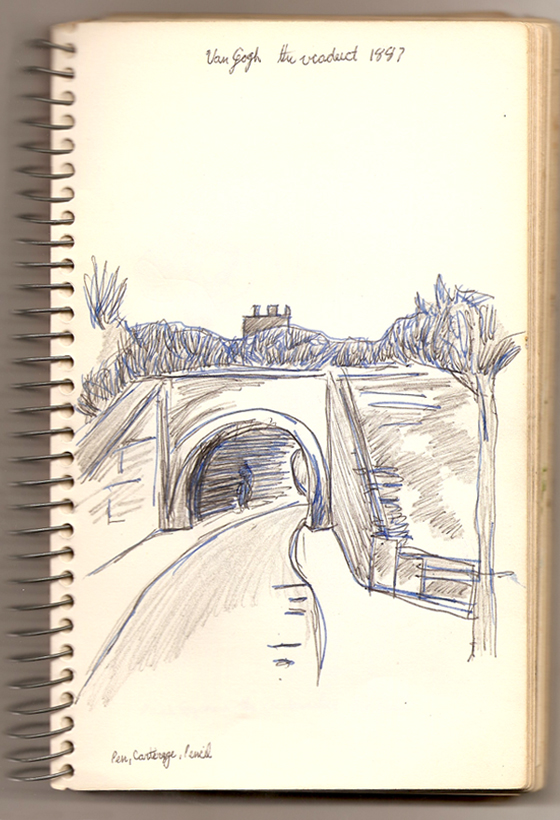

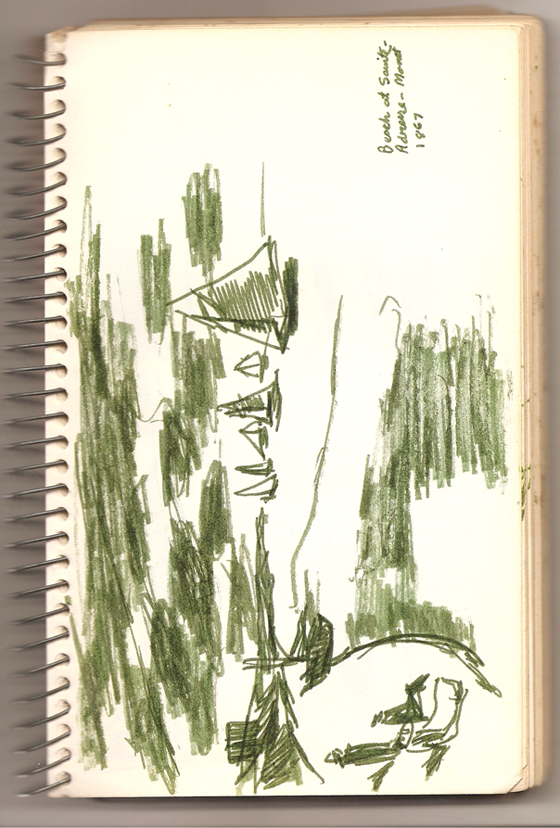

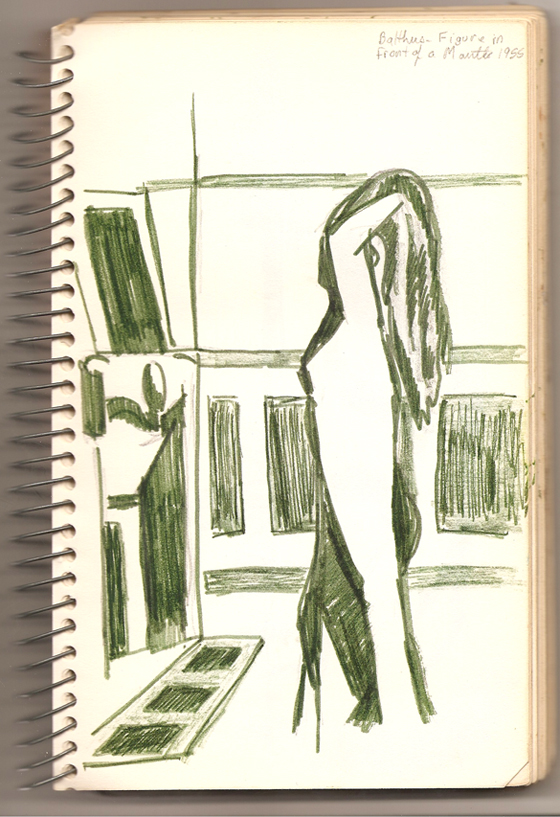

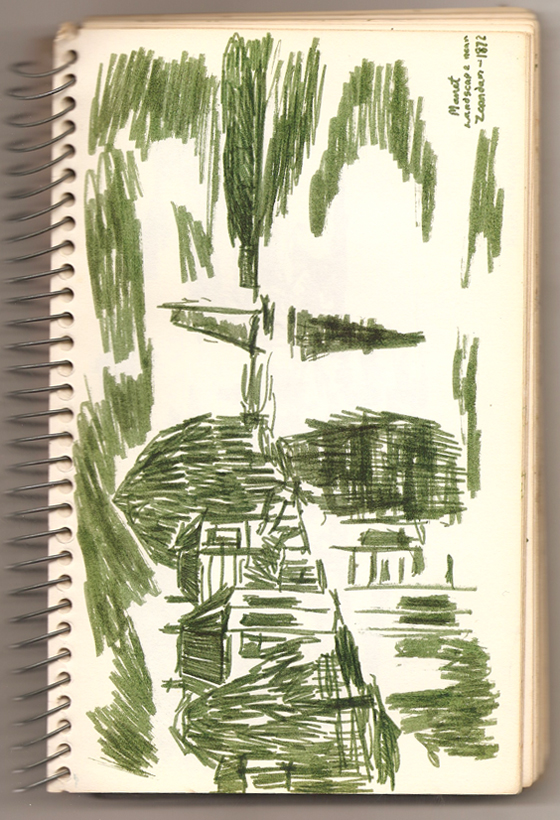

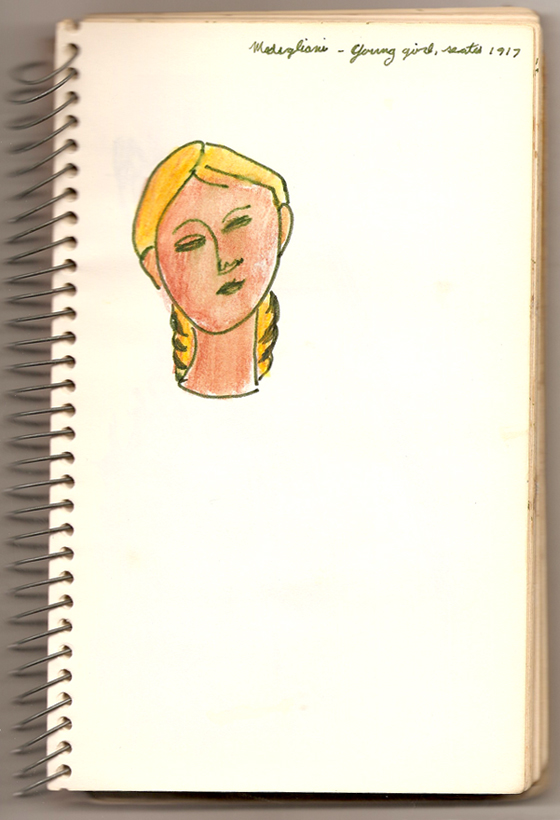

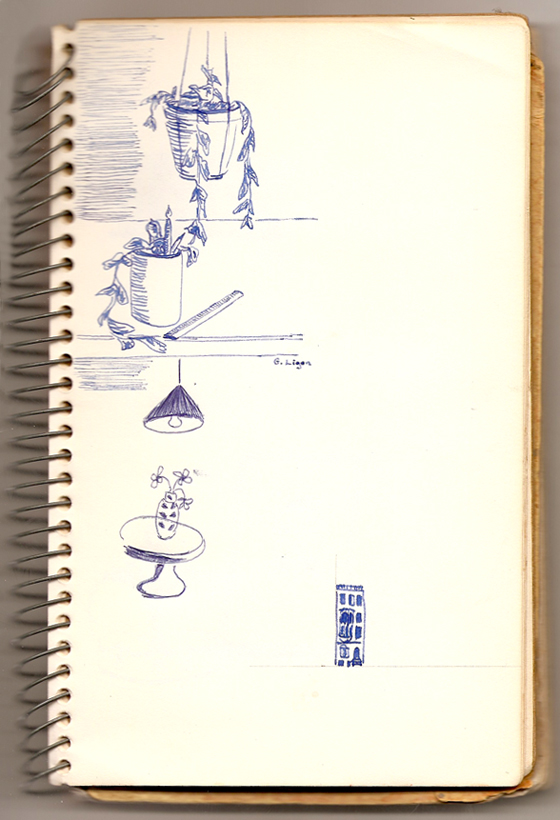

When I turned sixteen something changed. I had gotten a job as an office assistant at a social service agency, joined an extracurricular poetry workshop lead by a beloved creating writing teacher in my school, and slowly, tentatively, realized that I was attracted to other boys. These activities and revelations took me out of the South Bronx and the orbit of my family and towards a place where I could begin to imagine my life beyond the limits of my parent’s experiences and expectations. That’s the moment when I bought my sketchbook. At some point I must have been told that to learn about art you had to draw art, so I started carrying a sketchbook around to record the things I saw on trips to museums and galleries. It was a spiral-bound, five by eight inch book with an orange cover. Bizarrely, when I wrote my name on the book I spelled it wrong, as if the person I wanted to be in the sketchbook was a slightly different version of the person I was. I was enamored with French or French-identified artists and the sketchbook is full of drawings after works I saw on the walls of MoMA or the Met. Cezanne, Matisse, Picabia, Picasso, Duchamp and Modigliani were my heroes, with an odd Munch or Feininger thrown in the mix. Rendered in pencil or a now faded-to-green black magic marker, these drawings represented travel without traveling; my adolescent self imagining a world that I didn’t quite have access to but somehow knew was waiting for me. That the drawings heavily favored European modernism, non-western art being represented by one cursory sketch of an Inuit canoe prow, did not seem to be a problem at the time. Art, as my mother said, was what white people did and so that’s what I recorded in my sketchbook. Although I knew I wanted to be an artist it did not occur to me to seek out ones that looked like me. Besides, artists that looked like me were scarcely represented on the walls of major art institutions in the mid 1970s, unless it was February––black history month—when curators would grudgingly go down into the vaults to find something to stick up for a couple of weeks.

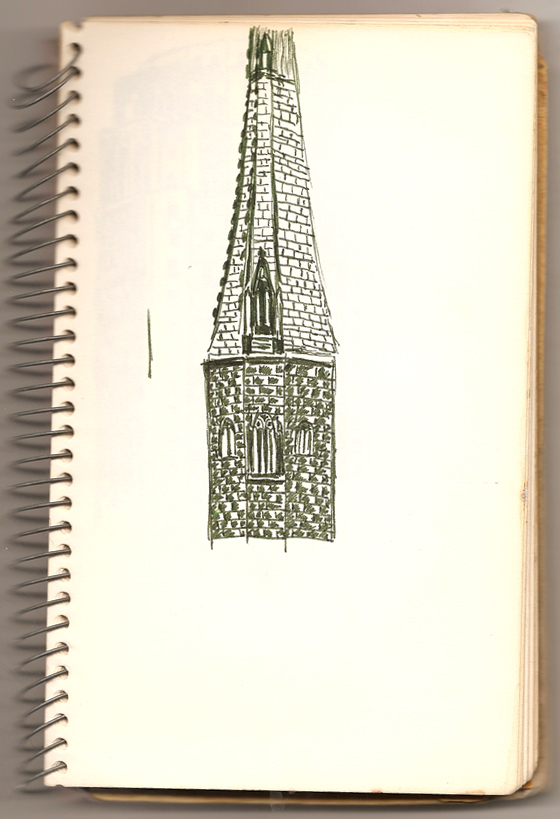

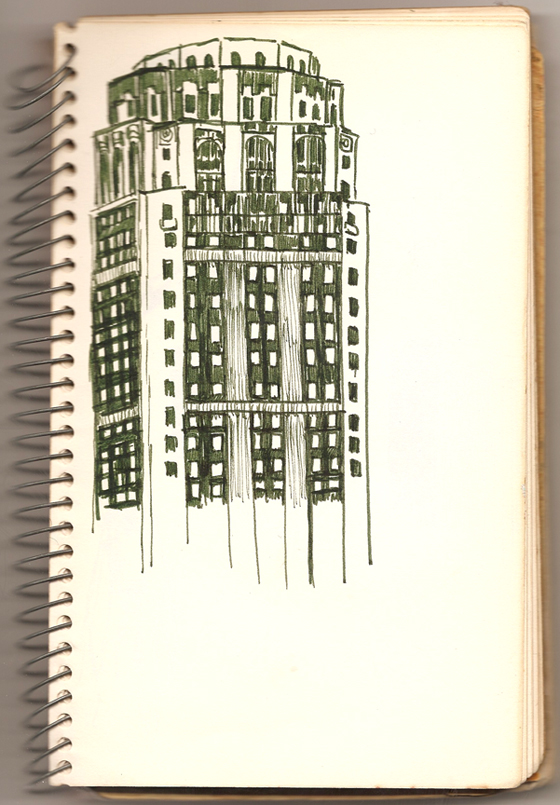

At some point I started drawing still lifes and pictures of buildings from magazines. The drawings were strange. The still lifes were clumsy and sentimental, whereas the ones of buildings and architectural fragments were graphic and bold, if not a bit obsessive; every brick on a church steeple or window in a skyscraper rendered in loving detail. By that time I had been swayed by my parents’ concern about my nascent artistic career and had begun telling them that I wanted to study architecture when I got out of high school. Although nobody in my family had studied architecture, I figured my parents would be more at ease if I told them my drawing classes, sketchbooks and trips to the museum were all toward my career goal. To be sure, I was genuinely interested in architecture, but it was merely the wig with which I covered my real desire to be an artist. I wore this wig until I graduated from college, knowing that if I had failed the undergraduate perquisites for an architecture major I could not still convincingly pretend I was headed for an architecture career. Instead, I got a job working as a proofreader in a corporate law firm, working nights and weekends so that I could paint and draw during the day. In 1989 the National Endowment for the Arts gave me a grant for excellence in drawing. It was five thousand dollars, a fortune at the time, and I decided that no matter what my parents thought if by giving me a grant the government said I was an artist then it was my job to be one..

—

Glenn Ligon was born in 1960, in the Bronx and continues to live and work in New York. He received a BA from Wesleyan University in 1982. In 1985, he participated in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Independent Study Program. Ligon has had solo shows at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. (1993), Brooklyn Museum of Art (1996), Saint Louis Art Museum (2000), the Studio Museum in Harlem (2001), Dia Center for the Arts in New York (2003), and The Power Plant in Toronto (2005), among other venues. Group shows in which he has participated include the Whitney Biennial (1991 and 1993); Biennale of Sydney (1996), Venice Biennale (1997), Kwangju Biennale (2000), Documenta 11 (2002), and Learn to Read at the Tate Modern, London (2007). He has received grants and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts (1982, 1989, and 1991), Art Matters (1990), the Joan Mitchell Foundation (1997), and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation (2003). In 2006 he was awarded the Skowhegan Medal for Painting. Upon entering office and moving into the White House, President Barack Obama installed Ligon’s 1992 Black Like Me No. 2 in his family’s private living quarters. In 2011 Ligon had a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

www.luhringaugustine.com

www.regenprojects.com

www.thomasdane.com