AMRA BROOKS

— An ex of mine once made a snarky comment about how nostalgic I was, how my writing seemed perhaps overly preoccupied with the past in a way that glorified it. I don’t think nostalgic is quite right. I don’t long for the childhood I lived; I long for the one that could have been. One that was parallel. It’s like if I could go back to that time and have my adult self there as my guide to let me know that I made it out, then maybe I could have had more freedom to be a kid.

Recently I was given some photos of myself as a child that I had never seen before from different times in my life. Some with my parents. Some by myself. Some with other children whose names I no longer know. Some are pictures of when my parents were still together before I was two- a time I don’t remember except for blurry sensory details of tree stumps, the taste of snow peas picked from the vine, and the feel of my mother’s skirt.

These photos were in a box of my father’s things that someone else had for many years. That person died. My father got the box.

Maybe this person didn’t have to die for me to get these photos. But I won’t deny that there could be something literary in that.

Maybe there was something else that could have happened?

Maybe if my father hadn’t left the box with them in the house we all used to all live in, I’d have known more of myself in those years. But a photo from the past doesn’t mean what it does now without the context of the present.

I spent the better part of this year in therapy uncovering some of my time in that house with my father and the person who had these photos and who has now died, and the situation that led me to live with them. Somehow, it’s harder to write about them now that they are no longer here. Hard especially because they didn’t like when I had written about them before. Hard because for the past 15 years I had not been able to talk to them for reasons I do not wish to write about here. Hard because there have been many therapists and many years of trying to feel safe.

I have no desire to address the dead out of disrespect, but I’d like it to be known that I saw their pain, and all the ways they were undone by circumstance. My father reminded me when I was a child and stung by their lashing out. I held their narrative, it gave a reason for what felt unreasonable. This made it hard to lay claim to my own wounds or create a context in which to live. I felt invisible, without circumstance or context.

These photos, new to me, showed me things I had never seen.

On the back of a third-grade picture there is an inscription “with love” in my crude but careful letters.

A photo of me in a cloth diaper and white under shirt next to a wooden farm fence standing in tall golden grass and a sunflower bending above me, maybe 18 months old. An age I had treasured in my own son not long ago- while looking, he asks, “What I am doing here, Mama?”

“That’s me,” I replied, my heart warmed by the connection between our selves. And happy he sees himself in me despite everyone saying he and his dad are twins.

Another pic of my mom holding me, faded in color, magentas and warm pink hues taking over, a cigarette in one of her hand, me in the other, leaning against a car. Some of my dad in denim cutoffs holding my hand as I toddle.

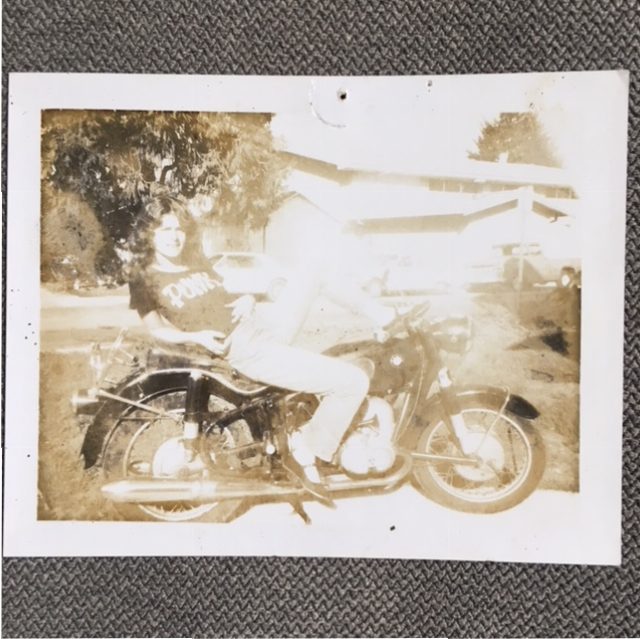

My mother in jeans and mary janes and a Punk Magazine tee shirt on a motorcycle before I was born. A thumbtack hole from where my dad said he had it pinned on his wall.

Their friends in long scarves, billowing hair and sleeves, hats, denim. Faded golden pink or black and white- the stark sun shining.

My parents were just babies when they became parents. The same age as some of my students. Their brains still developing. In most all of the pictures there are adults, the child-parents posing, the real child prop like, or off to the side. I would have also made terrible decisions if I had been a parent at that age.

Who were we all before we were broken?

I tell myself there was a time, a small window, where I was just a child. And in that window, there are tea roses and nasturtium, redwood trees, foggy beaches with freezing water, naked baby dolls, acrylic knits from my grandmother and long homemade skirts, polyester pants form the goodwill, sensible shoes, red rubber boots, a mother with braids who baked bread, too soft fruit and my face sticky with jam. There are times when the sunlight was warm and would stream in through the window and I would go underneath a pink and white bedspread while napping in my underwear and see a quiet warm and rosy place.

But that space was a safe one that I found when I was old enough to already know that my body felt unsafe and full of worry outside of that blanket.

There is also a time, when I was eleven, that I was more than just my circumstance or context. I can see it in my face in these discovered photos of me in oversized 80s tee shirts, playing dress up in a blue gown, a towel after exiting a pool. My school picture from that year, in a green and black plaid flannel buttoned all the way up, bangs covering my eyebrows. The photos showing me that I was there all along, even if no one else saw me. It has been hard going, talking about this time in particular with this newish therapist. Times it’s taken me down onto the carpeted floor in his office. Times where I had to grip his hand tightly until I was back in my present body and sit in a ball in the next room while he saw another client until I was able to stand, walk, drive, then pick up my own child and mother.

Context and circumstance is not something I can dip easily back into. The time and place in that house where the photos were left was something I never wanted to return to. I spent years there waiting for something better to come.

And now here I am. 44. A mother of a five-year-old. A professor. Across the country from California where I began and grew up. In Rhode Island in a house I own with my husband. We have a garden that only grows small stunted vegetables and wild perennials that the previous owner planted and I appreciate. I write things that I try to finish. This over simplifies the present of course.

I’m afraid of dying all the time.

I want to be here.

I wonder if it’s possible that I am old enough or conscious enough so that my child won’t have to hold my circumstance or my traumatic experiences. I hope that I am not so undone that he will be free of having to understand the root of my pain. I’m hoping to get there. To give him the freedom my body mourns.

These pictures, the ones that allowed me to see myself, well I couldn’t find them for a couple weeks. I searched the house and they seemed to have disappeared, which somehow made sense and seemed to be part of writing this.

And then I found them and put them in an envelope, not looking at them again until I was finished writing.

Knowing that while remembering my brain will make up a new part each time with or without the photos. Memory is unreliable, but our bodies keep accurate records. The memory my body holds is more trustworthy than the pictures my brain creates and the stories that go along with them.

When I looked at the photographs, the first time, I could see me. A connection between the past and the present. One that I couldn’t quite see before because she, that child me, was stuck in that time and place, locked into her circumstance. And for reasons, having to do with time and space today, maybe she’s not now. Maybe she’s a little more free.

—

Amra Brooks’ novella CALIFORNIA was published by Teenage Teardrops in 2008. In addition, she writes critical essays and reviews about contemporary art, poetry, and creative nonfiction. Her writing has appeared in Artforum, Inventory, Printeresting, Ping Pong: A Literary Journal of the Henry Miller Library, Entropy, Spin Magazine, index, the LA Weekly, The Encyclopedia Project, and many other publications. She has taught at the University of California in Santa Cruz and San Diego, Naropa University, and Muhlenberg College. Currently she lives in Providence, Rhode Island and directs the creative writing program at Stonehill College in Easton, MA where she is an associate professor. She is working on a book of creative nonfiction called BREATHING ASTEROIDS.