SCOTT KING

“I did like them … I do like them, but … well…”

“Well, what?”

“Well… it’s just that last year, when you started calling them The New Way… and said you were only going to paint pallets from now on… I got a bit… apprehensive.”

“Oh.”

“Sorry.”

— This was the anti-climax to a few months of vague planning. My friend Jake has a gallery, and early last year I emailed him some photographs of a wooden pallet that I’d painted. He got quite excited about it and we started to talk about doing a show of painted pallets – nothing untoward, maybe me and another artist in a small show at his gallery, we’d work out the logistics with Herald St.

I hadn’t just sent the pictures to Jake. Fishing for expertise and justification, I’d sent them to a lot of people; curators, writers, critics and my own galleries … and a museum; but there was little or no interest. Neville said he liked them, but offered no more than that. Most people just didn’t reply; a clear sign that they thought the painted pallet was terrible. Nicky at Herald St ignored me until I pressed him for an answer. Finally he emailed me back; ‘What do the colours mean? Do they represent something? Is there a system? ’ The email ended ‘Why did you do this? x.’

At the start of 2009 I was in a slump; 2008 had looked so promising but had ended in disappointment. As I sat looking out at the snow from my studio/dining room in January 2009, I wished I could be anywhere else, doing anything else. I needed to find The New Way, I needed to break the ‘idea/computer/printer/show/gallery/storage’ axis. I needed to make work that I could engage with; physical, real work, because The Old Way wasn’t working.

So, I started making mobiles out of scraps of wood that I’d found around the house. Brightly coloured mobiles adorned with stenciled fragments of conversation. But the mobiles were crap. Eventually, the only wood left in the house was a pallet that our new washing machine had just arrived on. Wooden pallets … of course!

I started to think about pallets: The pallet is kind of ‘ready-made’, but it’s also an essential part of the ‘business’ of art. It’s the workhorse of the gallery system and of almost every other form of shopping. All supermarket products arrive on pallets from a warehouse; in fact almost all consumer goods of any kind arrive at their ‘release point’ at the shop, on a pallet. The pallet is the last contact these goods have in the world as a ‘unit’ before they are re-presented as ‘brands’. The pallet is the mule of capitalism!

It was simple – I’d just paint pallets in the fluorescent colours that I’d been using for my mobiles. No words needed, no crude stenciled lettering – just the pallet and the paint. But – did I really need to paint them? I knew immediately that a ‘cooler artist’ wouldn’t bother to paint the pallets. A cooler artist would just declare the pallet to be the artwork. I thought about this a lot. A better artist would work on a theory of the pallets’ role in consumer society, thinking carefully about the pallet’s link with the transportation of artworks and the transportation of soap powder boxes, tumble driers or piles of freshly boxed Miu Miu shoes. This artist would just show the ‘raw pallet’. I knew that. But I thought ‘Fuck it. I must paint something. I must engage! I’m sick of their conceptual reasoning and kowtowing to art history. SOMEONE, SOMEWHERE at SOME TIME must have just made ART without knowing why – without fucking tactics – without making ART ABOUT ART. AND FUCK THEIR THEORIES! AND FUCK FUCKING CRITICS AND FUCK FUCKING INTELLECTUAL ART PARASITES! … BRING BACK POL POT AND CLEMENT GREENBERG.

It was a bright, freezing cold morning as I scoured the snow covered streets for discarded pallets. I had one, but needed more. I needed a convincing set. I didn’t need to buy overalls, rigger boots and a woolly hat to do this, I’ll admit, but I did anyway. It was the right thing to do – Robert Rauschenberg stalking stuffed goats on the Lower East Side, Manhattan, 1959.

It took me all day to find eleven pallets, and it’d been dark for three hours when I brought the last one into the house. I carried them home one by one – backbreaking real work. The hallway and kitchen were now lined with pallets – I thought about Fordism and factory work, but the BIG idea was doing it, don’t get distracted by thinking. On the second day, I got up at 7am and began dismantling the first pallet with a claw hammer. After complaints from a neighbor, I was forced to work in the back garden. A cigarette clasped between my teeth, tools hanging from my overalls pocket. I started to sweat under my woolly hat. My breath made steam train clouds in the freezing air as I ripped the pallet to pieces – smoking and sweating – Jackson Pollock, overlooking Accabonac Creek, Long Island, New York, 1948.

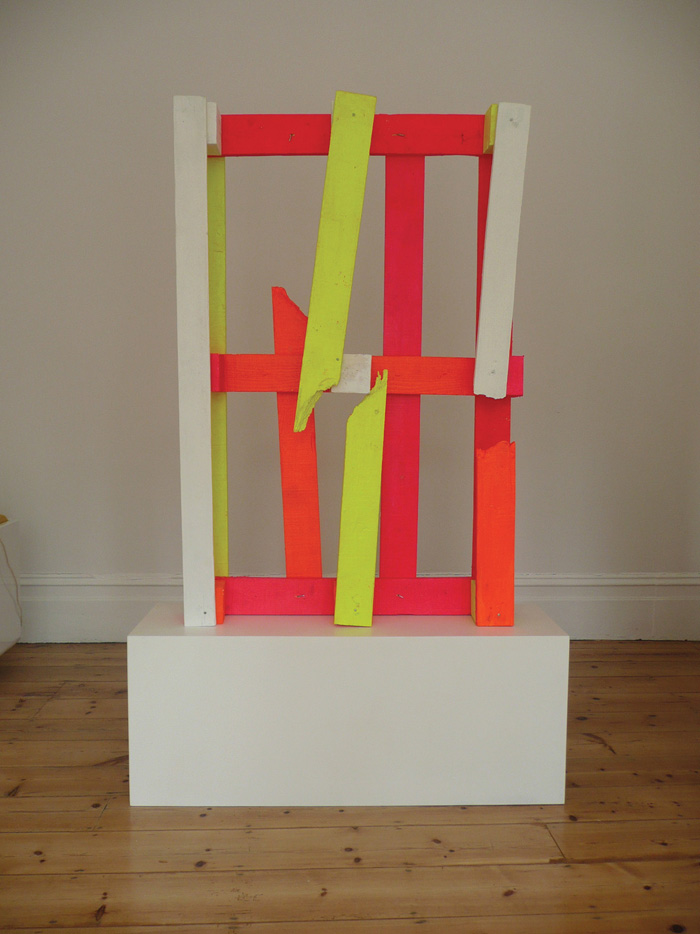

Once I’d broken the first pallet down to all its component parts, I took the bits back into my studio/dining room. I sanded all the rough edges off by hand: proper hard work. As I worked I forgot about what I was doing, just doing was enough. I did not want to be distracted by logic. I was determined not to Google in search of explanation. I kept trying out names in my head for the genre I was inventing ‘Industrial Decoration’, ‘Post-Industrial Minimalism’, ‘Fuck Off Conceptual Art Groupie Archeologist Wankers’. It was bliss. One day turned into four days as I sanded, primed, painted and varnished. The first pallet would perhaps be called Pallet #1, a nod to Jack, “Numbers are neutral. They make people look at a picture for what it is – pure painting.”

Finally, on the fifth day, I assembled the pallet. If I studied the nail holes, I could figure out exactly how to put everything back in it’s original place. Bingo! That’s all I’d done – spent 4 days in real work heaven, only to reassemble the pallet exactly as it was, albeit in different colours. The futility of this excited me. Someone, somewhere would recognize the parallels between pallet reassembly and painting, Pollock and Ikea… perhaps ‘Point #1’ in the Industrial Decoration Manifesto: Re-paint the inane.

I had to wait a week for a plinth to be built. Annoying, but it did give me time to finish 4 more pallets. The plinth was essential. Some rule of Minimalism would no doubt dictate that I didn’t need a plinth, that the pallet should be shown on the floor… maybe unpainted; a different mindset. I emptied out our living room and carefully placed the plinth in at one end, as near as I could get to a gallery setting. I cut the bubble wrap from the finished pallet and gently lifted it on to the plinth. With great excitement, I sat down on the sofa and stared at the pallet.

THE NEW WAY

2009

wood, nails, acrylic paint

110 x 90 x 12 cm

—

Scott King was born in Yorkshire, England, in 1969. He currently lives and works in London. He worked as art director of i-D and as creative director of Sleazenation magazines. Occasionally he produces work under the banner CRASH! with writer and historian Matt Worley. King’s work has been exhibited widely in London, New York and European galleries including the ICA, KW Berlin, Portikus, White Columns, Kunstverein Munich and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. ART WORKS, King’s first monograph, was recently published by JRP|Ringier, Zurich.

www.scottking.co.ukwww.heraldst.comwww.bortolamigallery.comwww.soniarosso.com