COLLIER SCHORR

— I was talking to a friend about a scene in Full Metal Jacket and he said “that is my favourite war movie”. Later, I thought, what does that mean? What does a favourite war movie satisfy? What makes it so desirable? All narrative cinema pivots on the transformation of a protagonist and so most war movies satisfy this requirement in spades. From An Officer and a Gentleman to Platoon, the young soldier is transformed into a man, either ruined by brutality or recused by structure, there is a simple pleasure in watching someone (other than oneself) abused into a potential killing machine.

The movie that influenced my earlier work was Sam Peckinpah’s Cross of Iron. A very violent, almost balletic film, Cross of Iron pits Russians against Germans in a blood sport of WWII. Without the Americans and without the Jews, this was the first war movie where there were no good guys or bad guys. Just a bunch of men in uniforms shooting, stabbing, raping, beheading. There was no transformation that I remember, only my own suspended sense of allegiance and the relief of not being represented in the film.

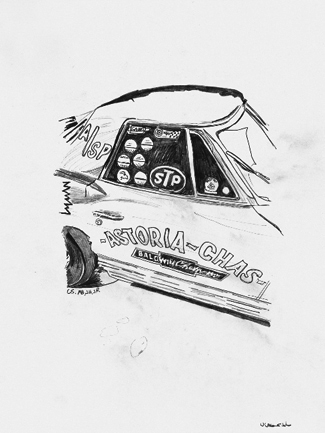

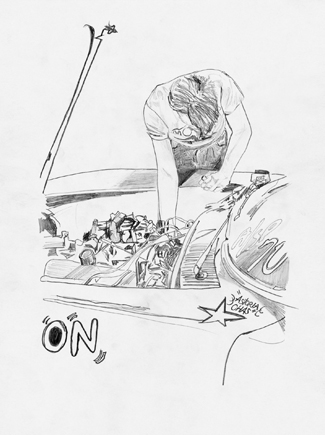

When I starting making drawing’s based on a young friend of my father’s who was killed after just on month of serving in Vietnam, I re-engaged with all those Vietnam movies I thought I loved and I no longer could love them. The fact that they were a fetish for me, and an ideal about masculinity that I couldn’t afford to indulge. My father’s friend was named Charlie and he was a race car driver, so he was already fully engaged in the fantasy of adventure and death defying acts. He wanted to get his tour of duty over as quick as possible so he could go back to Queens and continue racing his Corvette. I met him when I was four years old, when my Dad, who was an automotive photographer took me to a track in Long Island. Charlie looked like a movie star. But most of my Dad’s pictures were of the car, because at that point he was just a kid and the 67 Vette was more important than he was. Then he died and the car was raced by his friends for a year until it broke the track speed record. The winning times were written on the back window and Charlie’s sister put the car in her garage for over 30 years. It became the holy grail of muscle cars. There is no happy end to such a story. Just a lot of bullshit letters from low level military officials explaining how Charlie died. There was a cover-up and all the things we have come to believe, about casualties, friendly fire and missing paperwork seem like any number of future war movies about Iraq and Afghanistan. Like I said, there is no happy end to the story.

—

Collier Schorr is an artist and photographer. Her work explores issues of adolescence, sexuality, national identity and the body. Her photographs have been exhibited at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Jewish Museum in New York and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

She currently lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

Images courtesy of www.303gallery.com

www.artandcommerce.com

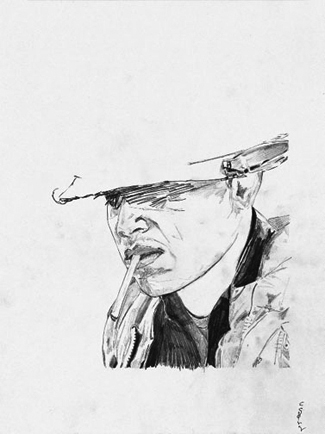

Collier Schorr, PURPLE LZ SMOKE, 2007

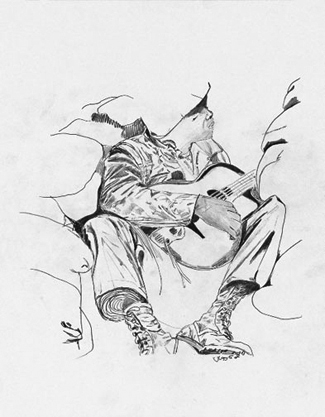

Collier Schorr, STRUMMER, 2007

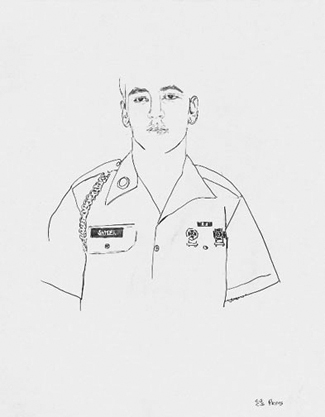

Collier Schorr, LEAVING HOME, 2007

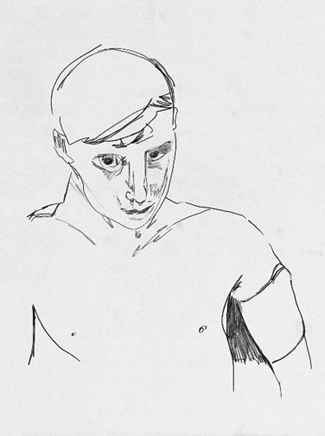

Collier Schorr, FRAGMENT, 2007

Collier Schorr, STING RAY, 2007

Collier Schorr, CHAS POSING FOR MY DAD, 2007