GEORGE CLARK [NOMINATED BY LUKE FOWLER]

“Entering a library, I am always struck by the way in which a certain vision of the world is imposed upon the reader through its categories and its order. Some categories, of course, are more evident than others.”

~ Alberto Manguel, ‘The Library at Night’, 2006

Since 2009 I have been working periodically on a film project generated from the relationship of different classification systems. Drawing from the traditions of ornithology in Hong Kong, I have returned to two locations at intervals of one year to film multiple times. In returning I’ve been attempting to remake, repeat and maybe undo what I filmed on the previous visit in order to explore the contradictory traditions of bird keeping as well as my own framing and editing tendencies. The project is still ongoing so here I have gathered together some material that I have found while doing research for this film as well from curatorial projects. The material – text, animations, images and a video interview – is connected through my exploration of the ways in which information is collected, categorized and translated in the disciplines of science, bibliography, literature and cinema.

Geoffrey Herklots came to Hong Kong in 1928 and left 20 years later. During this period he found increasing pleasure, amusement and profit in the pursuit of many branches of natural history. His interest in birds was aroused by friends in the Services and, in consequence, bird-watching became a major hobby. In 1938 he spent some time in the British Museum (Natural History department) examining hundreds of skins of birds from South-east China and in writing descriptions.

This book is based on those notes, on the articles in the ‘Hong Kong Naturalist’, on the author’s field notes – most of which survived the war – and on additional recent studies in the Museum. The book is illustrated in colour and black and white by Commander A.M. Hughes (O.B.E., R.N.). Commander Hughes served on the China Station from 1929 to 1931 and therefore has firsthand knowledge of the local birds. He is already known in the Colony for his beautiful paintings of birds reproduced in the ten volumes of the ‘Hong Kong Naturalist.’

~ G.A.C. Herklots, ‘Hong Kong Birds’, 1967

The study of natural history in China was a passionate pursuit for many colonialists during the 18th and 19th Century. The discovery and categorization of the birds by Western Ornithologists was often conducted in spare time around commitments in colonial or trade offices. Geoffrey Herklots (1902-1986) specialised in birds as well as the botany specific to Hong Kong. His work draws on the pioneering studies of J. D. D. La Touche and the seven volume ‘Handbook of the Birds of Eastern China’ (1925–1934). Despite various changes in the classification of birds since LaTouche’s work, the illustrations by A.M. Hughes and entries by Herklots utilise his numerical system to enable cross-referencing between old and new taxonomies. The pages from the book displayed here show their use of numerical and pictorial systems as means of classification.

The ornithologist Robert Swinhoe (1836 – 1877) was the first westerner to publish a list of Chinese birds in 1863 and was a dedicated sinologist. As Fa-Ti Fan argues persuasively in his recent book ‘British Naturalists in Qing China’, these pioneering naturalists were not without knowledge and respect for Chinese culture and their work would not have been possible without collaboration on a local level despite the prejudices inherent in the imperialist project. Swinhoe along with other colleagues and fellow enthusiasts suggested that the names given to birds or plants should relate to their Chinese names to allow some continuity between the local culture as well as the many Chinese studies of the natural world, that date back many centuries, and the new ‘scientific’ classifications from Europe being applied in the 18th Century. But this conscientious practice was a minority pursuit. As the Russian botanist Emil Bretschneider observed in 1881, whereas some scientists strived “to preserve in the new generic or specific names the indigenous popular appellations, where known. […] the fashion now-a-days cherished among botanists is to transform names of savants or other persons (who frequently have had nothing to do with the plant dedicated to them) into botanical names, which are often dissonant and difficult to pronounce.”

The words of the analytical language created by John Wilkins are not mere arbitrary symbols; each letter in them has a meaning, like those from the Holy Writ had for the Cabbalists. Mauthner points out that children would be able to learn this language without knowing it be artificial; afterwards, at school, they would discover it being a universal code and a secret encyclopedia.

Once we have defined Wilkins’ procedure, it is time to examine a problem which could be impossible or at least difficult to postpone: the value of this four-level table which is the base of the language. Let us consider the eighth category, the category of stones. Wilkins divides them into common (silica, gravel, schist), modics (marble, amber, coral), precious (pearl, opal), transparent (amethyst, sapphire) and insolubles (chalk, arsenic). Almost as surprising as the eighth, is the ninth category. This one reveals to us that metals can be imperfect (cinnabar, mercury), artificial (bronze, brass), recremental (filings, rust) and natural (gold, tin, copper). Beauty belongs to the sixteenth category; it is a living brood fish, an oblong one.

These ambiguities, redundancies and deficiencies remind us of those which doctor Franz Kuhn attributes to a certain Chinese encyclopedia entitled ‘Celestial Empire of Benevolent Knowledge’. In its remote pages it is written that the animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.

The Bibliographic Institute of Brussels exerts chaos too: it has divided the universe into 1000 subdivisions, from which number 262 is the pope; number 282, the Roman Catholic Church; 263, the Day of the Lord; 268 Sunday schools; 298, mormonism; and number 294, brahmanism, buddhism, shintoism and taoism. It doesn’t reject heterogene subdivisions as, for example, 179: “Cruelty towards animals. Animals protection. Duel and suicide seen through moral values. Various vices and disadvantages. Advantages and various qualities.”

I have registered the arbitrarities of Wilkins, of the unknown (or false) Chinese encyclopaedia writer and of the Bibliographic Institute of Brussels; it is clear that there is no classification of the Universe not being arbitrary and full of conjectures. The reason for this is very simple: we do not know what thing the universe is.

~ Jorge Luis Borges ‘The Analytical Language of John Wilkins’, 1942

Translated from the Spanish ‘El idioma analítico de John Wilkins’ by Lilia Graciela Vázquez.

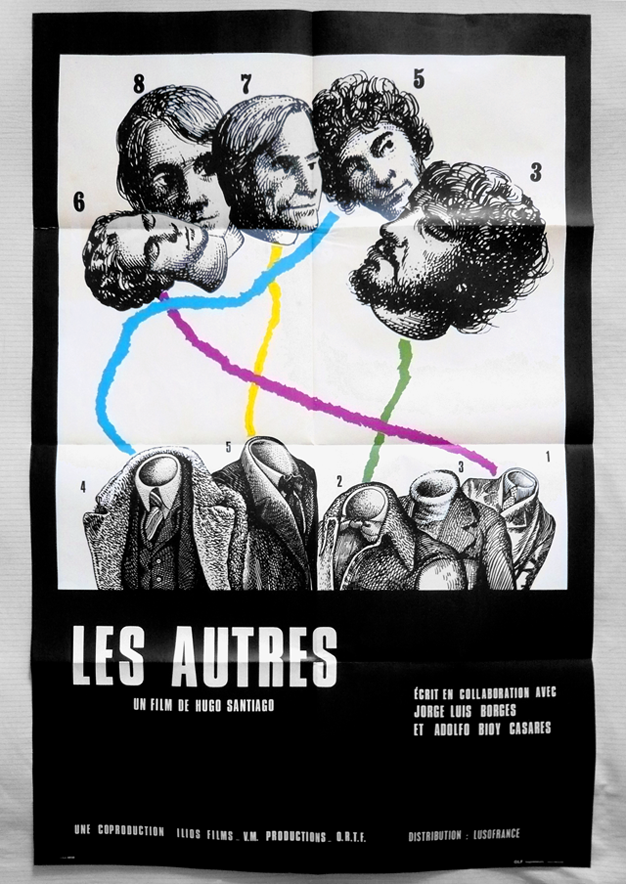

The film director Hugo Santiago (Buenos Aires, 1939 – ) made two unique feature films in collaboration with Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy-Casares. The first film Invasión / Invasion was made in Argentina in 1969 and second Les Autres/The Others was made in France in 1974. Originally from Argentina, he has been predominantly based in Paris since 1959, where he has made both fictional features and a range of essay films and documentaries on and with figures such as Maurice Blanchot and Iannis Xenakis.

The interview here focuses on his work with Borges and Bioy-Casares on these two feature films; the development and planning of Invasion and in particular the design and mapping of the fictional city of Aquilea out of fragments of Buenos Aires. The discussion of his second and lesser known film ‘Les Autres’ explores the films complex splintered narrative, his use of color as well as the films troubled premier at Cannes in 1974.

The video is a newly edited from an interview I conducted in September 2008 while I was in Paris researching Hugo Santiago’s films. The interview was conducted in French with live translation by Aubrey Richard Wanliss-Orlebar. Thanks to Chris Pencakowski for help transferring the video.

The film and its opening are the same mobile story in two modes. A son kills himself, and the father, as though unhinged, will pass through a series of metamorphoses: a sadistic small-time crook, a disturbing wise man, a nomadic walker, a young man in love. The actor who plays the father, Patrice Dally, displays a deep sobriety, an almost humble manner, which intensifies the violence of the metamorphoses. The pretext is a sort of inquiry into the son’s death. The reality is the broken chain of metamorphoses, which operates not by transformation, but by leaps and bounds.

[…]

It’s like a story planted in Paris, not at all heavy and static, but with light stabs that correspond to each camera position. The story comes from elsewhere: it comes from South America, from the Santiago-Borges-Bioy Casares ensemble, bringing with it that power of metamorphosis which one finds in the novels of Asturias, and it emanates from other landscapes: the Savannah, the pampas, a fruit company, a field of corn or rice. The precise point at which the story is inserted or stuck in Paris is a small bookstore, “The Two Americas,” the father’s business. But there is no application in the story, no symbolism, no literary game, as though an Indian story were being told in Paris. Instead, the story is precisely shared by the two worlds, a city fragment and a pampas fragment, each of which is quite mobile; the one is stuck in the other and carries it away. What appears continuous in one would be discontinuous in the other, and vice versa. I am thinking of the admirable way in which Santiago filmed the interior of the Meudon Observatory: a metallic and deserted city has been planted in a forest. The tam-tams leap from Couperin’s music, the parrots screech in the Odeon hotel, and the Parisian bookseller is truly an Indian.

Cinema has always been closer to architecture than to theatre. A particular relation of architecture and of the camera holds everything together here. The metamorphoses have nothing to do with fantasy: the camera leaps from one point to another, around an architectural whole, just as Planchon leaps around the huge stone fountain. The bookstore’s characters leap from one to the other around Valery, the heroine who knows how to strike architectural poses. Standing or bending, leaning or upright, she watches the metamorphoses from Meudon; she is at once the victim and the instigator of the game; she is the center for the bookseller’s leaps. Actrice Noelle Chatelet: what talent and beauty, what strange “gravity” in the detailed love scene. What about the way in which she, too, though differently than the bookseller, maintains her relationship with the other world? What she says in architecture, in her look, and in her position, he says in movements, in music, and in the camera. It is strange that the critics didn’t care for this film, even if it were only an experiment in cinema endowed with a new mobility. Santiago’s previous film, Invasion, was already moving in this direction. (The tiebreaker: why is the bookseller named Spinoza? Maybe because the two Americas, the two worlds, the city and the pampas, are like two attributes of an absolutely shared substance. And this has nothing to do with philosophy, it is the substance of the film itself.)

~ Gilles Deleuze, ‘A Planter’s Art’, 1974

From Desert Islands and Other Texts 1953-1974

Edited by David Lapoujade, Translated by Michael Taormina,

SEMIOTEXT(E) FOREIGN AGENTS SERIES, 2004

—

George Clark is a writer, curator and artist. He recently worked with Luke Fowler on the film THE POOR STOCKINGER, THE LUDDITE CROPPER AND THE DELUDED FOLLOWERS OF JOANNA SOUTHCOTT (2012) based on the experiences of Marxist historian E.P. Thompson in West Yorkshire from 1946 – 1965. Together with Beatrice Gibson he co-wrote the script for her film THE FUTURE’S GETTING OLD LIKE THE REST OF US (2010). He was one of the curators of the 6th Bangkok Experimental Film Festival (2012) and curated the Lav Diaz focus at the AV Festival (2012). Other curatorial projects include INFERMENTAL for Focal Point Gallery (2010) with Dan Kidner & James Richards and NO WAVE: NEW YORK 1976-1982 (Glasgow Film Festival, Worm, Rotterdam & Cinéma Nova, Brussels, 2011). Together with Dan Kidner and James Richards he edited the new book A DETOUR AROUND INFERMENTAL (2012).