FRANK MOSLEY

— He said to listen to the environment. The he being the master filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami, all of us leaned forward in unison on creaking seats and clung to every word that he spoke. I tried desperately to jot down bits and pieces, to grasp hold of his words even in the near dark of the auditorium.

In less than six months’ time, the words that issued from his lips would take on a fleeting, smoky quality, and our beloved mentor Abbas would be dead. And yet the time spent in San Antonio de los Banos, Cuba, doesn’t make me feel that such words should be just so ephemeral.

Even today, talking to the workshop’s other forty-nine participants whom I now called dear friends, catching up on the phone, bumping into another on a NYC street corner, we all play the part of detective. An array of anecdotes and lessons had burrowed into us all, accompanied us to our homes, our beds, our respective countries, absorbed in blood to mull over, dream, ponder, and process. All tenuous. All fragments. For me, it was when Abbas said: “Do not dictate the story to your environment. Let your environment speak to you. Let it tell you the story. It will be more real, more authentic, more genuine.”

My notebook from the near dark of that auditorium shows the violent scrawls of a hand impassioned. Possessed.

Words were important here.

After all, it was no coincidence that the film school hosting our ten day workshop, the Escuela Internacionales de Cine y Tv (EICTV), was founded by the novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez—-a friend of Abbas and apparently a devoted cinephile. Words themselves adorned the school walls, parting messages spray-painted by all the mentors who had come and gone, the Coppolas, the Jarmuschs, the Hupperts. The words surrounded us daily as we stumbled to the cafeteria for coffee at dawn, haggard and bleary-eyed, as we raced the halls to beat the light to get that last shot.

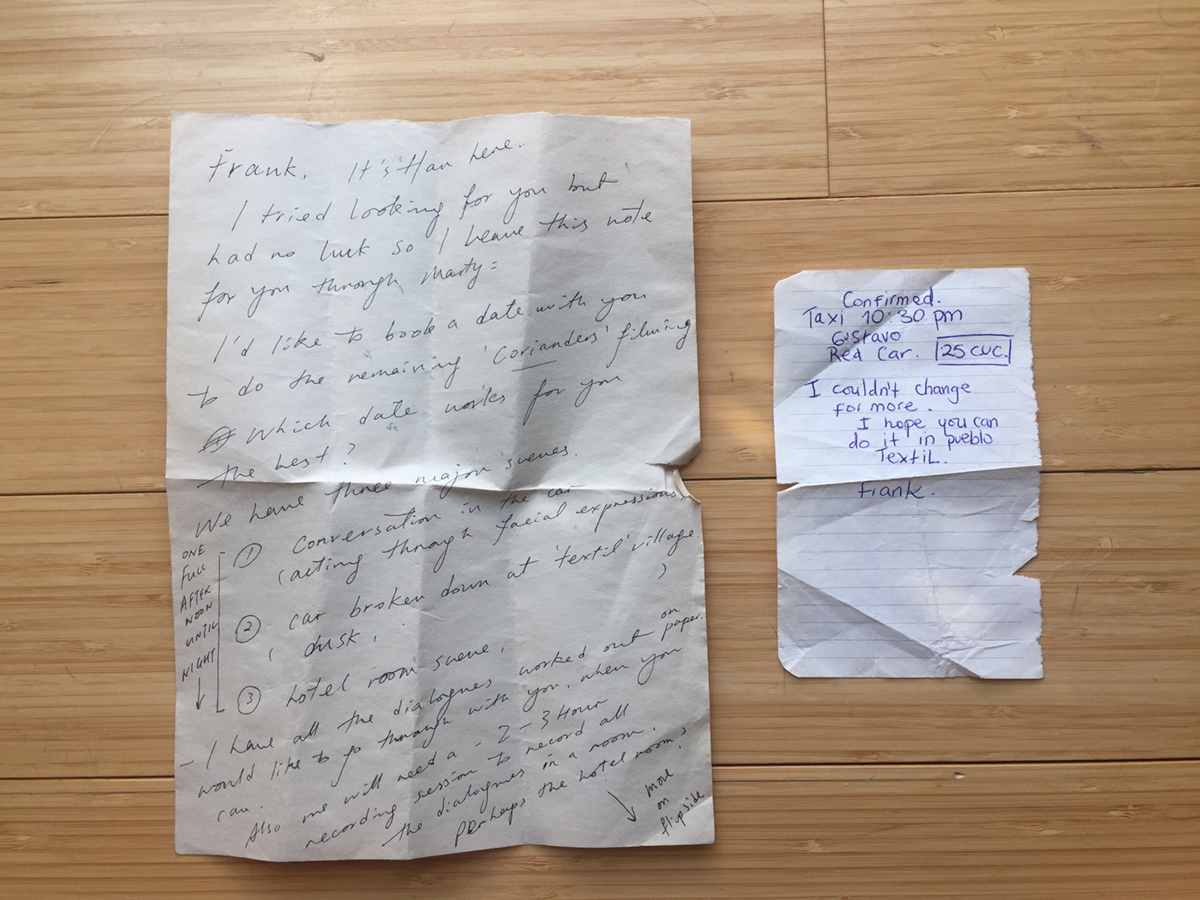

There was no cell reception for us. No texting. So we left notes for another. We learned to use our hands again. We slipped them under doors, wedged between jamb and rusty knob, entrusted the words themselves to be passed to a friend when we could not find pencil and paper. Our own little oral histories.

I remember having to pitch my idea to a stranger, a beautiful middle-aged woman, with the hopes that she would be the lead in my film. I had no idea who she was. Or if she was even talented. We had simply to trust one another. The only problem was that I couldn’t speak Spanish.

Thankfully, my producer Cameron Bruce Nelson could.

He graciously mimicked my energy, retained my inflection as I hit the main story beats. And yet her eyes remained locked on me, never straying from my face, staring at me through the swirling steam of complimentary school coffee. Cameron gesticulated wildly, ever the earnest translator, even as her face remained stoic and cold. Impenetrable. Then the story was suddenly over. For a moment, I knew we had failed. Either she had not understood, or she simply wasn’t interested. Her face had not changed.

She gingerly leaned forward, and then with both hands, took me by the face and kissed me softly, tenderly on the lips. She leaned back, my face still in her hands, and gazed at me with tears welling in her eyes. Then she spoke aloud for the first time that whole pitch. A pause.

“She said she’ll do it,” Cameron mumbled.

My film Casa De Mi Madre is about the very nature of words. Of storytelling and its consequences. A woman bribes a small boy, new to the neighborhood, to come into her apartment so that she can tell him all the things she wished she could’ve said to her son before he perished in a fire.

The film hinges on a single, unbroken shot of the woman using this bewildered child as a surrogate—her emotions swinging in grief from anger to sorrow. And much like the boy who is a conduit for the woman’s dead son, Ms. Carmen Rodriguez —the enthusiastic and talented actress from Havana —was the conduit for my story that night. Her performance was tremendous, and I will forever be grateful for her vulnerability and courage.

I gave her my heart on paper. In turn, she gave me her heart onscreen.

Words were translated from English to Spanish and back, all through the night. It became as much a film about struggling to find the right words in grief as it was a film about a group of sweaty people all trying to effectively communicate within a small, cramped apartment. There is the old saying from Godard that every fictional film is a documentary of its actors. Rivette later expanded the aphorism, saying every film is a documentary of its own making. This is exactly what the film is to me.

|

|

The child who appears in our film—Christian Jaime—wasn’t an actor. He was a local boy with a trademark grin who’d frequently shadow the filmmakers through the neighborhood, often offering to help carry sound gear or camera equipment. I gathered by the end of the shoot that we might’ve rubbed off on him because you’d be hard pressed not to find him off in a corner, looking through one of our cameras. And when you’d try to pry it out of his curious little hands, he’d usually spin the camera around and begin directing us himself.

He would always speak to me in a hushed tone that was quietly conversational, even conspiratorial, as if we were old friends. Always posing questions he knew that I couldn’t answer in Spanish. And yet we talked regardless. In two separate languages. Still connecting. I think he knew I liked it.

There was a moment when I was describing the bribe the woman uses to lure the oblivious child to her living room. In my script, the bribe was money. Carmen and our tireless on-set translator Yaite Luque immediately glanced at one another and broke into knowing laughter. I was baffled. Carmen gently explained to me that it was a very American thing to use as a bribe — money. I asked them what they thought a good replacement might be. And their suggestion was something far more haunting and innocent than a few wrinkled bills could’ve ever been.

One of the last shots of the film is of an abandoned chocolate ice cream, melting languidly across the tabletop as we hear the offscreen weeping of a lonely mother.

Abbas said to listen to the environment. So I learned to listen.

And I’m still listening.

—

Frank Mosley is an actor and filmmaker from Texas. He has participated in the 2015 Berlinale Talents, 2017 NYFF Artist Academy, and Black Factory Cinema’s 2016 Auteur Workshop, led by the late Abbas Kiarostami in San Antonio de los Banos, Cuba. His performances have been seen at Cannes, Sundance, Berlin, SXSW, New Directors/New Films, AFI, Viennale, BAMcinemafest, Slamdance, and much of his directing work has been exhibited on Fandor, MUBI, and Filmmaker Magazine. He’s been called “a superb actor and filmmaker” (RogerEbert.com), “an indie hard-hitter” (The Playlist), and “the sort of experimentalist we don’t see often enough” (Keyframe).